Minnehaha 3-year-old takes developmental changes in stride

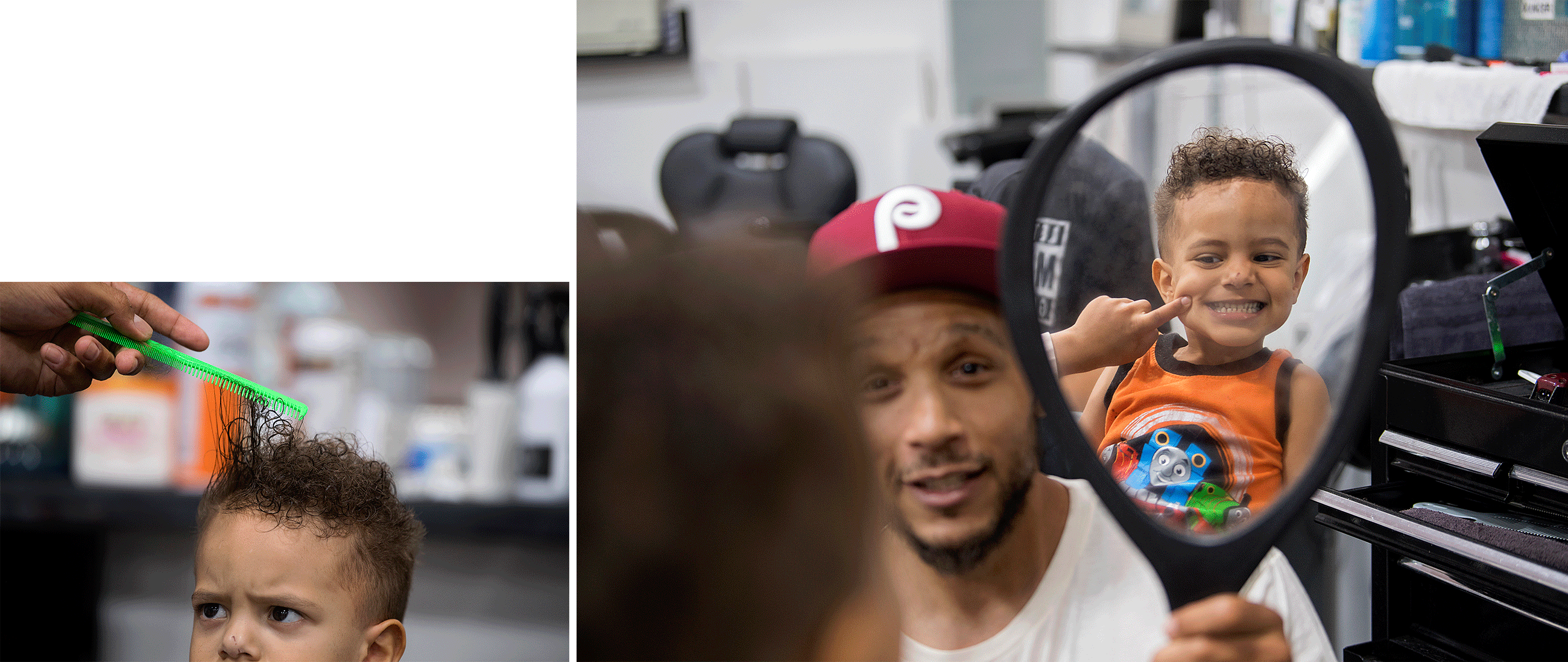

Tobias Adams’ scraggly head looked comically tiny poking out of a barbershop cape made for a full-grown man.

As the 3-year-old perched atop a box on the barber’s chair, he locked eyes with his mom, Jasmine Adams.

“I’m brave,” he said. It was part boast, part self-affirmation.

“Yes, you are, baby,” she responded.

“I’m brave,” he repeated.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Tobias hardly flinched, even as the clippers tickled his ears during his first-ever haircut on June 29. His family — mom Jasmine, dad Matt and 7-year-old sister, Arianna — looked on, occasionally tossing out words of encouragement and, near the end, bribes of a post-haircut toy.

The Columbian observed this milestone, too, as part of a series following Tobias between his third and fourth birthday to provide a window into this crucial stage of childhood development. It is a time when children learn more about their bodies and what they can do.

