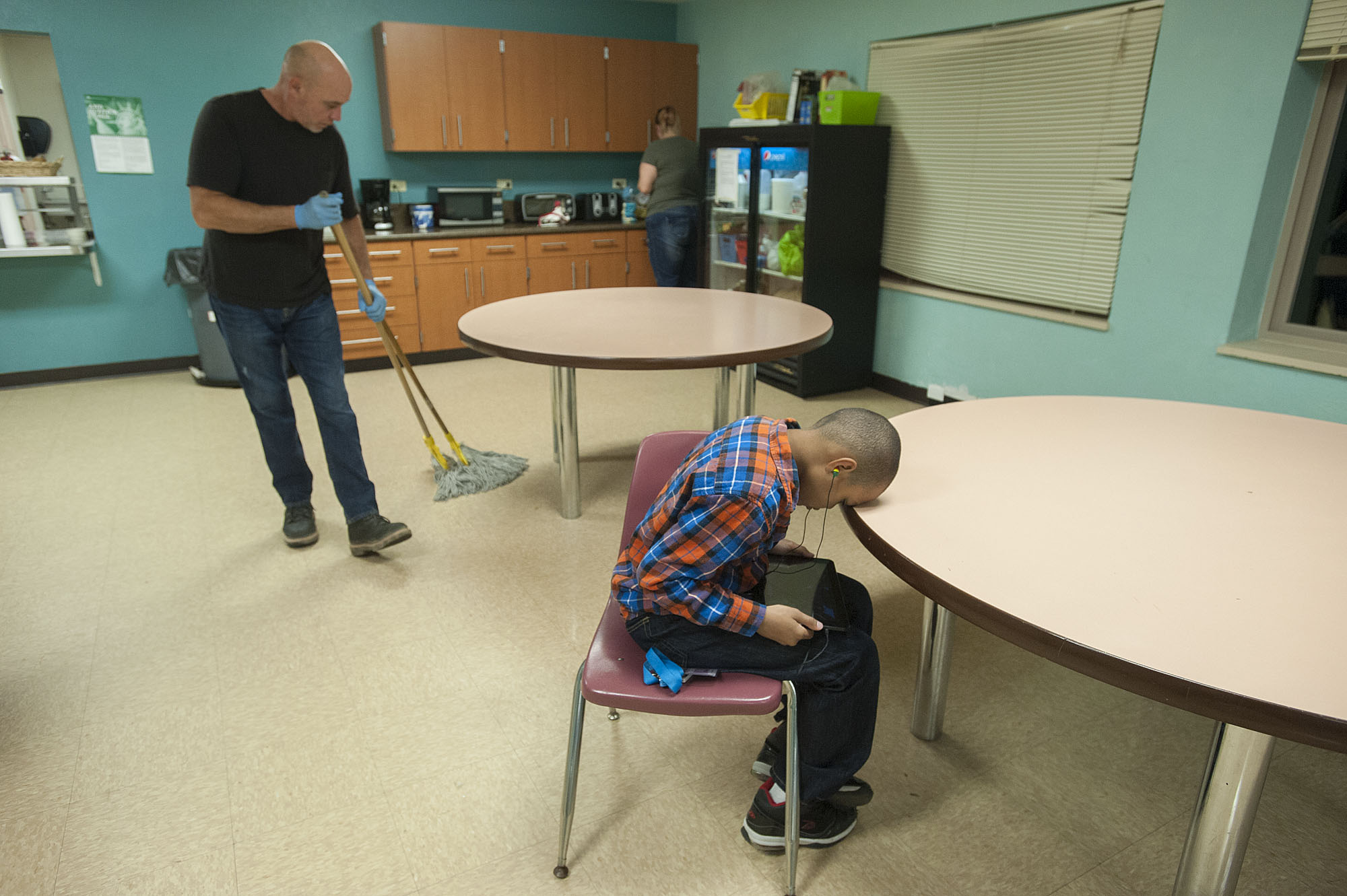

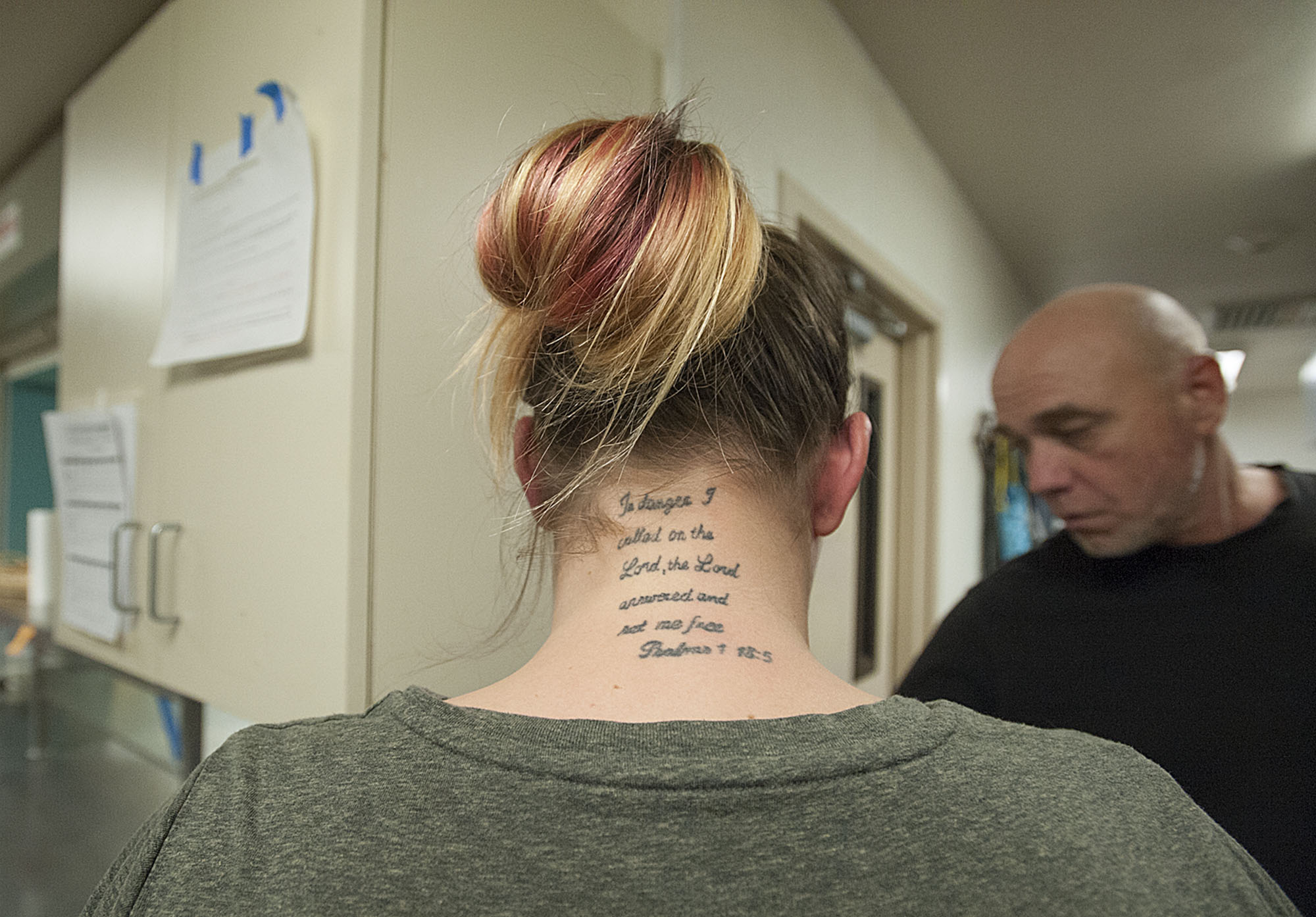

Candi and John Stocks and their son have lived in a lot of places. They’ve stayed in a church and in homeless shelters on different sides of town. They’ve doubled up with Candi’s parents and recently they slept in a Honda Odyssey minivan.

Currently, they live at Share Orchards Inn, a 12-room shelter for families and women across the street from Orchards Park.

“We’re trying to make good choices and dig out of this hole,” John, 53, said. “For us, we want it to be a stepping stone and help us to get out of here.”

When their van was on the fritz, they decided to call the Council for the Homeless and try to get inside. A few weeks later, they got a room at the Share Orchards Inn.

“Just the best thing for us is having some place to call home temporarily,” Candi, 31, said.

'We’re trying to make good choices and dig out of this hole. For us, we want it to be a stepping stone and help us to get out of here.' John Stocks

The Stockses and their 9-year-old son Isaiah Pippin are among 1,206 people, including 405 children, who have used the local shelter system so far this year, according to data from the Council for the Homeless that goes through the end of October. For all of those people who got shelter space, 2,550 people were turned away — 166 more than in the same time period last year.

