In an east Vancouver apartment too small for its five inhabitants, Ginger Marcom is experiencing a brief moment of normalcy and even joy.

The 33-year-old single mother darts around the apartment, wiping down dishes, helping make dinner for her two daughters, her sister and her niece.

She looks exhausted. Her eyes are shadowed. But through it all, a tired smile warms her face.

Marcom lost her home of four years in July when her landlord abruptly sold the townhouse she lived in. Unable to afford her own place in today’s rental market, she’s been doubled up in small apartments since. But at last, some good news: Marcom’s name was pulled for a Section 8 housing assistance voucher, meaning she and her daughters — Kaylynn, 12, and Emily, 10 — could soon have a home of their own.

“They can have their own space,” Marcom said, days after receiving the good news. “Their own everything.”

Marcom’s story is one of hope, of services working as they should and of support systems rising to protect vulnerable families. But for every story like Marcom’s, there are hundreds of other families working through homelessness.

Large school districts in Clark County report higher rates of homelessness — they say their families are “in transition” — than they did a year ago.

More than a thousand students between Vancouver Public Schools, Evergreen Public Schools and Battle Ground Public Schools are doubled up with other families, living in shelters, camping in cars or otherwise living without a home of their own.

Marcom’s daughters both attend Evergreen schools, where 576 students were reportedly homeless as of Nov. 4. On the same day last year, 518 students were homeless.

District officials worry what that means for students’ health and performance in school. Students are expected to focus in class despite being unsure of where they will sleep or when they will eat.

“Learning begins in the home,” said Melanie Green, supervisor for the district’s Family and Community Resource Centers. “But what happens if you don’t have a home?”

‘Taking care of your neighbor’

There’s a stack of beige reusable bags in Carmella Bender’s office at Endeavour Elementary School, where Marcom’s daughter Emily, 10, is a fourth-grader.

The bags are discrete, and for a reason. Bender, the outreach coordinator for the school’s Family and Community Resource Center, has stuffed macaroni and cheese and canned vegetables into the bags, to be quietly given to students whose families are short of food at home. Each week, Bender sends students from low-income families with five to 10 pounds of food.

Bender’s office is lit with warm lamps, contrasting with the harsh, fluorescent lights in the rest of the school. There’s a cozy couch in the small space, and a refrigerator chills food for students. There are similar offices at each Evergreen Public Schools elementary school, as well as at other schools across the county.

“I think a lot of time families don’t know where to go,” Bender said. “They’re comfortable in the school environment. It’s great to have a resource they can come to.”

Schools are on the front line of Clark County’s homeless crisis. District officials describe offering an often complex network of support for families, including transportation, access to job and housing resources, tutoring and clothing. Some of that is required by the McKinney-Vento Act, a federal law that compels districts to provide immediate enrollment to those students and provide them transportation to and from school regardless of where they’re staying. That means if a student is living in a different district, or even a different city like Longview or Portland, districts must provide transportation.

“If we can help with clothing, food, that helps that housing piece, too,” Bender said.

Other efforts have a simpler mission: helping families feel normal. That can mean offering classes on cosmetics to help moms prepare for job interviews or teenage girls for prom

“We do have a lot of people that really do watch out for each other,” said Lydia Sanders, family resource services coordinator for Battle Ground Public Schools. “There’s a lot of taking care of your neighbor.”

Endeavour Elementary School and Bender have made all the difference for Marcom, she said.

Marcom had been on the waiting list since 2012 for low-income housing, but it wasn’t until she became homeless and connected with the school that she was eligible to enter the lottery for Section 8 vouchers. The school has also helped with smaller things, like food, and a pair of shoes for Emily, who on a recent cold day came home wearing tennis shoes and socks after wearing flip-flops to school.

“They’ve been helpful,” Marcom said.

‘They keep me going’

Kaylynn Ward, 12, adjusted the barrel of her clarinet, tuning it before performing with the Cascade Middle School band.

