Most people spent Fourth of July celebrating America in all its star-spangled red, white and blue glory.

That afternoon, Steven Crews was smoking in his tent on the Vancouver waterfront. He’d been there about a week and planned to meet family for the holiday. When police approached, he threw something into the bushes; they thought it was a drug pipe, though nothing was located. The 47-year-old was arrested and later pleaded guilty to unlawful camping and tampering with physical evidence. As Fort Vancouver’s annual fireworks display dazzled thousands of onlookers, Crews was in jail, unable to make bail.

“It’s not fair. I’m not camping, I’m homeless,” said Crews, who had been living out of his Ford Focus for eight months. He said he lost his apartment after rent went up. “All we want is a little bit more leniency, a little bit more change. We’re all trying to get off the streets.”

Crews has not paid the $100 fine for unlawful camping.

He’s one of 96 people who were cited during the first year of the revised unlawful camping ordinance; the law makes it illegal to camp in a public place between 6:30 a.m. and 9:30 p.m. It used to be that camping was illegal in Vancouver at all times.

Last year, the Department of Justice ruled it unconstitutional to ban people from sleeping outside when adequate shelter space does not exist.

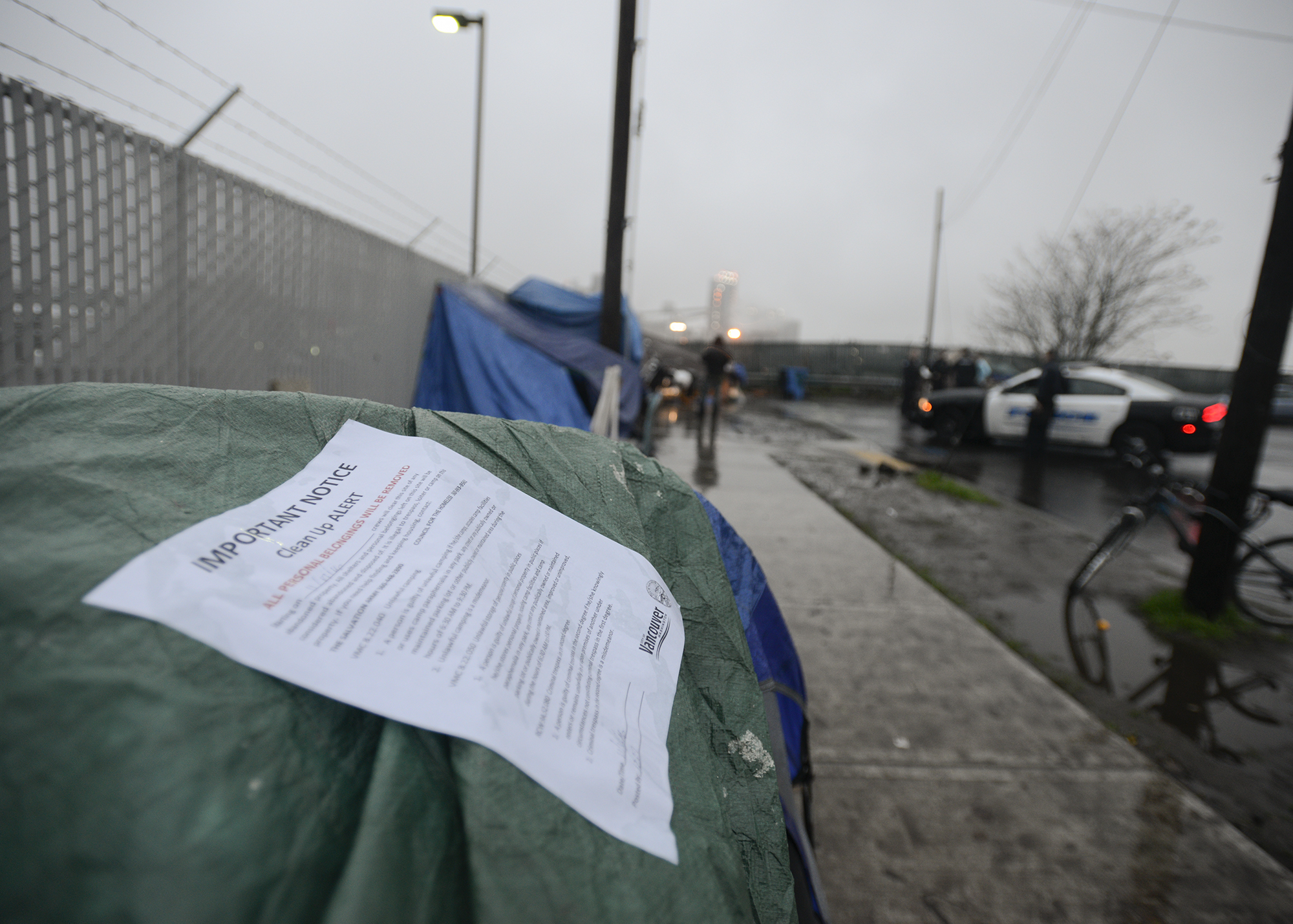

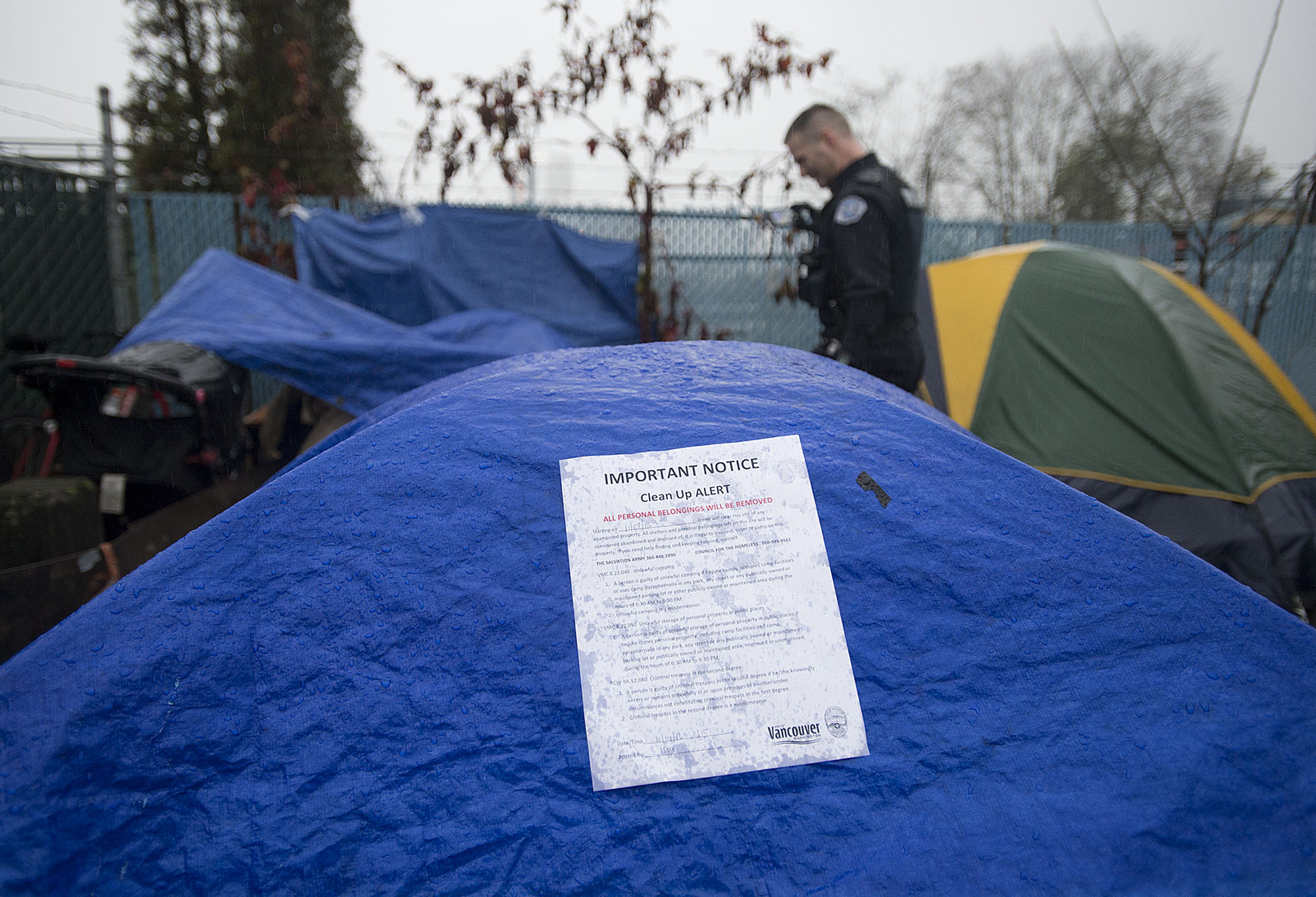

The ordinance was suspended for a short time and the number of tents multiplied around Share House, the men’s homeless shelter in downtown Vancouver. The revised ordinance was made into law and enforcement began Nov. 3, 2015 — one year ago this month.

Camps still pop up around Share House. When Crews talked one recent Friday afternoon, there were people, cars, shopping carts full of stuff and about 15 tents around West 12th Street and Lincoln Avenue. A police officer drove through, along with people giving out snacks, bottled water and clean towels.