Orchards Inn has 11 family rooms as well as one room for four single women. Share’s sister shelter, Share Homestead in Hazel Dell, has the same setup. Share took over operating the shelters, which can each accommodate up to 50 people, in 1996. Share House in downtown Vancouver has 30 beds for single men. The shelter was rebuilt in 1999 after a fire destroyed it in 1996.

In addition to managing all three shelters, Share provides other services for homeless people.

There are currently 99 additional shelter beds because the temporary Winter Hospitality Overflow shelters opened this month at two churches in Vancouver.

“We certainly have a growing issue that needs to be addressed,” said Amy Reynolds, the deputy director of Share. “People who live in the shelter have no other options. If you could stay with your friends or family, you would.”

Share had hoped to address homelessness from a housing perspective so there wouldn’t be a need for more shelter. The plan was derailed by the Great Recession and the tumultuous years that followed.

Shelters are one of the costlier interventions and only temporarily alleviate homelessness. Share spent $900,000 last year to run its three permanent shelters. It’s also difficult to find funding for new shelters. Nationally, the trend has been to move away from shelters and focus more on programs such as rapid rehousing and permanent supportive housing.

“That doesn’t seem to be what our community wants or what our community needs,” Reynolds said. In Clark County, there’s a push for more shelters.

When Reynolds started working at Share 15 years ago, she said there would occasionally be vacant rooms at the shelters in the summertime.

“We never see that anymore,” she said.

As rents have gone up — pricing out families that used to be able to afford the rent — demand for emergency shelter has gone up, too.

“We know it from our direct experience, we know it from the people we work with, but we also know it from studies that homelessness in a community correlates most strongly with housing prices,” said Andy Silver, executive director of the Council for the Homeless. “What we’re seeing in our community is a result of just extreme rent growth.”

Elusive housing

These days, people need more time to transition out of shelters. In the last year, Share increased the amount of time families can stay at the Share family shelters from 60 days to 90 days. Share found that families were struggling to find housing in two months and needed more time. Families can also get a 30-day extension if housing options fall through, or if they’re working and need to save more money before they can move.

There’s resistance to making shelter stays longer and longer; after all, a shelter is supposed to be an intervention for homelessness, not a solution.

The Stockses have experienced firsthand that struggle to secure housing and get out of the shelter as quickly as possible.

When Isaiah started school, the family learned about housing assistance programs that prioritize families in the district. It felt like everything that needed to happen had happened. They got into shelter quickly, John got a job, they replaced the van and they were selected for a federal Section 8 housing subsidy voucher.

“We were feeling lucky,” John said.

Then Vancouver Housing Authority told the Stockses that they didn’t qualify for assistance because John made too much money for their family of three. He works in construction pouring concrete and his wages can vary from paycheck to paycheck. The Stockses believed his wages were calculated improperly and appealed the decision. Also, Candi had sent her two daughters to live with family in Georgia so they didn’t have to contend with living in a van or a shelter.

The girls have since been added to the family’s application, qualifying them for assistance. The Stockses received a 30-day extension at the shelter. If everything works out, they won’t be homeless much longer.

Tight budgets

At Share’s family shelters, there is one staff member on hand during any one shift.

“We run a pretty slim staff,” Reynolds said.

Labor is the biggest chunk of the $900,000 cost of operating the shelters. More money could go toward more beds or more staff to work with clients, who would then have greater success getting and keeping housing. As a nonprofit entity, Share’s money comes from government grants, donations and fundraising.

Still, larger staff-to-clients ratios can work. One part-time staff member worked with the 12 women staying at Women’s Housing and Transition, or WHAT, a low-barrier shelter that Share opened in April. The overnight shelter for single women — aimed at those who don’t typically access emergency shelter — was at St. Paul Lutheran Church and ran through the end of October. Unlike Share’s other shelters, clients could have pets with them and they could show up intoxicated.

Are you homeless? Here’s where you should start:

Step 1: Call the housing hotline at 360-695-9677 to get evaluated and on the list to receive emergency housing. Call 211 to get directed to other resources you may need.

Step 2: If you’re hungry, there are many places you can get a free meal:

- Share House at 1115 W. 13th St. serves hot meals three times a day on weekdays: 6:30 to 7 a.m., 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m., and 5 to 5:30 p.m. On Saturday and Sunday, meals are served 9 to 9:30 a.m. and 3:30 to 4 p.m.

- The Proto-Cathedral of St. James the Greater hosts a free dinner every Thursday from 5 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. The church is at 218 W. 12th St. in downtown Vancouver.