But she keeps an eye on her mom in the audience, conscious — and not happy — that she’s trying to record the concert on her phone.

Her daughter’s preteen angst aside, it’s surprising that Marcom was able to attend this concert at all. She has been pulling extra shifts at the pharmacy in Milwaukie, Ore., where she works. It’s usually an evening shift, making this night off a rarity.

Despite everything going on around them, Kaylynn and Emily are active girls. At Evergreen High School next door, Emily is performing with the Endeavour Elementary School choir at the Eastside Choral Festival. Both girls are also in Girl Scouts — Marcom is the troop leader — 4-H, and they play baseball during the summer.

“I try to keep them active so they don’t get stuck in everything that’s going on around them,” Marcom said.

But the clubs and teams distract Marcom from what’s been a difficult year for her too.

“They keep me going, between all their activities,” she said.

Marcom said she was evicted in July after her landlord, whom she said could no longer keep up with the maintenance on the home, told her she had to leave.

While her daughters were at their father’s house for the summer, Marcom packed up the home and left in 10 days. She put most of her belongings in storage and moved in with a cousin. From there, the family crashed with a friend of Marcom’s and that friend’s cousin in a cramped three-bedroom apartment. Marcom and her daughters shared one bedroom — though Kaylynn slept in the closet to try to get her own space. After several disagreements, they moved to Marcom’s sister’s apartment, this one in walking distance of both girls’ schools.

'They’ve gotten a little more reserved. They depend on people they’re around. I’m like 'You guys need to be kids. You need to do things as kids.'' Ginger Marcom

Marcom, who sleeps in the living room with her daughters, hopes they find a home that will take their Section 8 voucher soon, but a tight rental market in Clark County has made it tougher to find willing landlords. The inconsistency has taken a toll on Emily and Kaylynn. They’ve changed, she said, becoming less engaging than they once were.

“They’ve gotten a little more reserved. They depend on people they’re around,” she said. “I’m like ‘You guys need to be kids. You need to do things as kids.’”

Things are looking up in other ways for the family. Marcom is finishing her high school diploma at Clark College. She plans to pursue a degree to be a pharmacy technician, hoping it will increase her earnings beyond the $12 an hour she makes now.

“Don’t give up,” is her simple advice to other struggling Clark County families. “Don’t give up.”

‘Housing market’

Andy Silver, executive director for the Council for the Homeless, admitted he sounds like a broken record — but he’s not going to stop repeating two words.

“Housing market, housing market, housing market,” he said when asked about the greatest factor contributing to increasing rates of family homelessness.

Soaring home prices and low availability aren’t news to anyone locally. That’s been the story dominating Vancouver housing for well over a year. It’s what prompted housing advocates including Silver to successfully ask voters to approve an affordable housing levy, slated to bring in $6 million per year for seven years to preserve and develop affordable housing.

But it will take time before the market begins to feel the impact of that and other policies designed to protect renters. In the meantime, Silver estimated the demand for Council for the Homeless’ services has increased by 40 percent in the last year.

Enlarge

Ariane Kunze/The Columbian

Stories like Marcom’s — displaced by one crisis — don’t surprise him.

“The amount of people who are potentially looking at homelessness based on one setback has just skyrocketed,” he said. “We always had people who were living on the edge.”

School officials echo Silver’s concern about Clark County’s ongoing housing crisis. Vancouver Public Schools reported providing services to 692 homeless students and their families as of Nov. 9. That’s up from 570 students on the same day last year.

Charlotte Pellens is a special services administrator, helping coordinate homeless services throughout the district — “a big mechanism to work on,” she said.

Pellens said districts have come under scrutiny for the amount of time and resources they dedicate to serving homeless students. But Pellens noted that students without a stable home, consistent meals or seasonal clothes are at a disadvantage in the classroom.

“I think what we need to keep in mind is we’re not trying to give these students anything more than a normal student would have,” Pellens said. “We’re just trying to equal the playing field.”

‘Think about the good things’

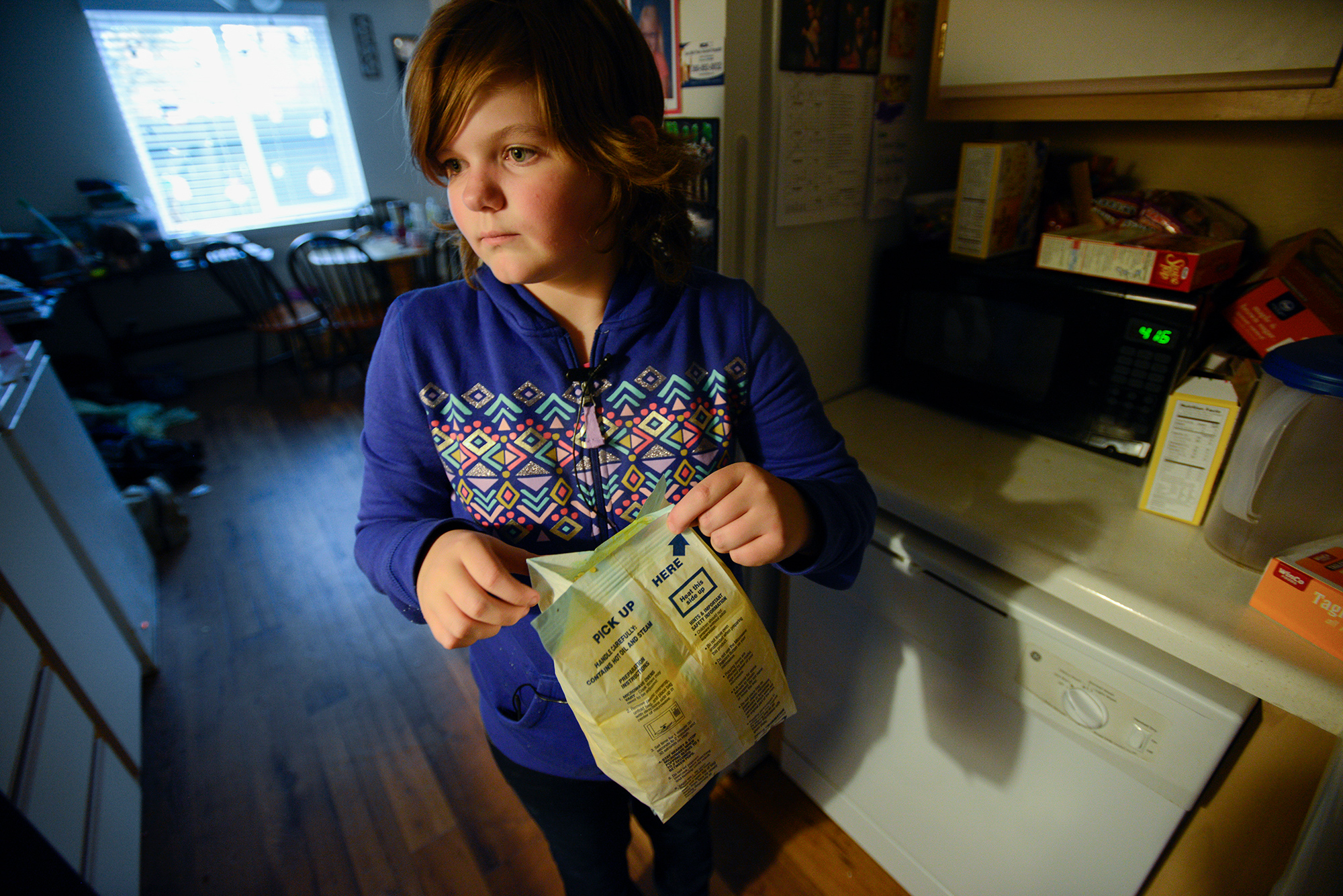

Kaylynn sets down a box of stuffing and bag of English muffins as she fumbles with the door handle to her aunt’s apartment.

