Dream of becoming a professional wrestling star packed with passion, pain

Kylan Rowland woke up feeling the pounding he took the night before.

The soreness in his back was familiar, something he has endured for nearly a year.

The neck pain whenever he turned his head was new.

“The day after is always the worst,” Rowland said. “Icy Hot is king. I lather myself up in that.”

The Vancouver resident dreams of making it to the top in professional wrestling, to the WWE’s flashing lights, blaring music, sold-out arenas and monster paydays.

He is starting near the bottom, in a small, dingy gym at a charter school in Gresham, Ore., where the crowds may number slightly more than 100. The wrestlers all have day jobs and set up and break down their hexagonally-shaped ring themselves for every Saturday training session and monthly card of matches.

During his May 28 unsuccessful challenge of Teck Tonik, the Oregon Wrestling Club’s champion, Rowland was repeatedly slammed onto the canvass, with the full weight of his 270-pound opponent landing squarely on him.

“From the top rope — ouch,” he said. “He’s a big boy.”

Enlarge

Nathan Howard/The Columbian

Rowland occasionally wonders what he is doing in times like these, when his 25-year-old body aches like its 40 years older.

“Being sore isn’t ideal, but I just think back to how freaking awesome it was being in the ring,” he said. “I just try to remember the good stuff when the bad stuff happens.”

Enlarge

Nathan Howard/The Columbian

Rowland has experienced both. He was born in Vancouver but bounced back and forth to the Auburn area outside of Tacoma. His family upbringing was rough. His father wasn’t around much. His mother worked whatever jobs she could so he and his sisters always had dinner.

“She was the hardest worker I’ve ever seen,” he said. “I saw her sell T-shirts to put food on the table.”

In middle school, Rowland fell in with the wrong crowd. He started drinking, got into three fights and flirted with expulsion.

In October 2009, a couple of months before his 16th birthday, he was abruptly pulled out of third period at Jefferson High School in Federal Way and told his mother — the woman he considered his “absolute hero” — was dead.

His mother, who had just turned 42, died in a freak accident — electrocuted in an improperly wired hot tub. Rowland and his younger sister went to live with their aunt in Vancouver, and Rowland graduated from Heritage High School.

As devastating as his mother’s death was, it would be a turning point.

“It was a huge wake-up call,” he said. “What am I doing with my life? Where am I going?”

Living with his aunt also got him interested in Christianity. When she finally convinced him to attend church and related activities, he was astonished by how receptive other teenagers were when he opened up about his past.

“I remember three of the kids stepped up with a piece of paper and gave me their numbers,” he said.

Enlarge

Nathan Howard/The Columbian

National Guard

Rowland said he remained “something of a loose cannon” before joining the Washington National Guard in late 2013, shortly before he turned 20. His youth pastor had stepped down to enter the guard, and Rowland followed his lead. Rowland suspects he would have never gone into the guard if his mother hadn’t died.

“I might be in jail,” he said.

Rowland’s lack of discipline changed in basic training when his head was shaved and drill instructors immediately called out any misstep.

“They taught me individual responsibility, all the way to making your bed in the morning,” he said. “And if it wasn’t done right, they just threw it all on the floor.”

Rowland credits the guard with providing structure and fostering strength, which he said allowed him “to carry myself a little higher.”