Up until this point, for the extent of his entire existence on planet Earth, Tobias’ hair had only ever gotten longer. Hair, in Tobias’ 3.26 years’ worth of expertise on the matter, exclusively grows.

During the grand haircut reveal in a handheld mirror, Tobias touched his head. He felt the close-cropped fuzz where a tangle of black curls used to be. He realized something on his body had changed.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Tobias looked “like a little businessman,” cracked the barber and self-proclaimed “kid whisperer,” Chaz Davis at CeeDee’z Cutz in Vancouver.

(Indeed, Tobias drove a hard bargain with Davis on the post-haircut lollipop exchange and negotiated him up from three to five.)

Three-year-olds are just gaining self-awareness of their bodies and how they can change. A banged-up knee hurts, bleeds and then heals. Hair grows long but can be cut without pain. And bodies get bigger, stronger, and better at doing stuff.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Having a ball

On May 18, Tobias gave soccer a try.

He loved kicking a ball around the yard, Jasmine said, and she thought they’d try a more organized version with Lil’ Kickers. Tobias was on the cusp between groups — Thumpers for 2- to 3-year-olds, and Hoppers for 3- to 4-year-olds.

Jasmine and Matt decided to give the Hoppers a try. Which is how, on a Saturday morning, they found themselves at Salmon Creek Indoor Sports Arena watching their youngest scramble around a field with slightly older, slightly more coordinated kids wearing soccer jerseys.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Tobias, if you’ll excuse the pun, had a ball.

He dodged around cones! He hopped over colored dots! He kicked a soccer ball down the turf! He even rolled around in a parachute, surrounded by yet more balls!

Turn-taking, though, proved a challenge. Lining up was a mere suggestion. And why would he run this way, when his family was watching him from over there?

Maybe, Jasmine considered, they should’ve gone with the Thumpers.

But it was no matter to Tobias, who had (quite literally) the time of his life. When the class was over, it was (quite literally) the end of the world.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

The organizational bits may have been tough, but when it came to what’s known as gross motor functions, or whole-body movements, the little guy killed it, running and jumping with the best of those seasoned 4-year-olds.

To help 3-year-olds along in their physical development, the best thing a caretaker can do is encourage opportunities to move, said Sara Waters, an assistant professor of human development at Washington State University Vancouver. Practice — for running, walking, skipping, climbing, balancing, navigating stairs, bike-riding, somersaulting, and just generally bopping around the universe — makes perfect.

“The more exposure you get to something, the more practice you have with something, the better you get at it,” Waters said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists a few physical milestones that a typical kid should reach by 3. By their third birthday, most children should be able to climb, run easily, pedal a tricycle and walk up and down stairs, one foot at a time.

By 4, the CDC’s list expands to include more refined skills like hand-eye coordination. Children at that age should be able to catch a ball bounced in their direction most of the time. They should be able to hop on one foot, and balance on one foot for at least two seconds.

Tobias is well on his way. He can jump off one foot but has to use both feet to land, at least as of mid-July.

“Between 3 and 4, we would expect to be able to see a child stand on one leg,” Waters said. “They might not be able to balance very long at all by 3, but by 4, we’d expect them to be able to balance a little longer.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

“The amount of strength and stamina they show should be increasing,” Waters continued. “They can pick up heavier things, run around for longer periods.”

It’s not a precise formula, and kids advance at different rates, she said. It’s more of a progression. Some kids develop gross motor function faster than fine motor function, and vice versa.

External factors affect physical development, too. Nutrition plays a big role in how a preschool-aged kid grows. Even a brief period of malnourishment can stunt growth for years afterward, research has found. On the other hand, overfeeding children at this point in their lives increases their chance of weight issues and obesity later.