“Sometimes it takes two hands,” she mumbles as she struggles with the key.

Kaylynn got the food from her school counselor, whom she’d asked if there was anything she could take to donate to her 4-H group’s food drive for a local family in need.

The English muffins are for her family.

“Sometimes we don’t have enough money after bills and getting stuff that we need … to get enough food for the month,” she said.

“I mostly try to not think of it,” she added. “I mostly try to think about the good things like having such awesome friends.”

“I mostly try to not think of (being homeless). I mostly try to think about the good things like having such awesome friends. Kaylynn Ward, 12

Kaylynn is the first one home today and most days. The apartment is empty and growing dark in the fall afternoon. She pops some popcorn, then plops down on the couch to watch the Disney Channel.

That’s the best part of this latest move in the seventh grader’s world: access to cable TV.

Kaylynn reveals her youth in some big ways. She wants an Xbox and a fuzzy, purple bedspread. She said she thinks her little sister is “sooo annoying” and her mom is too strict. When things are stressful, she daydreams of the princesses and heroines in her favorite cartoons.

“Sometimes I wish I was in those TV shows and movies,” she said.

But Kaylynn also has an acute understanding of what her family is going through. She speaks in detail about her mom’s challenges finding Section 8 housing. She worries about whether her mom will be able to afford furniture for their new home. She knows her mom is working many hours of overtime in order to provide for her and her sister.

But through it — bolstered by her friends, her school and the knowledge that better days seem to be coming soon — Kaylynn has hope.

“I try to see the light in things,” she said.

She makes the motion of going uphill with her arm.

“If things are bad, it will only go up from there,” she said.

Kaitlin Gillespie: 360-735-4517; kaitlin.gillespie@columbian.com; twitter.com/newsladykatie

Lack of transitional housing puts teens, young adults at risk

Michael Upp, 18, has some nerves about being back on the outside.

Upp was recently released from Daybreak Youth Services, and the last time he wasn’t in drug treatment, he was shooting up heroin in a bush in Bellingham. He has been homeless since he was 10, when he left home so he could better access drugs. His teen years were a blur of using and dealing heroin and other drugs.

“I’ve been locked up my entire sobriety,” said Upp, who went through treatment at Daybreak once before and also did a stint in juvenile detention.

In some ways, Upp is luckier than many teenagers who end up at Daybreak Youth Services, which offers rehabilitation services for teens with drug addiction and related mental illnesses. Because he’s 18, he’ll be able to sign a lease on a group home, helping him ease the transition into adulthood. Upp’s optimistic about what that means for his future.

“I try not to think about the past,” he said. “You got to be in the now. That’s what (Narcotics Anonymous) teaches you.”

But officials said Washington has a severe lack of transitional housing for teens who aren’t 18 and don’t have a home to return to, or teens who may be at risk of becoming homeless because they don’t have a safe place to go. A survey of Daybreak’s clients shows that about 1.8 percent are homeless, while a third report there are family members or others who use drugs in their home.

“There are so many of them that don’t have a safe, stable place to return to,” Daybreak Director Annette Klinefelter said. “So much of our staff time is literally spent trying to facilitate housing for these kids.”

Clark County Juvenile Court Administrator Christine Simonsmeier agreed that the lack of transitional housing for teens puts them at risk.

“We run into where they’re at end of sentence and for various reasons the parent is unavailable or isn’t ready to take the youth home,” she said.

One of Daybreak Youth Service’s goals is to develop a boarding school where students can live once they leave treatment — complete with continued counseling and rehabilitative services — until they are ready to be on their own.

“I’m working on it every day,” Klinefelter said.

— Kaitlin Gillespie