- Refuel Washougal offers a free meal every Friday from 4 to 6 p.m. at the Washougal Community Center, 1681 C St.

- Lost and Found Café offers meals from 6 to 7 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays at Zion Lutheran Church, located at 824 N.E. Fourth Ave. in Camas.

- Live Love Center at Living Hope Church serves meals from 11:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Wednesdays, and 2 to 4:30 p.m. Saturdays at 2711 N.E. Andresen Road.

- Angels of God serves lunch 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Monday through Friday, at Memorial Lutheran Church, 2700 E. 28th St.

Step 3: Find a safe place to stay during the day. Share’s day shelter at Friends of the Carpenter is open 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily at 1600 W. 20th St. Libraries are places where all are welcome, so long as patrons abide by the rules. The Vancouver Community Library is open 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Thursday, and 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Friday through Sunday.

— Patty Hastings

During the seven-month period it was at St. Paul, 46 women used the shelter and 13 of them moved into permanent housing.

“We had a bigger success rate than we had anticipated,” Reynolds said.

The shelter couldn’t remain all year at St. Paul, which also hosts the Winter Hospitality Overflow shelter for single men that opened earlier this month. After Shared searched for, vetted and worked with different churches that could take over the WHAT, St. Luke’s Episcopal Church recently signed on to become the new location. They aim to open the shelter Dec. 5 but have to make some changes to the facility first and rehire staff, Reynolds said. The women’s shelter will run through March.

Setting up a shelter at a church was cheaper and faster than building a new permanent shelter, allowing Share to more immediately address the needs of a vulnerable population.

Building a permanent shelter from scratch is a different proposition.

Prop. 1’s benefits

Reynolds said that now the successful campaign is over for Proposition 1, the affordable housing levy, a task force focused on creating more permanent shelter space will start meeting again. It will look at who needs to be served, how many people a new shelter would house, and where it to put it.

“Should it be a specialized population? Or, how can we be more nimble to be able to match the needs of the community if we create a family shelter and then five years from now our biggest need is couples without kids?” Reynolds said. “How do we adapt to that?”

One idea was to convert Fire Station 1 at 900 W. Evergreen Blvd. into a homeless shelter; it already has kitchen facilities and bedrooms. It won’t be available until at least late 2017, after a new station opens.

Besides money, location and community buy-in are huge hurdles. Not everyone wants a homeless shelter in their neighborhood.

Part of that, Silver said, is that people may not be willing to face the solutions needed to address the community’s homelessness. Rather, because homelessness is horrible and difficult to mentally deal with, the human reaction may to be to dehumanize homelessness: “People are choosing to be homeless. They’re not really from this community. They’ve done something to deserve being homeless.”

This mindset, this “othering” of homeless people, he said, “prevents the community from stepping up and responding because it’s not really our problem. It’s somebody else’s problem that’s just come into our community.”

Other people believe that homeless people move into their community because they have excellent services, and by building a new shelter Clark County will attract more people who are homeless.

“It just completely is not true,” Silver said. “We have terrible access right now to emergency shelter and other services in our community and we still have people who are homeless.”

'Hopefully we can get to that level of action here without getting to that level of crisis.' Andy Silver, Council for the Homeless

Maybe the homeless crisis just hasn’t reached a boiling point. Neighboring Portland has a much bigger problem but has also “been able to come together as a community and quickly find a location and a fund and open up new emergency shelter,” Silver said. “We have really failed at that here.”

That means Portland got past those myths surrounding homelessness with enough people, Silver said.

“Hopefully we can get to that level of action here without getting to that level of crisis,” he said.

Both Vancouver and Portland, however, recently received community buy-in. In Vancouver, voters approved Proposition 1 earlier this month to bring in $6 million in taxes annually for seven years. Portland voters said ‘yes’ to a $258 million bond measure to fund more affordable housing.

Thirty percent of the money Vancouver collects through the levy can be used to prevent homelessness by providing rent vouchers, self-sufficiency services and building shelters.

People frequently forward Reynolds ideas for addressing homelessness that they see being used around the country. While she likes looking at the ideas, when it’s all said and done, Reynolds said she thinks that Clark County won’t be an exact replica of some other place. It won’t look just like Portland nor does it require the same scale of response.

Rather, she envisions a puzzle made up of different ideas and models that pieces together a solution that’s just fit for us.

Patty Hastings: 360-735-4513; twitter.com/pattyhastings; patty.hastings@columbian.com