Tobias, for his part, eats a varied diet, but his favorite foods are meat and fruit: think paleo, but with more lollipops.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Drawing a picture

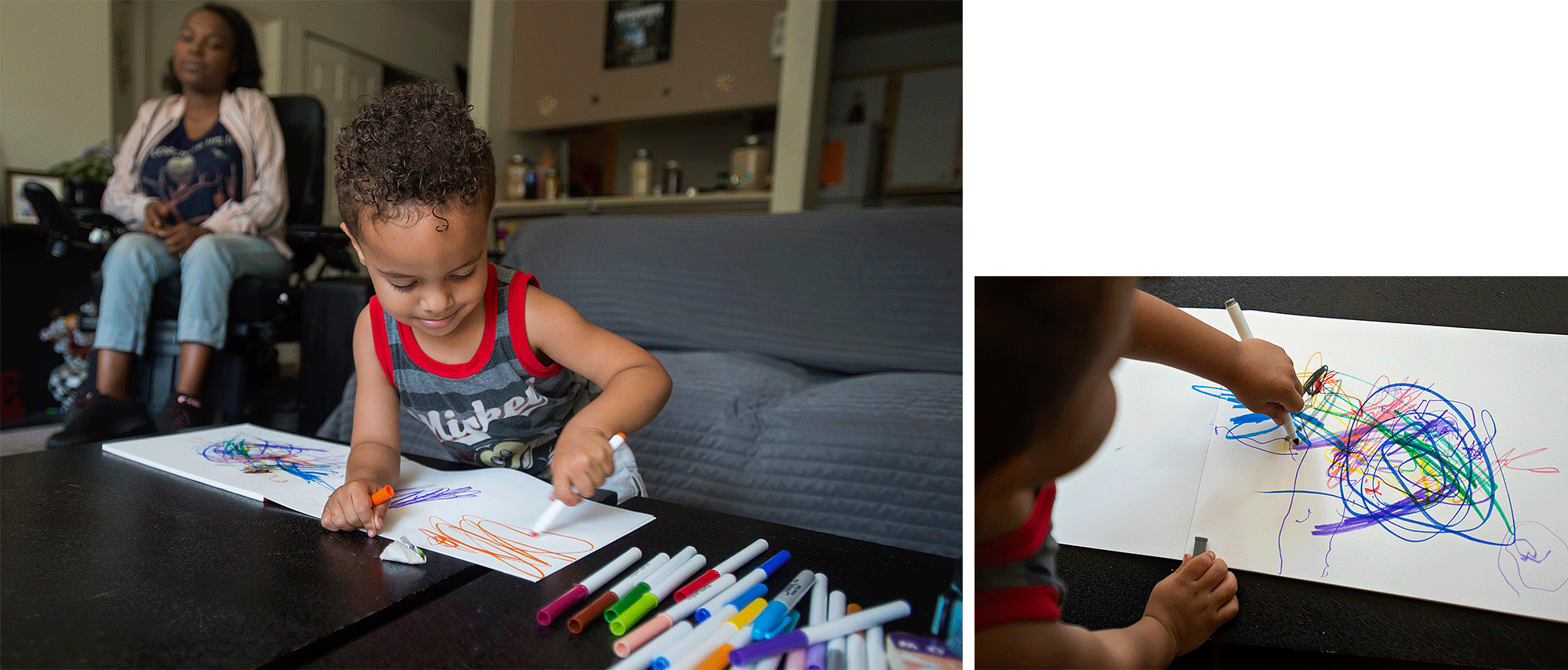

Sitting on his bedroom floor in the Adams’ Minnehaha home on July 16, surrounded by a rainbow of markers, Tobias looked down at a drawing pad. It was open to a blank page.

Then, with tremendous confidence, he drew the following:

• A self-portrait.

• A T. rex.

• A zombie.

• Grapes.

• A flower garden.

• Columbian reporter Calley Hair.

He knew he should draw limbs and features. He’d start with a head, then add eyes, and sometimes arms. Sure, they were unintelligible. By the time he came to the legs, he’d moved onto the next subject, or thrown in a few scribbles for good measure.

But he could usually get the caps on and off the markers by himself. And he had a grand time. His favorite color was green.

Kimbree Brown, the early learning program manager of the Childhood Development Program at WSU Vancouver, said kids Tobias’ age are just starting to develop enough control of the small muscles in their wrists, hands and fingers to draw a recognizable picture. And as fridge-worthy as random color splotches might seem, it’s exciting to watch distinct forms start to take shape, she added.

“They’re moving from just scribbles, to actually being able to hold a pen or pencil to write letters,” Brown said. “You would be able to tell it’s a sun, or a house, or Mom.”

