Coming up through the ranks as a Clark County sheriff’s deputy, Ric Bishop saw the same vicious cycle for countless individuals: they’d get arrested, placed in jail and land right back there after being released. Bishop recalled three ways inmates broke this cycle.

“They fell in love and someone cleaned them up and got them out,” said Bishop, who now oversees operations at the jail as the chief corrections deputy. “They got too old or matured out of it finally. Or they (died).”

In recent years, the jail has turned to offering inmates a fourth option: treating underlying substance abuse or mental illness issues that keep getting them in trouble with the law.

But that new option is difficult to offer in an old jail.

Last year, a consultant’s report suggested that the county’s jail is ill-suited to serve the county’s burgeoning population and adapt new practices aimed at reducing recidivism. The study suggested that the jail’s current condition could attract lawsuits if nothing is done.

“We need to have a conversation with the community about what happens in the jail,” said Clark County Council Chair Marc Boldt.

Boldt said that nearly 70 percent of the county’s budget is dedicated toward law and justice, taking up $208 million of the county’s general fund. He said the entire law and justice system hinges on a functional jail.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

“I think it goes to (the question of), what do we want the jail in our community to be?” said Jared Sanford, the CEO of Lifeline Connections, a local nonprofit that provides drug and alcohol recovery programs. “This old concept of locking people up and throwing away the key is not beneficial to the person. It’s not beneficial to the community.”

Boldt said that the other part of the conversation is cost. Upgrading the jail could cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and he isn’t optimistic about receiving money from the federal or state governments. In Clark County, bonds and levies for schools can face skepticism from voters. It could be an even harder sell to convince voters to raise taxes to improve a facility that houses criminals.

If no action is taken, the jail’s problems will get worse. The jail has launched a re-entry program that has shown some promise, but just as it’s taking off, it’s run into a barrier: the building itself.

Speaking at a recent work session, Clark County Sheriff Chuck Atkins said it’s no longer acceptable to keep inmates in overcrowded jails and confine people with untreated, serious mental health issues. Nor is it acceptable to delay, he added. If history is an indicator, a day of reckoning will come.

‘The building itself’

The Clark County Law Enforcement Center at 707 W. 13th St. is 124,318 square feet and two stories tall, filled with a maze of brick hallways bathed in unnatural yellow light. Hallways are periodically interrupted by hulking metal doors that echo when slammed shut, reminders of the highly restricted environment.

The air stinks of cleaning fluid and bodies in close quarters. Deputies say you get used to it.

When this jail opened in 1984, it solved a problem Clark County had spent nearly a decade working to resolve. Before it opened, inmates were jailed in either the lower level of the Vancouver police station or on the fifth floor of the county courthouse.

Beginning in the 1970s, articles began appearing in The Columbian describing the deteriorating conditions in the courthouse jail. It had become prone to fire hazards. Overcrowding meant first-time offenders were housed with hardened criminals.

A 1972 report said the county jail was beyond renovation. The next year, the American Civil Liberties Union criticized it as unsafe, having deficient medical care and lacking space to provide inmates with basic exercise and visitation.

“If we don’t build a new facility, the lid will blow off the old one eventually,” a Clark County probation officer was quoted as saying in 1973.

But in 1974, 57.5 percent of voters turned down a bond to finance a new jail.

The next year, the U.S. Department of Justice hinted that it would bring a lawsuit against the county over the jail’s conditions. By the 1980s, a consultant had described the jail as one of the worst in the country, and the sheriff had to turn away inmates. The facility had become so hot and crowded that inmates broke a toilet and other fixtures as they nearly rioted.

Finally, in 1981, the county commissioners awarded a contract to build a new 300-bed jail. The state paid $12 million of its $16 million cost. It opened in 1984.

Now, 34 years later, the county could be facing similar issues. After a handful of inmate deaths in 2012 and a fire that broke out in 2015, the county decided to take a hard look at the facility.