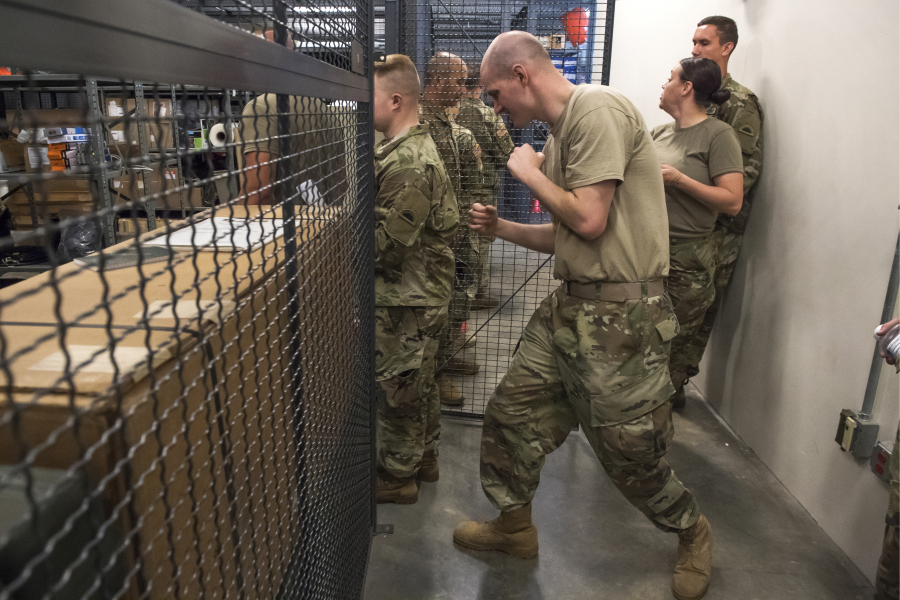

- Kylan Rowland shadowboxes while waiting in line to move equipment during National Guard duty at the Vancouver Armed Forces Readiness Center. Nathan Howard/The Columbian