In the year between 3 and 4, fine motor skills are finally starting to come online. At 3, the CDC doesn’t list any milestones that require manipulating fingers or other tiny muscles. By 4, the organization reports, kids should be able to accomplish some of the more finicky tasks, like pouring liquid or mashing their own foods.

Of course, drawing a picture requires a whole other set of mental skills, including attention span. After oohing and ahhing over the Tobias/T. rex/zombie/grapes/garden/reporter scene, Jasmine encouraged Tobias to try something a little more structured.

“Let’s draw something together,” Jasmine said. “Do you want to draw a rainbow? I’ll start.” She drew an arc of blue, then an arc of red, nestled into the same curve.

Tobias gave it a shot, swooping the orange and red markers. For such a finely tuned task, he came pretty close — the end result was, indisputably, a rainbow. The skills were there. He just needed a little nudge.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Self-awareness

At 3, kids are starting to get a sense of themselves and how they work.

In the transitions from babyhood to toddlerhood to childhood, they gain more independence. They start to do more and more with their limbs, strengthening those physical muscles along with the connections between the brain and body.

“A baby can’t do a whole lot,” Waters said. “Mostly what they can do is send a signal out to their person that something is wrong. Then the person needs to come and take care of them.”

Between 1 and 2, children start mimicking the behaviors they observe in their immediate surroundings. But as they get older, those mimicking behaviors start to shape their understanding of how their bodies work.

By 3, a child can use his body to achieve an end — running over to that toy across the yard, or scooping this bite of mac and cheese onto his fork.

“You’ll kind of see them switch back and forth” between mimicking and deliberate action, Brown said, “as they build some of their skills.”

But at this age, there are definitely limitations to how thoroughly we humans understand ourselves.

For example, our grown-up conceit of “mindfulness,” of paying attention to how our bodies feel in any given moment, is out of grasp until around kindergarten, Waters said. That’s when kids start to develop some more advanced self-regulation skills, like taking deep breaths to calm down.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Caretakers can ask basic self-awareness questions of their 3-year-old: How do you feel? Are you angry? Happy? Tired?

“We can start laying the foundation for that by using a lot of internal or ‘mental state’ language. They may not understand it yet, but we’re laying that foundation,” Waters said.

For Tobias, the primary influences in his life are his immediate family: His dad, his big sister and his mom. Grinning up at Matt at the bathroom sink, Tobias learns by example how to brush his teeth. He flips around the living room with Arianna, who’s taken gymnastic classes.

Jasmine uses a wheelchair because she has spinal muscular atrophy, a genetic disease that affects the nervous system’s ability to control voluntary muscle movement. In that way, Tobias’ experience lies outside the norm. He hangs off her chair as comfortably as any kid hangs off their mom’s hip.

Exposure to a lot of different types of bodies early on can deepen a young child’s understanding of how they function, Waters said.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

“You might see a different level of awareness of the range of bodies, and how bodies work, because a lot of kids don’t have those experiences,” Waters said. “If you have a lot of exposure to somebody who has a disability, you’re aware of that.”

Brown said that having a family member with special needs is unlikely to affect a child’s physical development as long as he has opportunities to run and play.

Having a family unit outside the cookie-cutter norm, however, may affect his life socially.

“Families can look so many different ways and still be healthy, functioning families. And often they can give kids a set of skills and an understanding of the world that other families might not be able to give,” Brown said. “Then, that child can offer that to his peers.”

Right now, Tobias’ circle of “peers” is limited. But rumor has it he starts preschool in the fall.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

About this project

Back in January, we sent out a call for a child to follow as part of a series examining what it’s like to be a 3-year-old in Clark County.

We received an outpouring of responses from parents, and we sat down with a few families from around the region before selecting Tobias and the rest of the Adams clan.

We chose to spotlight a 3-year-old because kids undergo tremendous changes in their emotional, social, mental and physical development as they transition from toddlerhood to childhood.

We picked up with Tobias on his third birthday, on March 28, and the first installment of this series published on May 12. We’ll follow Tobias through his fourth birthday. Of course, every child is different, but we hope that family, caregivers, friends and loved ones of little ones around Clark County find moments along this journey that they can relate to.