“There was a lot of concern about the condition of the building itself,” Bishop said. So the county hired design consulting firm DLR Group to check it out.

A mixed report

The DLR Group presented its study last year and suggested the county will be liable to lawsuits unless there are major upgrades. The report found that the existing building structure and enclosure are “fundamentally sound” and can provide a foundation for renovations. But it also found that much of the interior needs to be replaced, including the plumbing and electrical systems.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

DLR Group also found that the jail is ill-suited to keep up with the county’s growing population. Built with 300 beds, there were a little over 400 inmates in the average daily count less than 10 years after it opened. That rose to more than 700 by 2015. The study says the jail will need between 1,109 to 1,260 beds by 2036. The study also states the jail has experienced an increasing number of in-custody deaths, all but two of which were by suicide.

Remodeling the jail and providing those beds will be very expensive. The options for upgrading the jail outlined in a follow-up study cost $63 million to $284 million.

“The structure itself poses a huge problem,” said Kimberly Mosolf, an attorney with the jails project at Disability Rights Washington.

She said that jails are on the receiving end of the criminalization of mental illness. She said society over-incarcerates people who commit low-level crimes and suffer from mental illness. She said Clark County has the same problem and risks violating constitutional standards by putting people suffering from mental illness in solitary units during lockdown. In 2015, a judge ruled that Washington violated the constitutional rights of mentally ill people charged with crimes by holding them in jail for weeks or months while awaiting competency services. The current jail design prevents corrections deputies from adopting practices that provide better services and supervision to inmates, particularly those with behavioral health issues. Mosolf said that Bishop is receptive to her concerns and seems to understand the larger problems.

But there is only so much a good jail commander can do.

“He has a jail that doesn’t give him a lot of flexibility,” she said.

‘Whole different world’

Bishop remembers working as a deputy in the old courthouse jail. He recalled having to bring inmates pitchers of hot water and climbing the side of living units, using a rubber mallet to make sure the bars were secure.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

When the new jail opened in 1984, “It was a whole different world,” he said.

Bishop recalls the get-tough-on-crime era of the 1980s and ’90s when Congress passed laws setting stiff minimum prison sentences. In 1993, Washington voters overwhelming passed the country’s first “three-strikes” law, mandating a life sentence without release for all criminals convicted of three serious offenses.

When Bishop became corrections chief in 2013, practices had entered yet another world. As he rose through the ranks and picked up consulting work, he visited other jails and learned about jail re-entry programs through the National Institute of Corrections. He realized “lock ’em up” practices were not only expensive, they weren’t working.

“If we can get these people the tools they need, we can improve our community livability, we can improve public health, we can overall bring down the burden on taxpayers,” Bishop said.

After taking over the jail, he made Cmdr. Randy Tangen, his then work-release sergeant, his “re-entry sergeant.” Now, the jail has stepped up its programs that provide inmates a bridge from incarceration to the community. These programs connect inmates with mental illness or substance issues with treatment, and also help with job training or housing. Although the data is insufficient to conclude re-entry programs are affecting recidivism, it does indicate their potential.

Of 560 inmates who participated in a re-entry program in 2014, 244 were incarcerated in 2015, for a reincarceration rate of 44 percent. Of those 244, 79 percent were locked up for administrative sanctions or relatively minor offenses such as drinking a beer or visiting a friend they had agreed to avoid. The sheriff’s office only tracked reincarceration for this study period.

The programs could be expanded, but space is an issue.

"The biggest problem we have is we don’t have enough space to accommodate all the organizations that want to help.” Jail Commander Randy Tangen

Currently, the jail’s H Pod, which includes four rooms, is the only place where 40 organizations — including nonprofits, government agencies and others — can offer programs and services intended to help rehabilitate inmates.

“The biggest problem we have is we don’t have enough space to accommodate all the organizations that want to help,” said Tangen.

