Afghan refugees in America face a convoluted, backlogged immigration system

It’s an understatement to call life in unstable, war-torn Afghanistan stressful. But for the fragmented Azizpour family, American life is proving stressful in new and different ways.

Chief among the family’s worries are immigration issues that are both complicated and all too common. Like tens of thousands of Afghan refugees who were rushed to the U.S. when the repressive Taliban regime swept into power in August 2021, the family has no assurances about staying here permanently.

The system for bringing refugees into the United States is underfunded, overwhelmed by multiple waves of global refugees and stymied by congressional inaction, said attorney Alma Jean, director of the immigration counseling and advocacy program for refugee agency Lutheran Community Services Northwest.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

The extended Azizpour family — Maryam, her two children, her brother and their parents — abruptly dropped their lives in capital city Kabul in August 2021 and endured a chaotic and violent journey to the airport, where they hoped to flee to Germany.

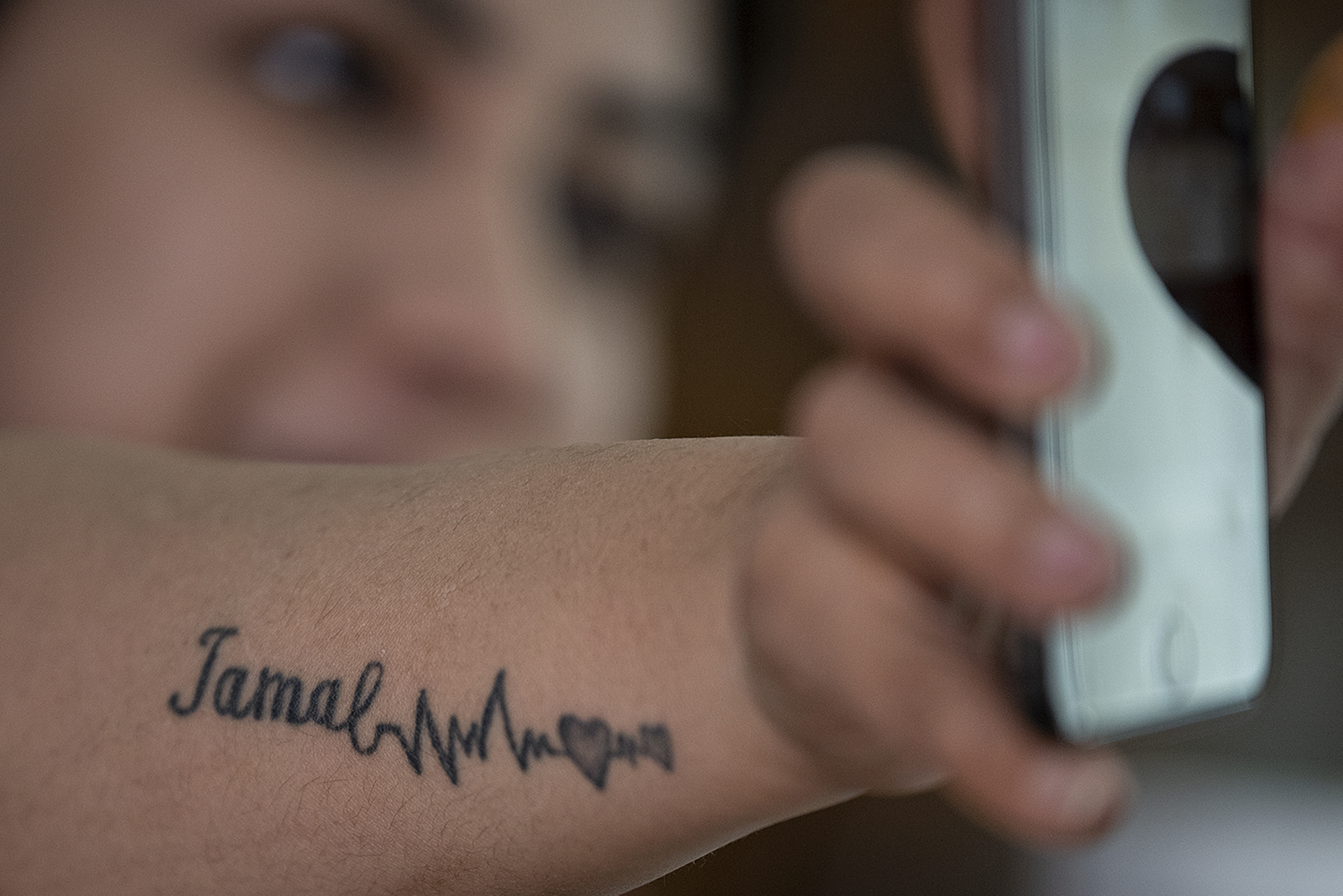

That’s where Maryam’s husband, Jamal Nasser Azizpour, went three years ago to earn a master’s degree. He hoped to pave the way for the rest of the family to join him and build better lives there. But the family was blocked from going to Germany. Forced to make a snap decision, they wound up in the U.S.