Hundreds of people in Clark County still spend their days and nights outside. And that’s no surprise to advocates who say the homeless are just spread out. They’re hiding or roving around the community, unable to access the overwhelmed homeless service system.

“When the current camping ordinance was passed, there was discussion about how this was a temporary measure to have something on the books that complied with the law, the Constitution, but there would be ongoing conversations about how to make this work,” said Andy Silver, executive director of the Council for the Homeless. “And I think those haven’t really occurred in any real way. What we’ve been left with is a system where there’s not nearly enough emergency shelter.”

Silver’s agency in Vancouver fields calls from people seeking emergency housing — those who are homeless or on the brink of it. This year, requests for help went up 40 percent from last year. Without enough available accommodations, people are turned away or shifted to waiting lists. The situation hasn’t really improved for unsheltered people.

“This country is supposed to be the great America — you know, land of the free, home of the brave. We help Americans. We’re supposed to take care of our own and we’re not,” Joey Gagnier said. “These people are living in horrible conditions.”

This country is supposed to be the great America — you know, land of the free, home of the brave. We help Americans. We’re supposed to take care of our own and we’re not. Joey Gagnier

The 30-year-old was cited in September while sleeping in a sleeping bag next to his belongings. Gagnier has a warrant out for his arrest but doesn’t want to turn himself in and risk losing his stuff or leaving his girlfriend alone. He said he doesn’t have enough money to pay for the citation anyway.

Only two people have paid their fines in full, according to data from Clark County District Court.

