Refugees in Clark County learn about pleasures, challenges of American life

There’s been precious little time for Maryam Azizpour and her family to slow down and take a breath since the U.S. military evacuated them from Afghanistan last year.

“You can never just take it easy,” the resettled refugee said of her new life here. “American life keeps you very busy and everything is very expensive.”

Rental assistance from resettlement agency Lutheran Community Services Northwest dried up after just a few months. The family’s short-term lease on an affordable rental in the Hazel Dell area north of Vancouver expired, forcing them to move to a unit with much higher rent. To cover their costs, all adults in the family have gone to work — even Maryam’s parents, who are just beginning to learn English and who, in other circumstances, would be nearing retirement.

Maryam Azizpour, 30, is raising two young daughters in the absence of her husband. Their daughters appear to have thrived this spring in the welcoming atmosphere of Hazel Dell Elementary School, but school is over now and the older girl, Marwa, must face another dramatic transition: moving up to middle school.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Most of all, Maryam is worried about the family’s ability to stay in the United States and reunite with her husband, Jamal Nasser Azizpour. Jamal left Afghanistan for Germany three years ago, intending to pave the way for his family to join him under something like normal circumstances. But when Afghanistan fell to the repressive Taliban regime last summer, the rest of the family was blocked from going to Germany and wound up fleeing to the U.S. instead.

The Azizpour family has done remarkably well remaking their lives in a few short months, but their future legal status here remains murky. They definitely don’t want to relocate yet again to Germany, Maryam said.

“We are loving this country more, day by day,” Maryam said. “Because we are happy here. We don’t have to be scared here.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

First year

Maryam is multilingual and used to work in accounting and human resources for the Afghan ministry of foreign affairs. Within weeks of arriving here, she started working as a translator for Lutheran Community Services, the nonprofit agency that works with the government to resettle refugees in this region.

Then she moved to a job as employment specialist with Partners in Careers, where she helps recent refugees like herself — some from Afghanistan but many more lately from war-torn Ukraine — get settled in the Vancouver area.

Her brother Sajad Ibrahimi, 24, was a university student in Afghanistan, studying civil engineering and aspiring to design buildings, he said. Now he works at Vancouver’s Frito-Lay plant and scoops up as many overtime shifts as he can, sometimes arriving for a 12-hour stretch at 3 a.m.

“The house rent is very high here. The health insurance payment is very high,” said Sajad, adding that health care is usually free or inexpensive in Afghanistan.

The Frito-Lay job, he added, “is OK. The people are really good, really friendly. They are cool people.”

But Sajad has pretty much foregone his civil engineering dream, he said.

“It’s too much to start again,” he said. “I need something easier that takes less time. We are dealing with payments.”

Rent on the family’s Hazel Dell townhome is $2,500 a month, plus utilities. Sajad said he would like to buy a home of his own someday, but there’s no telling when that might be.

Maryam and Sajad’s parents are also contributing to the family’s bottom line after landing restaurant kitchen jobs in downtown Vancouver.

All that hard work crowds out much time for the family to relax, Maryam said.

“I have no time to take them anywhere,” she said of her two young daughters.

“I don’t think (leisure) is a priority for them right now. What they need is to feel financially secure,” said family friend Wendy Ovall, who has lived overseas and hosted international visitors before. “For anybody who’s moved from another country, it takes at least a year before you can take a breath.”

Maryam and her girls did find time to attend Easter services and their first Easter egg hunt with the Ovalls, who have also taken them on occasional field trips to local attractions they’ve never seen, like Multnomah Falls and the Oregon Coast.

“We waited for sunshine for so long,” Maryam said.

Silly and serious

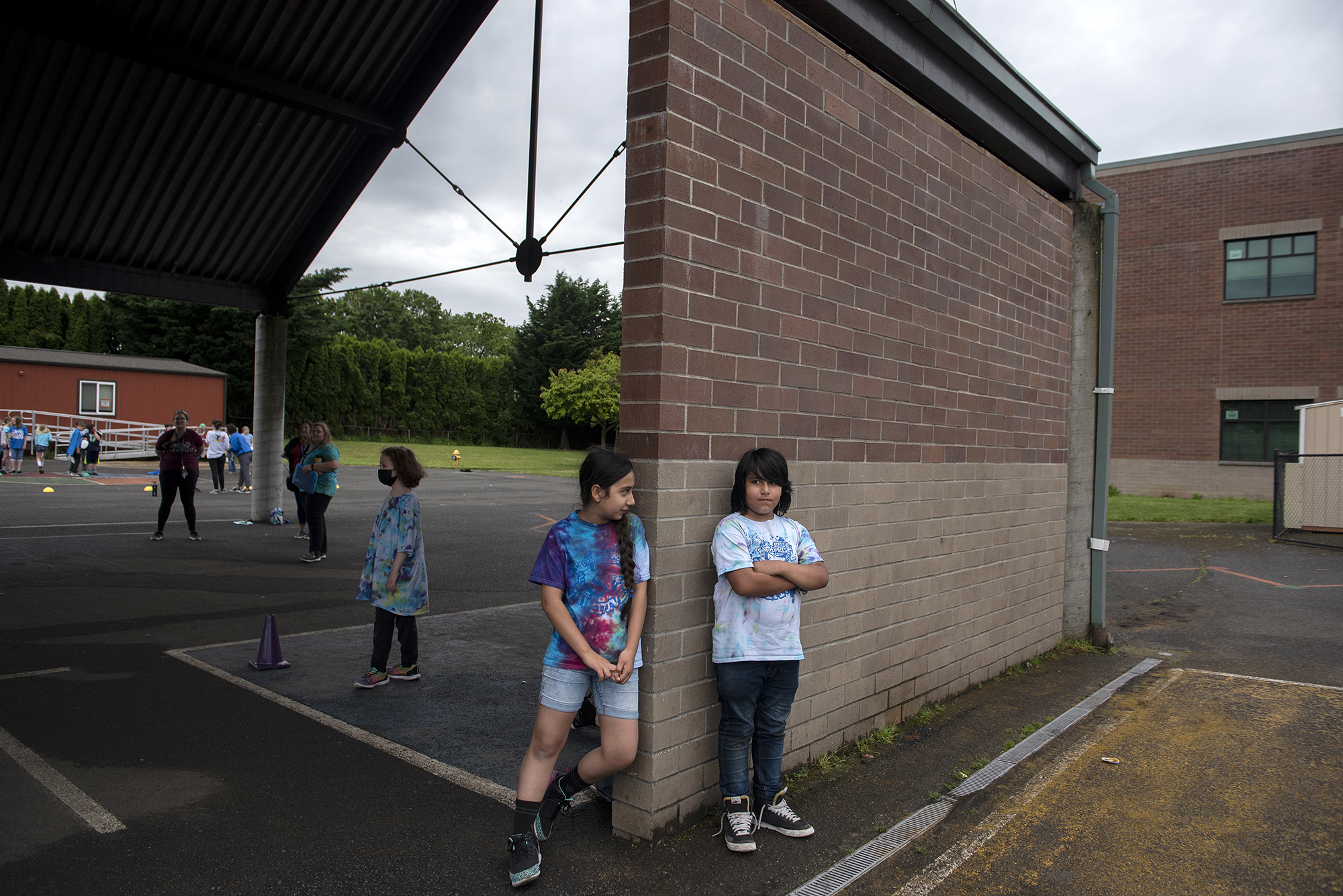

In the family’s transition to American life, the girls are adapting well.

There was nothing but glee on the face of Maryam’s youngest, 6-year-old Murwarid, as she played goofy games and tested silly skills — like hopping across the playground with a paper plate squeezed between her knees — during Hazel Dell Elementary School’s field day in June.

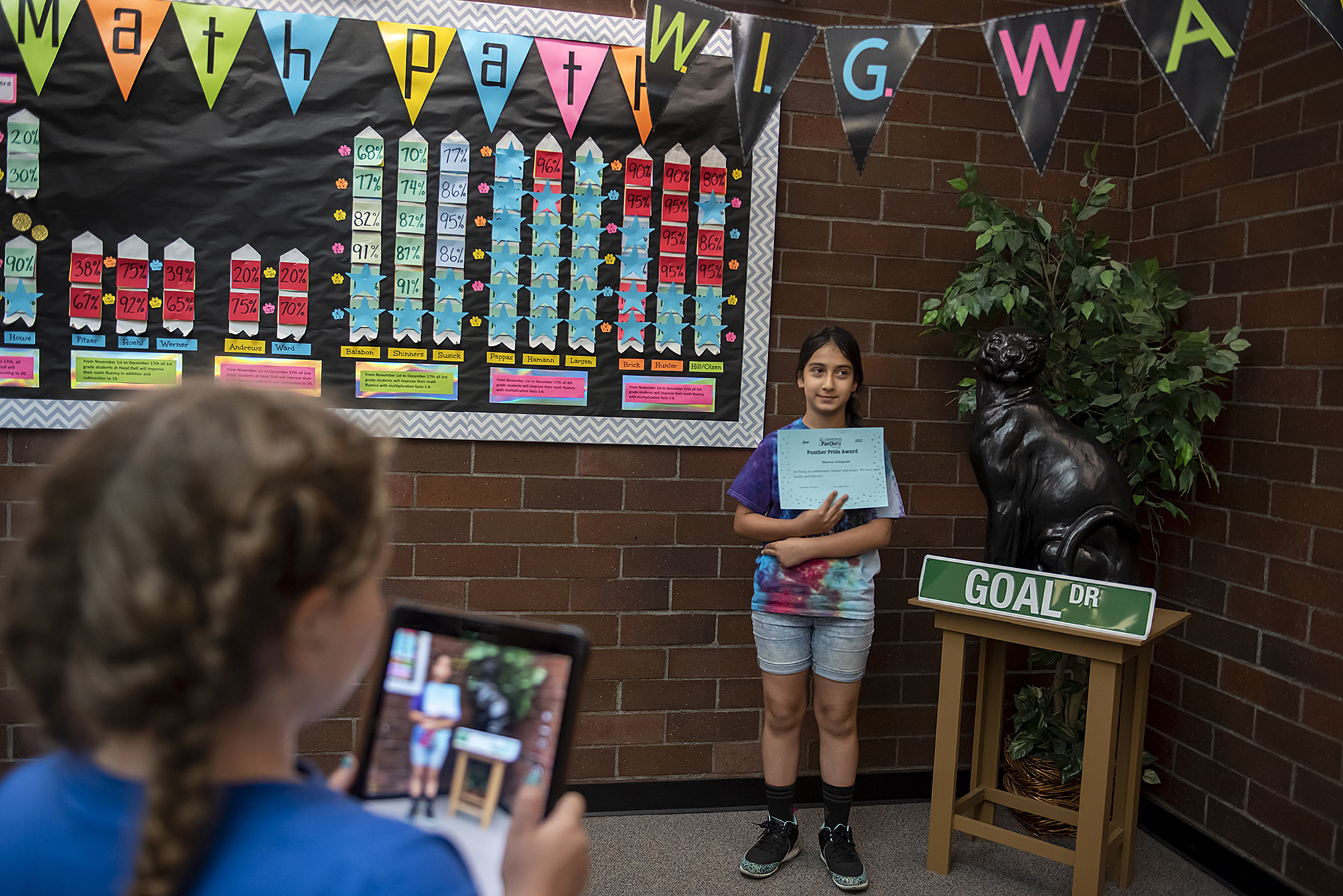

On that same day, 10-year-old Marwa won a school award for leadership skills, bravery and what teacher Joleen Brick described as a wicked sense of humor.

“She’s a hoot but she takes her education very seriously,” Brick said. “She knows how to ask for help. She also knows how to make it fun.”

The Taliban promised to allow women and girls in Afghanistan to pursue education, but reneged on the very day in March 2022 when schools were expected to reopen to all. Marwa hates talking about the Taliban and her family’s experience fleeing Afghanistan, when they endured violence and threats by armed soldiers in chaotic streets. Yet Marwa made surprisingly fluent English-language presentations about life in Afghanistan for her fifth-grade class, Brick said.

Marwa is “so kind,” Brick added. During her first week at school, Marwa spotted a peer who was alone and crying on the playground, and — despite her newness and limited English — immediately sought help from a teacher, Brick said.

Children who have moved from other countries naturally build empathy and compassion, Brick added.

“That’s something everyone needs these days,” she said.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

Many students at Hazel Dell Elementary grew up speaking another language, English language specialist Kasey Maloney said.

“Imagine what it’s like to be plopped in some classroom where the teacher is talking at grade level and you have no knowledge of what the teacher is even talking about,” she said.

To reach those kids, Maloney team-teaches in regular classrooms and also hosts a newcomers group, which emphasizes visual learning and call-and-response repetition of colors, numbers and other useful words like “backpack” and “classroom.”

“When (the Azizpour sisters) joined in January, it sparked a lot of excitement,” Maloney said. “I think everybody was fascinated.”

Their arrival inspired school staff to emphasize Hazel Dell Elementary’s unusually diverse student population, Maloney said.

“We found out we have students from 21 different countries,” she said. “Now we have 21 different flags up in the cafeteria.”

Continuing education

The Azizpour children aren’t the only ones pursuing an education in American life. Maryam’s father and mother, Mohammad Ismail Rezayee and Sediqa Rustami, have been livestreaming Clark College English as a Second Language classes at home. A local volunteer also hosts an in-person gathering of Afghan women to converse once or twice a week, Maryam said.

In the Afghanistan the family fled last year, Sediqa Rustami was a police officer, an unusual position of responsibility for a woman. Her husband provided housekeeping and security for Americans working with the Afghan government.

How would life have been for Sediqa Rustami under the Taliban regime? She demonstrated a little English for The Columbian: “Taliban. In house. No job.”

“I wish I could have come to this country earlier so I could have lived this kind of life and had opportunities,” Mohammad recently told family friend Wendy Ovall, she said.

While Mohammad tends to be soft spoken, his mastery of streetwise English emerges when he’s in the passenger seat of the used car Maryam bought soon after settling in, she said with a grin. Maryam said she often follows spoken directions from Google Maps and if she makes a mistake or takes a different turn, her father’s English-language corrections are quick and confident.

Men in the passenger seat while women do the driving is something all Afghans in America are still getting used to, Maryam said. Car ownership is much more universal here, she added. In Afghanistan, she said, only rich people own cars, and most others are accustomed to walking the streets.

But Hazel Dell neighborhood streets stay mostly quiet and empty, especially at night, Maryam observed. That’s very different than always-bustling Kabul.

“When we got here, it was very strange. No one is walking outside,” she said. “No one is in the streets. You don’t see people.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian