Afghan family endured a perilous journey from Kabul to the Vancouver area

Months after Maryam Azizpour and her family undertook a nightmarish journey through the violent streets of Kabul, Afghanistan, and fled the country, they’re still adjusting to peace and quiet in the U.S.

“Every morning is a surprise,” Azizpour said. “We open our eyes, and it takes two or three seconds to know we are not in Afghanistan. Everything is OK.”

Azizpour and her family are among 76,000 Afghans evacuated to the United States after Kabul fell to the Taliban in August, and among 144 resettled in the Vancouver area by Lutheran Community Services Northwest. The U.S. government taps the nonprofit to place and assist refugees in Washington and Oregon.

Whether fleeing Afghanistan last year or Ukraine today, refugees struggle to establish new lives in a nation that’s welcoming but still strange to them.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Now that Azizpour and her family are finding their footing in a Hazel Dell townhouse secured by Lutheran Community Services, Maryam is desperate to bring her husband here. Jamal Nasser Azizpour left Afghanistan in 2019 to earn a master’s degree at a German university, and hoped to get permission for his family to join him in Germany. He and Maryam wanted to get their children out of endlessly unstable Afghanistan.

Maryam fears the unthinkable might happen — that Jamal might be expelled from Germany and forced to return to Afghanistan.

Enlarge

Contributed by Maryam Azizpour

Normal, not normal

For two years after Jamal left, the rest of the Azizpours carried on with school, work and normal life in Kabul, a city of roughly 4.4 million residents and Afghanistan’s largest.

“We all had our busy lives,” Maryam said. “Kabul is the capital, and so, if you are living there, you will have a busy life.”

That ended last summer when the United States, which had occupied Afghanistan for 20 years, swiftly pulled out of the country.

The United States invaded Afghanistan in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C. The effort to topple the repressive Taliban regime and remake the country stretched into a decades-long war that cost thousands of military and civilian lives. The hard decision to abandon Afghanistan seemed inevitable to many Americans across the political spectrum.

But the manner of America’s swift, rushed exit from Afghanistan left chaos and peril in its wake, especially for Afghans who were connected to U.S. forces or who showed any evidence of a Western mindset. The Taliban regime that’s back in power is famously intolerant of women taking the tiniest steps forward into public life.

Even walking down the street without a male escort can get a woman into trouble with the Taliban, Maryam said. Worse still is behaving with real ambition: going to school, holding a job, choosing to stay unmarried and independent. (In recent weeks, the Taliban made what’s seen as a concession to international demands by opening a limited number of universities to women only.)

Enlarge

Contributed by Maryam Azizpour

“The day the Taliban arrived at Kabul, women could not go out, no girls were allowed to go to school, and women were not allowed to go to jobs where they work with men,” Maryam said. “If you are a woman alone, you cannot go shopping, you cannot go to the doctor. You must be with father, husband or brother.”

Maryam’s extended family — a well-educated, well-connected, progressive group — knew they were in danger.

“We were working with government offices and studying,” Maryam said. “Big problem for us.”

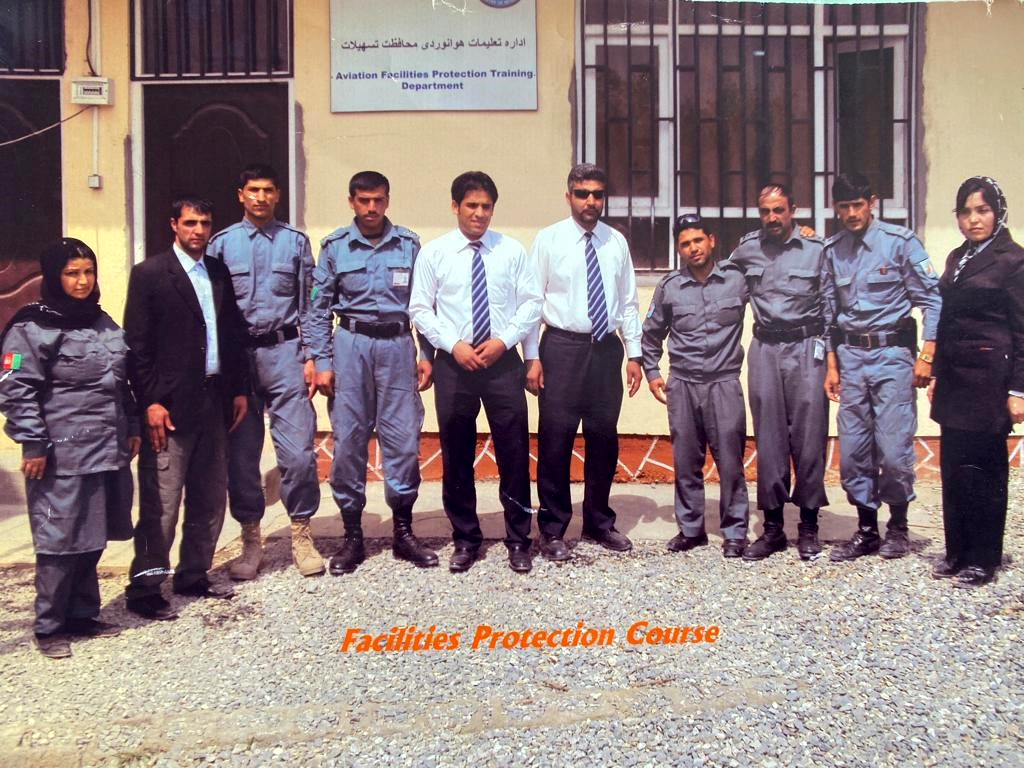

Maryam, 30, worked as a bilingual human resources officer and accountant for the Afghan ministry of foreign affairs. Her daughters, 10-year-old Marwa and 6-year-old Murwarid, attended their neighborhood school. Marwa was learning to speak a little English.

Maryam’s sister and brother — Fatema Noor, 26, and Sajad Ibrahimi, 24 — were both students at American University in Kabul. Fatema also worked for the Egyptian embassy. (Her husband, like Maryam’s, had already left Afghanistan and hoped to bring his family to join him in Philadelphia.)

Their father, Mohammad Ismail Rezayee, provided housekeeping and security for Americans working with the Afghan government. Their mother, Sediqa Rustami, held the most atypical job for an Afghan woman: She was an armed police officer.

Enlarge

Contributed by Maram Azizpour

“I loved my uniform,” Sediqa told The Columbian through Maryam’s translation.

“Before the Taliban, we had normal lives,” Maryam said. “Work, school, all the regular things of life.”

A normal life in metropolitan Kabul might not be recognizable to Americans who take peace and stability for granted. Terrorist attacks and bombings were a fact of life, including a notorious 2016 storming of American University, which Maryam’s sister and brother attended. Thirteen people were killed, including seven university students and one professor.

“You are scared to go out every time,” Maryam said. “Maybe your husband or family go to their jobs or school, and all the time you wonder: Will they come back again? Will an explosion happen in the road?”

Enlarge

Contributed by Maram Azizpour

Dangerous journey

As U.S. forces pulled out of Afghanistan in August, university students were notified that the Taliban had gained access to school data. Soon afterward, Maryam’s sister Fatema got a phone call from someone obviously posing as a university official who urged her to return to school.

Fatema called Maryam right away, and the sisters decided it was time to flee.

“We were 50-50 until we receive that call,” Maryam said. “Then we know we should leave.”

Maryam’s father tried his American connections but couldn’t reach them. Maryam’s husband, watching the collapse of Afghanistan from Germany, appealed to the German embassy to let his family come to him.

“We waited for the German embassy to do something for us, but they did not do anything, and we decided to go,” Maryam said.

Enlarge

Tribune News Services

The family knew reaching the airport wouldn’t be easy. Moving around on Kabul’s streets could be dangerous or even deadly, she said.

“If you are a woman, you should not leave your house. If they discover that you are a single mom, it’s very bad for you,” she said. “Taliban could say my husband is not living here and force me to marry another Taliban.”

Maryam and her children packed one bag each and hurried to Maryam’s parents’ home, where the whole family was gathering. Then they braced themselves for a perilous journey.

“We took a taxi halfway to Kabul airport,” Maryam said.

Halfway is where the taxi gave up. The roads were choked with thousands of people trying to flee.

Enlarge

Contributed by Maryam Azizpour

What’s normally a half-hour hop to the airport turned into a seven-hour nightmare, Maryam said. Five new checkpoints along the way created massive bottlenecks. Taliban soldiers harassed, beat and even shot people trying to flee the country.

“If the Taliban saw that you were walking with your papers, you give them your papers and they burn the papers in front of your eyes,” Maryam said.

All was chaos and danger, she said. “It was a rush of people. In front of you, thousands of people are moving forward; in back, thousands of people are moving forward.”

It was impossible for the large family group not to get separated.

“At the first checkpoint, I couldn’t keep my older daughter’s hand,” Maryam said. “She fell down, and many men fell down on her. I thought she was about to die. Everything was horrible.”

Maryam found her way back to her daughter “by some miracle,” she said. “My kids were crying, saying, ‘Let’s go home.’”

But there was no way to turn back and nothing to go back to, she said.

Maryam’s father, Mohammad, said a gun was held to his head during this ordeal. Later, Maryam noticed bruises on his body from being beaten with a belt. Amid all the other trauma, he didn’t even remember that happening, he told her.

Enlarge

Contributed by Maryam Azizpour

Snap decisions

Finally, the family reached the section of the Kabul airport where allied-nation officials were hurrying to handle the influx of desperate people, making snap decisions about thousands of human lives.

“They were asking all the people, ‘Where are you going? Is anyone working with Canada? Is anyone working with this country or that country? Does anyone have passport or visa for that country?’” Maryam said.

Although her family had connections with the U.S., Maryam was determined to take her daughters to Germany after two years of separation from their father. At first, her wish seemed about to come true. She and her children said their farewells to the rest of the family.

Then they waited. For hours. They crowded with others trying to get to Germany. They had no food. They begged officials for water and answers.

When the answer finally came, it was devastating. Germany would accept only people holding German passports. The same was true for many other European countries.

“Everyone was shocked,” Maryam said. “The girls were crying, and I was searching and searching for help.”

Enlarge

Contributed by Maryam Azizpour

Help finally arrived in the form of an American soldier who noticed the family, and an American official who heard her plea.

“He was a very calm, kind man,” Maryam said. “He fed us. He said, ‘I can take you to the USA. The future for your kids is brighter in the USA. They can do anything there. It will be a better life for your kids, and you can bring your husband from Germany.’”

Today, Maryam wishes she remembered that official’s name. She knows only that he was an older person, and a decision-maker.

“I owe him my life,” she said.

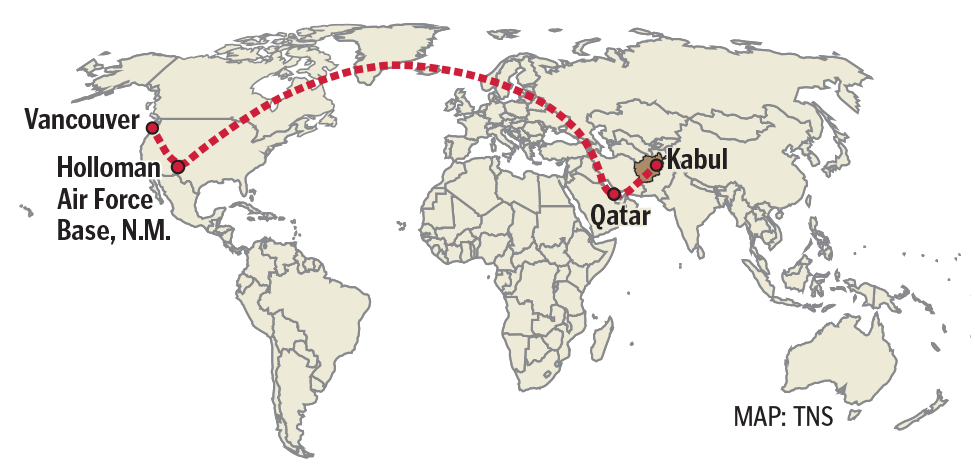

Eventually, Maryam and her children were reunited with the rest of their surprised family, and all boarded an airplane bound for an American base in Qatar. They stayed there one week. Then they flew to the U.S.

Enlarge

Contributed by Maryam Azizpour

Coming tomorrow: Afghan refugee family slowly making a life in Hazel Dell

Ukraine war sparks new wave of refugees coming to U.S.

Having just resettled thousands of Afghans in Oregon and Washington, Vancouver-based nonprofit agency Lutheran Community Services Northwest is now preparing to help an influx of refugees from Ukraine.

Over the past five years, the agency has resettled more than 2,100 people from Ukraine in this region, mostly in Tacoma, Vancouver and Portland. That work was ongoing before war broke out last month.

“The agency is already receiving Ukrainians who were in the resettlement pipeline for months or years — at least 200 individuals were set to arrive in the next several weeks,” according to a recent press release. “Now LCSNW also stands ready to assist those who are able to secure refugee status in the wake of (the recent) invasion.”

The agency is awaiting word from the U.S. government about a new wave of Ukraine refugees, according to spokesman Matt Misterek.

“It is our mission to continue welcoming those who face repression in foreign lands,” said agency president David Duea. “Our Vancouver district received 32 individuals from Ukraine in the first week of February alone. We will be prepared to welcome and serve.”

To learn how you can help, visit lcsnw.org.