Gagnier said he’s waiting to get subsidized housing. Although he wants to get clean and sober with his girlfriend, he said it’s tough to do that while living outside. Besides struggling with heroin addiction for the last couple of years, he’s also used methamphetamine.

“I don’t want my legacy to be a junkie who overdosed,” Gagnier said. “I’m ashamed. I’m embarrassed about where I’m at.”

How police respond

Vancouver police Lt. Greg Raquer realizes that people living on the streets need social services rather than police intervention. He covers the west side of the city where much of the area’s homelessness is concentrated and people most often get unlawful camping citations.

During a cleanup of camps near Share House last month, police didn’t cite anyone. They worked with people to determine what could be thrown away and what arrangements could be made to store belongings. When encampments get large they become a nuisance and health hazard, Raquer said.

He said his officers give people warnings and plenty of opportunities to cooperate. What often happens is the officer won’t cite somebody, but will tell the campers that they’ll return the next day. If the camp is still set up, they get cited. This arrangement is talked about in many of the court documents associated with camping citations.

“Our first response is not to hand out a ticket, but to educate,” Raquer said. The Vancouver Police Department spent time prior to Nov. 3, 2015, handing out pamphlets and telling people about the change in the law.

Still, Raquer’s agency has to respond to complaints and enforce the ordinance. While the homeless may say they think they’re given too many tickets, businesses and residents say enough isn’t being done to address the problem.

“We’ve got to balance what’s beneficial for everybody,” Raquer said.

In total, Vancouver police have given out 150 tickets to 96 people. Often, people get cited for camping and for storing personal property in public. Or, they may get a criminal trespass charge, too, depending on where they were camping.

Nearly half of the people getting citations are millennials like Gagnier — those born in 1980 or later. Gagnier said he grew up in a middle-class family in Gladstone, Ore., and became homeless five years ago after losing his job cooking at a restaurant. He’s burned bridges with his parents and said he can’t live with them.

“What am I supposed to say to them? I mean, really,” Gagnier quipped. “Oh, things are going great, you know. Over at the Share House I saw a couple tweakers fighting today and somebody ripped me off again.”

Unlawful camping and unlawful storage of personal property are lower level crimes, said Grant Cole, an associate attorney with Vancouver Defenders.

The criminal defense attorneys, based out of an office in Uptown Village, have a contract with the city to represent people who qualify for court-appointed attorneys.

“I’m personally not a fan of the unlawful camping ordinance,” Cole said. While the revised ordinance is more accommodating than the old one, he said it still criminalizes homelessness. Like any other conviction, it shows up in a person’s record during a background check, Cole said. Having that blemish could impact a person’s chances of securing housing or a job.

Amy Reynolds, deputy director of Share, said she sees the bitter irony in someone being denied housing because they got a citation for living outside.

“Does it change the situation? Not really sure,” she said. “In the end, tickets, no tickets… it doesn’t change the concern around there’s no place to go.”

Longtime Vancouver resident Ceci Smith is not surprised that downtown, particularly the blocks surrounding Share House, are a hot spot for camping citations. She lives in Hough, blocks from Share House.

In the end, tickets, no tickets… it doesn’t change the concern around there’s no place to go. Amy Reynolds, deputy director of Share

“The concentration of services is creating this problem,” she said. “I don’t see much improvement going on down there.”

Services for homeless should be more spread out throughout the city and county, not just in downtown Vancouver, she said. This isn’t not-in-my-backyard culture, it’s about serving more people wherever they become homeless and not just downtown, she said.

Smith is a former Vancouver Housing Authority board member and is co-chair of the Vancouver Women’s Foundation, a giving circle that provides financial assistance to struggling women.

Neighborhood cleanup groups have gotten tired and frustrated by the ongoing mess created by the lack of places for homeless people to go, she said. And, residents, she said, feel their input has been left out of recent conversations on how to address homelessness.

No place to go

Last month was the wettest October on record, measuring more than 8 inches of rain in Vancouver. The weather is getting colder and the days shorter. Though it is legal to sleep outside in public places between 9:30 p.m. and 6:30 a.m., the prime spots for getting out of the elements — shelters at parks and underneath overpasses — are off-limits during the times it’s legal to camp.

While people aren’t supposed to have their tents pitched outside of legal hours, Raquer said people can still be in public places with their belongings. A problem arises if somebody stores their stuff on public property.

“If you can’t be in one spot with your things, then what the hell are you supposed to do? There’s no other choice,” Gagnier said. “You can’t just pick them up and hold them when you have a whole cart full of things. There’s just got to be a better way.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

During those evening hours after the west Vancouver day shelter closes, the homeless can’t legally set up a shelter. There are few options for places to go. Do you go to the library and risk getting kicked out? Do you stash your belongings somewhere, risking that they might get taken, or bring them with you? Each decision has real repercussions.

“To put it another way, there is no camping ordinance that is going to be workable for everyone because the problem is not whether people should be allowed to camp or not. The problem is that we don’t have places for people to go to get them out of the elements,” Silver said. “As long as we have large numbers of people who are forced to sleep outside and be outside during the day with their belongings, those three groups — people who are homeless, other community members and law enforcement — are going to have a tough relationship with each other.”

When the day center opened in a warehouse space at Friends of the Carpenter in west Vancouver in mid-December, it was envisioned as the start of something grander. People had a safe, dry place to be during the day, access lockers and collect mail. The plan was that months later showers would be built, along with restrooms and laundry facilities.

But, those accommodations can’t be constructed because the city wasn’t able to get an easement from neighboring property owners. There’s increased truck traffic and the bus stop that used to be just outside the warehouse was recently removed, said Peggy Sheehan, Vancouver’s community and economic development program manager. Sheehan is in the process of trying to make another space a viable option to build a day center.

This last year, nonprofit leaders and community members have tried — with mixed success — to get new services off the ground to help the homeless.

The Clark County Safe Car Camping Program was established. Days before Christmas, St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Washougal began hosting people living out of their vehicles. It’s almost Christmas again and no other churches have joined the program. Some churches informally host car-camping families, often those who already belong to the congregation.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Faiths groups also tried to get a tiny house village off the ground, but the plans fizzled because a prospective location wouldn’t work.

“If that ends up being in your neighborhood, is that something you could feel comfortable with? It feels like our community said ‘not now,’” Reynolds said.

One of the major advances made in the last year to address homelessness was opening Lincoln Place across from Share House. The apartment complex gave housing to 30 chronically homeless people. It cost $6 million, or $200,000 per unit, to build this type of permanent, supportive housing. Reynolds would like to replicate Lincoln Place when there’s funding.

Resident Donna Stacey agrees that would be a good idea. After being homeless off-and-on for 13 years, the 48-year-old moved into one of the microapartments with her dog, Karma. Her window overlooks Share House.

She understands people’s concerns about mess and said that people who are filthy make it worse for everyone.

“Some people are just disgusting. That’s a reason why all that got put into place,” she said.

On Nov. 23, 2015, Stacey got cited while camping with her portable shelter — a wooden hut on wheels that kept her safe. The shelter was donated to Stacey after she was severely beaten. When police approached her about unlawful camping, she thought her options were to leave the shelter and police would take it away, or to stay with it and get cited. She chose the latter.

“I’m still in trouble for that,” said Stacey, who was arrested on a warrant related to her unlawful camping citation. She appeared in court earlier this week.

She also acknowledged that the transition to being housed is a slow process. That means that addressing the community’s homeless problem is a slow, nuanced process, too. A soft-spoken woman who mostly keeps to herself, she said it still feels weird to be indoors.

Homeless advocates have hailed Lincoln Place as a much-needed type of permanent, supportive housing for people who, like Stacey, were most vulnerable while living outside.

Prop. 1’s promise

What people may take away from Vancouver’s problems is that the services and programs in place to bring people out of homelessness don’t work.

“We’re in a situation where these housing resources are not nearly enough to meet the demand,” Silver said. “I get asked by people sometimes, ‘Do we have any new strategies? Do we have any new approaches of how we could deal with homelessness?’ It’s not about new strategies and approaches. It’s not that complicated when it comes down to it. It’s like, we need a place for people to take care of their basic needs and we need resources to help them get out of that situation into housing.”

Silver said he is frustrated because there’s not enough funding for what needs to be done to play catchup or provide those immediate, basic services to everyone who needs them. He said the work that the Council for the Homeless does can feel isolating and overwhelming without enough resources.

However, a new funding stream just opened up that Silver said he believes will impact people at the very bottom, living outside. Earlier this month, Vancouver voters approved Proposition 1, an affordable housing levy that will bring in $6 million annually for seven years. Money will begin being collected in January, so people could see an impact from that fund midway through next year.

Homeless camping ordinance – by the numbers

- 150 citations have been given to 96 people.

- 37% of citations were given to women.

- 63% of citations were given to men.

- 48% millennial generation (born after 1980).

- 36% Generation X (1965-1980).

- 15% baby boomer generation (1946-1964).

- 1% Silent Generation (1945 and earlier).

- 72 – Age of the oldest person to be cited for storing personal property in a public place.

- 68 – Age of the oldest person to be cited for unlawful camping.

- 19 – Age of the youngest person, a woman, to get a camping citation.

- 19 – Age of the youngest person, a man, to be cited for storing personal property in a public place.

- 37 citations (or 39%) were given out before 9 a.m. The earliest ticket was given at 6:40 a.m. — 10 minutes after the legal camping time ends.

- 7 – The greatest number of citations given in one day. This day was Nov. 3, 2015, when the revised camping ordinance first began being enforced.

The biggest chunk of the money would go toward building more housing. That, Silver and Reynolds said, is the main problem. Even if a low-income household has a rental assistance voucher that buys down the cost of rent, Vancouver’s vacancy rate is so low that there are few places to use a voucher.

What’s more, the levy allows for the creation of housing that’s affordable to people with the fewest resources. It could be used to build a small apartment building, another sort of Lincoln Place model. There isn’t a lot of mission-driven housing in Clark County, but that could change, Silver said.

“Because it’s locally controlled money you don’t have those federal strings attached that drive up the cost of housing,” he said.

The proposition was modeled after a similar levy that passed in 2012 in Bellingham. Like Vancouver, homelessness is on the rise in Bellingham.

While nothing’s been fixed yet, Silver said, “This result makes me very hopeful about the community that we live in and that people here care deeply about their neighbors and their families and friends.”

Besides the money — $42 million in total — Silver thinks the passage of Proposition 1 tells Vancouver City Council and other local leaders that there’s a mandate from voters to do something about homelessness.

“That, I think, opens other doors. This isn’t the last policy that needs to be worked on,” he said.

Patty Hastings: 360-735-4513; twitter.com/pattyhastings; patty.hastings@columbian.com.

Housing market will contribute $8.2M from 2017 to 2019

The problems faced by the homeless service system are market-driven, not a result of interventions that don’t work, said Michael Torres.

And those interventions — the solutions — are costly. Torres is the program manager of Community Housing and Development at Clark County’s Department of Community Services.

Clark County has about $4.2 million annually that funds contracts with service providers such as the Council for the Homeless, Share, Janus Youth and Impact Northwest. It’s one of the bigger sources of funding in the local homeless system.

How the money is dispersed is based on careful research and vetting of programs that are proven to work, Torres said.

“The best investment in dollars is the one that leads to a change in outcome, that actually changes the condition a person is living in from homeless to not homeless,” Torres said. “Because if that condition doesn’t change, the good that comes out of that investment is limited.” The money fluctuates because it comes from real estate document filing fees.

From a $58 filing fee, $48 goes to the Homelessness Housing and Assistance Act and $10 to the Affordable Housing For All Act. So, funding reflects the housing market with a one- to two-year delay.

“Having more people purchase houses does help fund the homeless system,” Torres said. “But what it hasn’t helped us in is the things that drive homelessness — the cost, availability and access to housing.”

What’s more, $30 of the Homeless Housing and Assistance Act surcharge will lapse in June 2019, reducing the filing fee and the amount collected by counties for homeless services. The state Department of Commerce projects Clark County will collect $8.2 million between 2017 and 2019.

If the sunset clause is not extended or ended, then that amount would drop to about $3 million. The Washington Low Income Housing Alliance, an advocacy group, is asking legislators to extend or remove the sunset clause. “If we do not address the sunset, 62.5 percent of Washington’s homeless funding will vanish in 2019,” said Reiny Cohen, director of communications at the housing alliance.

Counties have to be able to make plans around whether or not they’ll receive funding, so that’s why the housing alliance is taking action now rather than later, Cohen said.

“In this environment with McCleary (a state school funding mandate) it’s going to be interesting to see what happens,” Torres said. In terms of what can be done sooner to increase funding for the homeless crisis response system, “there aren’t many avenues,” he said.

The county could spend money from the general fund, create a new fee or fund homeless services instead of some other government function. The city of Vancouver, for instance, started taking $125,000 per year from the general fund to support the day center at Friends of the Carpenter and also pay for trash services to have dumpsters next to Share House, the men’s homeless shelter.

“It’s a hard ask,” said Torres, adding that he’s glad his job is not to figure out where to extract more money. “Part of our focus is with those resources that we have, is there a way that we can make sure they are used with the biggest return per dollar in the system? What can we do so the system is as cost effective as possible?”

State initiatives to improve the efficiency of the homeless housing system include rapid rehousing, diverting people from the homeless system, prioritizing people who live outside and promoting different types of housing, such as supportive and low-barrier housing.

Program Coordinator Kate Budd said the big focus is on moving people into stable housing as quickly as possible and preventing them from returning to the homeless system. While Band-Aid services such as emergency shelters are important, too, they’re expensive and are a temporary solution to someone’s homelessness. “Our goal is to make homelessness rare, brief and not reoccurring,” Budd said. “We want to do that as cost effectively as possible and as quickly as possible.”

Patty Hastings: 360-735-4513; twitter.com/pattyhastings; patty.hastings@columbian.com