One of the groups offering programs in H Pod is the Southwest Washington affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Since 2014, it has helped inmates with mental illness better manage their condition, reconnect with family and find support groups, said Peggy McCarthy, the group’s executive director.

She said that her organization used to hold weekly psychoeducational classes for about 20 people. But due to space restrictions, the classes have been reduced to twice a month, even though demand is high enough to hold them multiple times a week.

“We have so many people here who really want to work with people in the jail,” she said.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Lifeline Connections has a $130,000 contract to provide jail transition services. Sanford, its CEO, said his organization’s staff serves about 150 inmates a year, providing them with mental health and substance abuse disorder assessments before connecting them with services. He said that the jail is cramped, and it can be a challenge to find locations to meet privately with inmates.

If the jail isn’t upgraded, Bishop said, it will steadily become so crowded that it will have to start sending inmates to other jails, as far away as Yakima or Benton counties. Both McCarthy and Sanford said that shipping inmates with behavioral or chemical dependency issues away from their support networks and local services would greatly hinder the county’s efforts to reduce reincarceration.

Very slowly

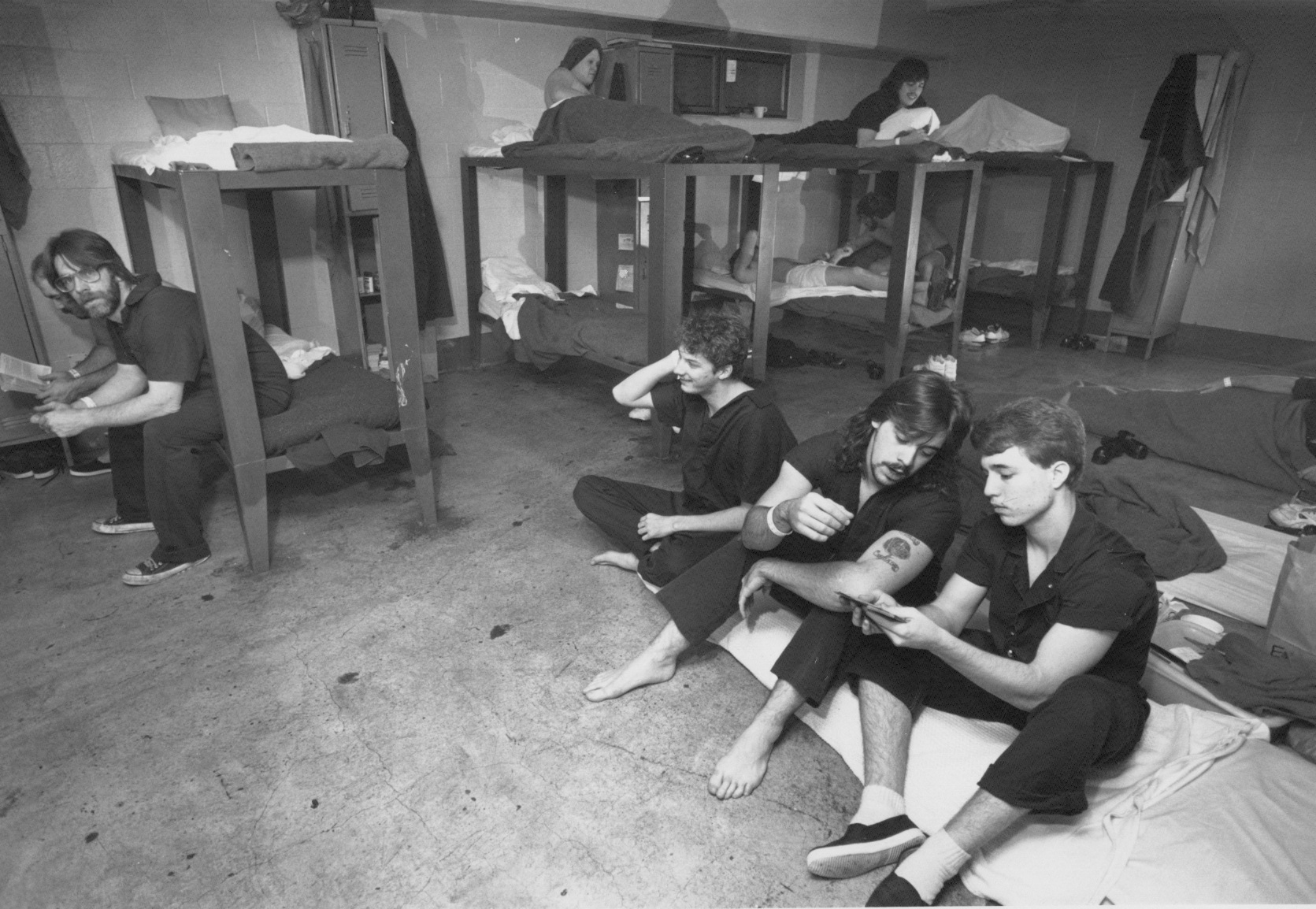

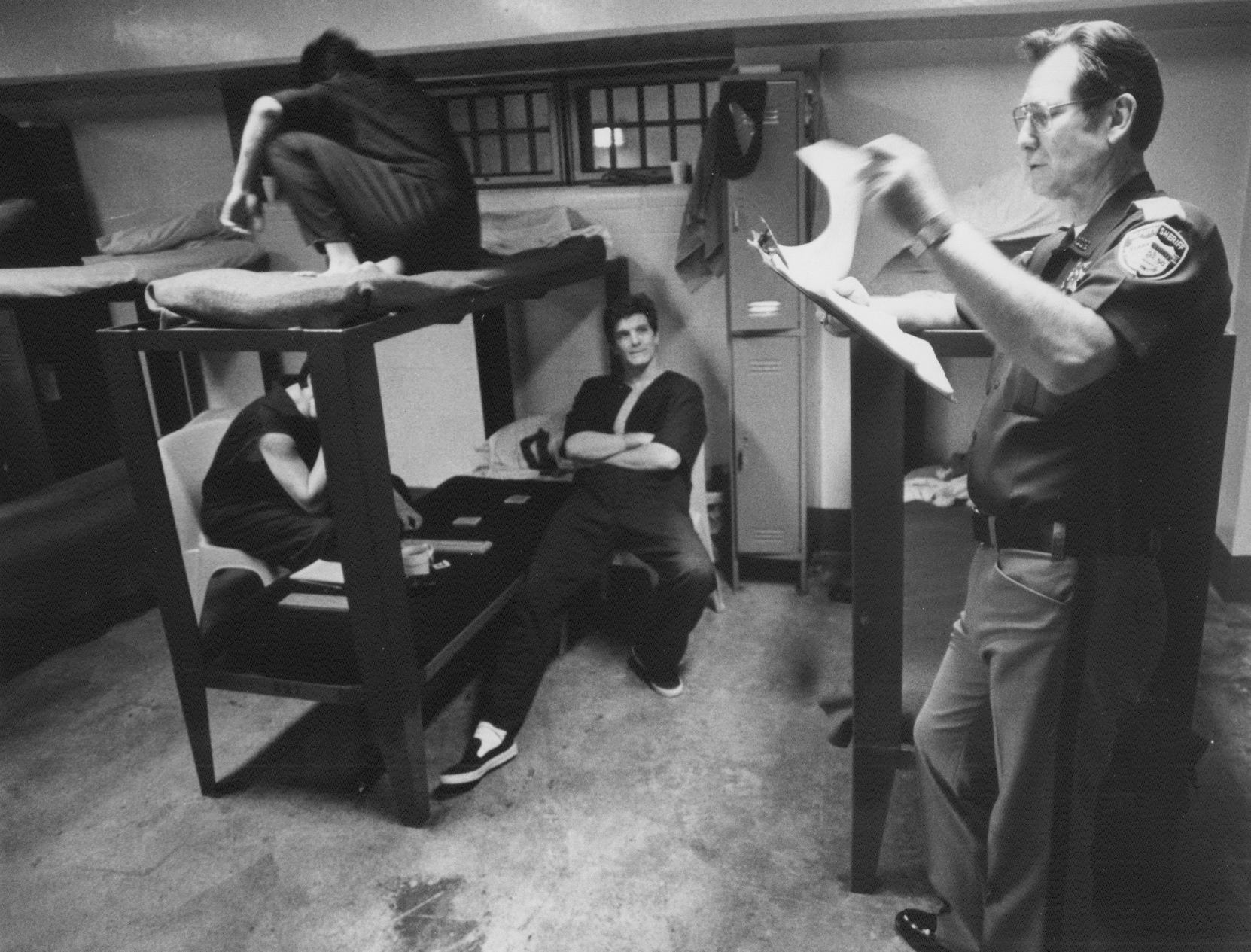

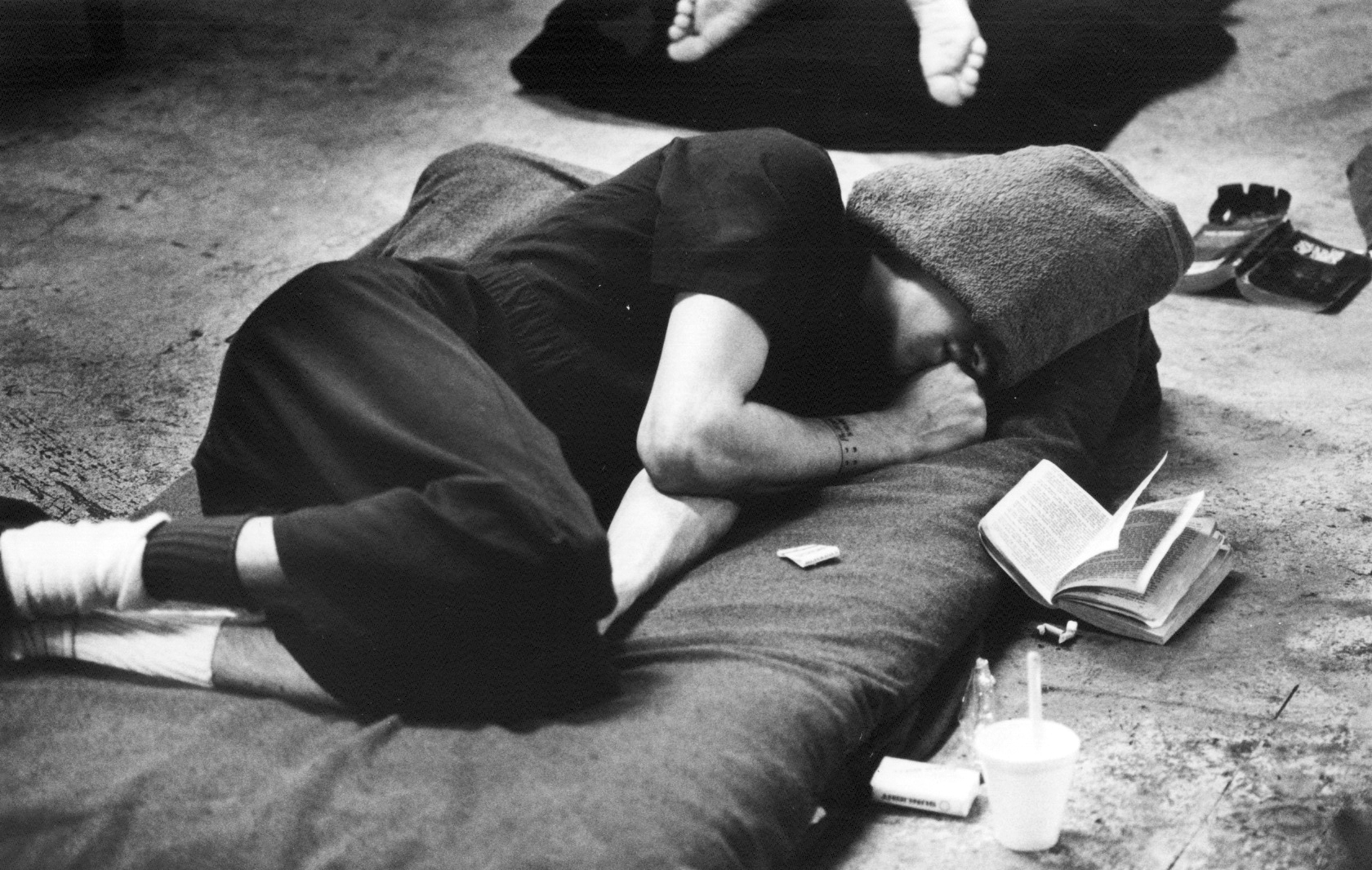

In the jail’s living pods, inmates mill about or recline on mattresses, some of which have to be placed on the floor. Deputies are separated from them by a hallway and observe them from behind transparent panels. It’s noisy. Doors slam, carts full of cleaning supplies rattle along, and the chatter of inmates is punctuated with an occasional shout.

There are 27 housing units and one multipurpose room. Getting inmates to meals, services, visits with their lawyer, family or a doctor requires deputies to escort them. Bishop said that he’s had to overcome the jail’s antiquated design with the efforts of his staff. He said that if the jail had more space, it would mean that inmates could be concentrated in one area where staff could more effectively supervise them and deliver services directly to them.

“The more you reduce people’s movement in a facility, the less staff is needed, so you’re working smart,” he said.

The first stop for inmates is downstairs, at the intake area. Bishop said the intake was originally designed to process 6,000 people a year. Now it processes 13,605 a year (who stay in jail an average of 19 days). He said that detainees need to be assessed to determine what brought them there and what services could keep them from coming back. But the medical and mental health units are upstairs. So booking is an unnecessarily slow, tedious process.

While Bishop speaks, a woman can be heard wailing in a cell. There are signs in Spanish, Russian and English advising detainees about medical care. A handcuffed man with sagging pants brought in by a Vancouver police officer sat in the garage awaiting his turn at booking.

The lack of space and delayed booking also slows down arresting officers, keeping them off the streets he said.

Katie Kauffman, an associate attorney at Vancouver Defenders, which represents indigent clients, said there are only four rooms for attorneys to meet with clients. She said there’s no way to schedule appointments, so she and other attorneys often have to wait for hours.

She said that she’s had clients in jail who couldn’t get pre-trial evaluations due to the lack of space, which has caused delays in court.

Studying the options

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Ned Newlin, the jail services liaison for the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, said that Clark County’s jail problems aren’t unique. Many of Washington’s jails were built about the same time as the Clark County Jail, because the state had made money available. Since the money went away, only a handful of new jails have been built or remodeled.

“So there hasn’t been a lot of building unless a local county decides to do it,” he said. Expansions are usually driven by overcapacity and funded by a sales tax initiative, he said.

The county is assembling a blue ribbon commission to evaluate its options with the jail. Boldt said that the county could go to voters with a bond to fund upgrades to the jail as soon as next year.

U.S. Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler, R-Battle Ground, has sponsored legislation intended to budget more money for mental health providers and inpatient beds, which could ease the situation at the jail. Boldt said that getting help from the federal government is a “sliver of hope.”

But in the meantime, Bishop will be doing what he can.

“I really am a person that believes in not repeating mistakes but learning from them,” he said.

Jake Thomas: 360-735-4515; jake.thomas@columbian.com; twitter.com/jakethomas2009