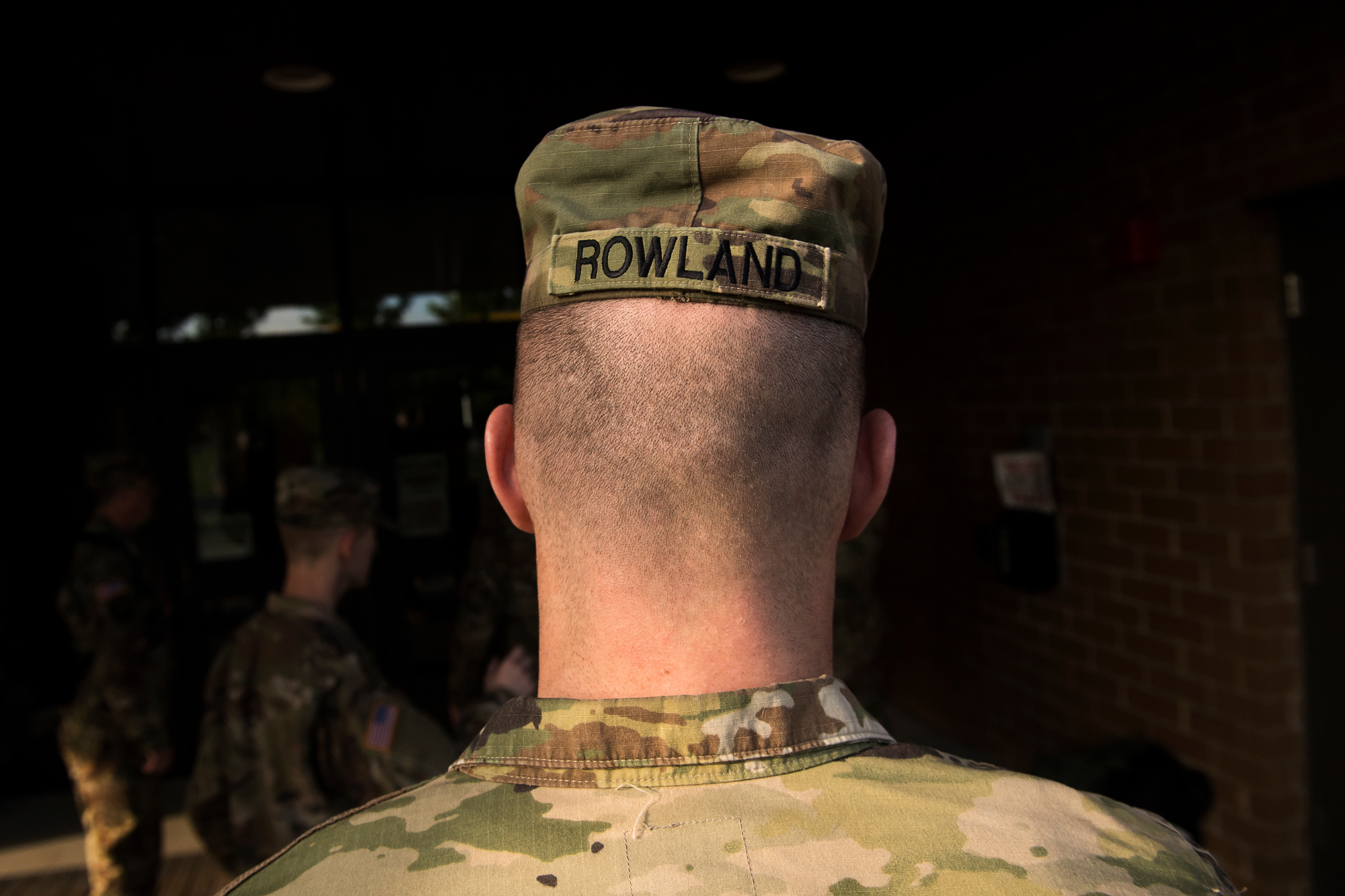

- Specialist Kylan Rowland stands in formation during a weekend drill at the Vancouver Armed Forces Readiness Center at sunrise on June 1. Nathan Howard/The Columbian

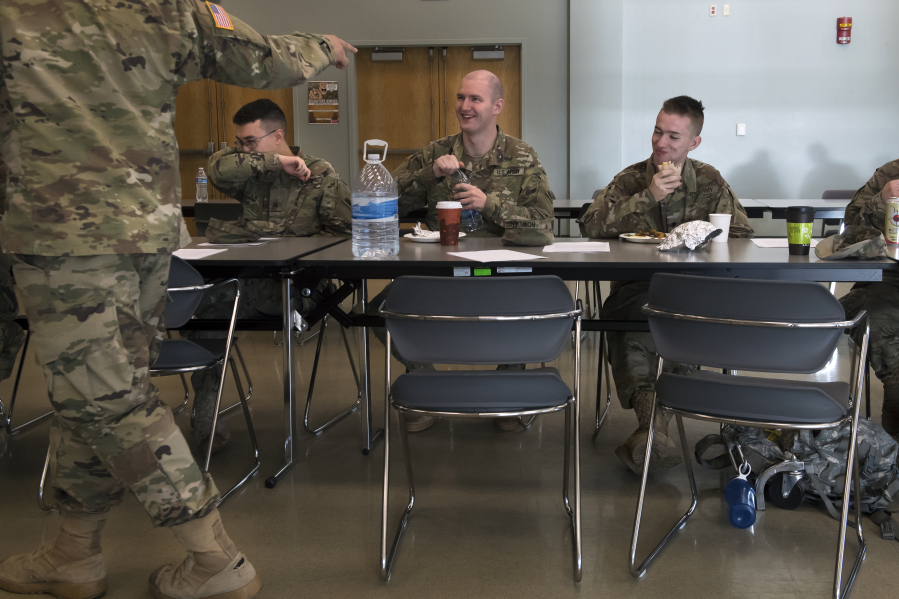

- “You were robbed,” a fellow guardsmen says to Kylan Rowland about his recent wrestling loss to Teck Tonik while walking past him during breakfast. Nathan Howard/The Columbian

In September, Rowland’s unit, I-303 Cavalry, will be deployed to Jordan to support Operation Spartan Shield, which provides both a presence and deterrent in one of the world’s most volatile regions.

Rowland will stay behind in Vancouver to focus on professional wrestling.

“I will admit that it’s bad timing,” he said. “It’s just the simple fact of my contract’s coming to an end. … Deploying would be really cool. It would be an honor because so far, I haven’t deployed.”

“The guard has been good to me,” he added. “Leaving, it’s not like an easy decision. It’s been a dominant factor in my life. If I didn’t have this dream of being a wrestler, I probably would have (stayed in the guard).”

‘Larger than life’

Professional wrestling “always has been larger than life,” he said, since he first saw it on television when he was 4. Rowland said he long dreamed of becoming a professional wrestler, but it was always “maybe next year, maybe next month.”

The wait ended last July when Rowland Googled professional wrestling, discovered the Oregon Wrestling Club’s Facebook page and contacted the group. He attended the club’s Independence Day card in Corbett, Ore., where he helped set up for the show and worked security during the matches, making sure no overly enthused spectator interfered with the wrestlers.

Enlarge

Nathan Howard/The Columbian

“I was grinning cheek to cheek the whole time,” he said. “I thought this was it. This is the first step of getting where I want to be.”

Three days later, he started working out with the club’s wrestlers at Rockwood Preparatory Academy in Gresham.

Weekly training

On a Saturday morning in April, a small group of wrestlers started their weekly training session by stretching individually or in small groups.

Meanwhile, Cameron Star and other wrestlers arrived in the gym. Star is the Oregon Wrestling Club’s leader. Rowland considers him a mentor, someone who is smart, dedicated and a source of valuable coaching on footwork and other fundamentals.

Enlarge

Nathan Howard/The Columbian

Once warm-ups were over, the group moved into the six-sided ring. Under Star’s tutelage, they started with simple back bumps, where each wrestler throws himself backward on the mat, tucking his chin to avoid cracking the back of his head and trying to disperse the impact across as large of an area as possible.

Next came hip tosses, where one wrestler hooks the arm of the other, using momentum to flip him over onto his back. They took turns hurling each other into the ring’s ropes and turnbuckles, which connect the ropes to the ring’s steel post, then paired that maneuver with a drop kick.

When Rowland hit the canvas, he made a point of reaching around to his lower back, partly to practice selling the move — but also because it hurt.

Sounds from the ring echo through the otherwise deserted gym. The ring makes so much noise that Star’s quiet voice is only faintly audible.

“That’s a little patty cake,” Star said to one wrestler. “If you’re going to do it, make it look good.”

“He’s a little soft spoken,” Rowland said about his mentor. “He’s subtle, but he’s also a stickler.”

Military persona

Rowland has incorporated his military service into his character. For his May 28 match, he wore a camouflage singlet and tactical vest into the ring. The previous month, he saluted a young boy at ringside.

Enlarge

Nathan Howard/The Columbian

Performing in such a small venue means interaction with the audience is nearly one-on-one, with a wrestler occasionally answering a spectator. During his May 28 bout, Rowland could hear a few fans chanting, “Teck is going to kill you.”

Teck Tonik is a crowd favorite, a “face,” short for baby face in wrestling vernacular. Every face needs a villain or “heel” to battle. Rowland also is a face, playing up his military background and coupling it with raging intensity.

“In the ring, I am a big ball of energy,” he said. “My natural strength is ‘happy-go-lucky guy, everybody loves me.’ I think it would be fun to go in the other direction someday.”

For his debut match on Feb. 23, Rowland said he sold about 60 seats to friends and could hear people chanting his name as he came out from the locker room.

“I will never forget the full adrenaline rush that went through me,” he said. “They fuel me, they absolutely fuel me.”

Acting as an over-the-top maniac, ready to go berserk at the sound of the bell, is a little more difficult for him than firing up the crowd before the match starts.

“I was raised by all women, so naturally I am on the softer side,” he said.

‘I have no shame’

He is blessed with a showman’s streak, which also can be seen as he trains to be a karaoke DJ. Rowland has performed as assortment of songs, from Johnny Cash to the Beastie Boys.

“I have no shame,” he said. “When I started, I had a reputation for doing girly songs.”

Enlarge

Nathan Howard/The Columbian

As for wrestling, Rowland said there are “10 million things” he could work on to improve his overall performance. Unlike some of the club’s other wrestlers, he is tall and lean, 6 foot 2 inches and a trim 215 pounds, more lanky than gargantuan. He works out at Planet Fitness because it’s cheap and open 24 hours, a necessity for someone who works swing shift at Reddaway Trucking in Portland. He tries to hit the gym at least three times a week. “More is great, less is tough,” he said.

He understands he needs to bulk up to make it big in professional wrestling but wants to do it the right way, combining workouts and diet changes — without resorting to steroids.

“I have no intention of messing with that. Zero,” he said.

‘Bigger than myself’

There is a common thread between Rowland’s National Guard service and his fledgling wrestling career.

“It was part of the same mentality, about being bigger than myself,” he said. “It’s taking ordinary people and making them larger than life, making them icons, villains.”

He pauses for a second and mentions how one of his sisters attended beauty college and has a passion for cosmetology and hair dressing.

“I never had my thing — until this,” he said.

Rowland considers wrestling more sport than performance. “In theory, you compete for championships and prizes,” he said.

For now, those prizes are paltry.

Brock Lesner, one of the WWE’s superstars, reportedly earns $12 million a year and up to $500,000 for big matches.

For his May 28 championship match, Rowland pocketed $50.

He pays the Oregon Wrestling Club $25 every Saturday he trains with the group.

Rowland understands he’s starting near the bottom, but his eyes are set on the top.

“I am going to work my butt off to get as far as can,” he said. “I’m shooting for the stars on this one.”

His next star: A wrestling card on June 29.

He’s already stocked up on Icy Hot.