Work and school quickly absorbed Maryam and her family after they settled into the Hazel Dell area north of Vancouver late last year. But uncertainty about their immigration status, their future in America and any hope of Jamal joining them hover over the family like Pacific Northwest cloud cover.

“We are waiting a long time and we miss him very much,” Maryam said.

Afghan style

Maryam and her brother, Sajad Ibrahimi, 24, both emphasized that they’ve found Americans to be consistently friendly, patient and compassionate toward newcomers like them.

“The people in America are all really kind people. We appreciate those people who help us,” Sajad said.

When they first arrived in this area, the Azizpours were hosted for a few weeks by Wendy Ovall and her family in Felida, then equipped with everything a new home needs, from kitchen supplies to Christmas gifts, by members of the Ovalls’ church, Columbia Presbyterian. When the lease on that first unit ran out, Ovall helped the Azizpours score a similar place right down their Hazel Dell block. Ovall and other church friends also pitched in with cars and strong backs, helping the family make their move without hired help.

“We did it Afghan style,” Maryam said with a smile.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Star family

The Azizpour family’s dedication, energy and enthusiasm for assimilating into the U.S. has made a strong impression on Wendy Ovall.

“I think they are the star refugee family,” Ovall said. “Their attitude is: This is what we’ve been handed in life and we’re going to make the best of it.”

Other Afghan refugee families — those hewing to more conservative ideas about everything from strict religious observance to women working — may have a harder time fitting in and moving forward in America, said Matt Misterek, spokesman for Lutheran Community Services Northwest.

“There can be a cultural disconnect,” Misterek said. “These people have suffered so much trauma and they are trying to maintain their independence and their privacy. And they don’t speak the language. It can be very difficult to serve those families.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

‘Adversarial’

Uncertainty about the future still hovers over the Azizpours.

The Azizpours have what’s called “humanitarian parolee” status, meaning they were admitted in a hurry because their lives were in danger. It does not mean they are U.S. citizens or have permission to stay permanently. Humanitarian parolees are typically allowed a two-year stay in the U.S., said Jean, the immigration lawyer.

“The next step is applying for asylum … but that process is very difficult,” he said. Most humanitarian parolees are supposed to apply for asylum within one year. For most Afghan refugees in the U.S., that date comes due in late August or September.

After that, Jean said, the asylum interview and vetting process can take many months or even years. According to the Migration Policy Institute, more than 400,000 backlogged asylum cases were in the pipeline last year.

“As a legal advocate I’ve applied for asylum for refugees from 45 different countries,” Jean said. “For some the process took a couple of months. Some are still pending after seven years.”

Legal assistance for refugees is limited and based mostly on money granted by state legislatures, Jean said. Right now there’s more dedicated money for legal help for immigrants resettled in Oregon than those in Washington, he said.

But refugees applying for asylum without legal help is a recipe for disaster, Jean said, as they undergo “adversarial” interviews with immigration officials hunting for even the most innocuous reason to label someone a national security risk. If a desperate person ever bribed their way through a checkpoint in order to reach safety, Jean said, even that might be a sufficient red flag for rejection.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Waiting for Congress

Even less clear than the family’s immigration status, Jean said, is how Maryam’s husband, Jamal, can ever emigrate from Germany and rejoin his family.

Once Maryam secures permanent legal status, he said, she could apply for parolee status on his behalf. But Jamal would then join the flood of individuals applying for asylum and waiting months, or years, for an answer, which still could be “no.”

The best way to manage the crush of Afghan refugees would be congressional action, Jean said.

A proposed Afghan Adjustment Act would allow Afghan evacuees to apply for permanent status here after one year of parole, he said, and protect them from deportation. It would also provide avenues for processing and accepting Afghans stuck in other countries, like Jamal.

There’s lots of historical precedent for adjustment acts, which is how Congress has dealt with many waves of refugees from places like Hungary, China, Cuba, Vietnam and Iraq, according to the Migration Policy Institute. But some Senate Republicans have raised security concerns about Afghans who were hurriedly evacuated to the U.S. last year.

Action on the Afghan Adjustment Act stalled in Congress this spring. History shows that adjustment acts tend to become law no sooner than two years, and sometimes as long as five years, after a conflict has ended, Jean said.

The Azizpours remain in limbo. Maryam said she’s not sure whether to wait for legal help from Lutheran Community Services or add a private immigration lawyer to her family’s growing expenses. Jean told The Columbian he’s still not sure what to tell her.

“I’m happy my husband is somewhere safe, but it has been a very long time we have been without him,” said Maryam. “I think it is very complicated and I don’t know what will happen.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian