Afghan refugee family gradually learning about life in Hazel Dell

Before Maryam Azizpour and her family reached Clark County, they landed at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. Along with 5,000 other Afghan refugees, they underwent interviews, document processing, health checks and vaccinations.

Many of the refugees sheltered in plastic tents. Azizpour and her children were lucky enough to stay with a local family, she said.

When Azizpour, 30, fled her home in Kabul, Afghanistan, in August, she was hoping she and her daughters could join her husband in Germany. Jamal Nasser Azizpour, 36, has been living there for nearly three years and working to bring his family to the safety of that country. But amid the frenzied airlift of people eager to flee Afghanistan’s fundamentalist Taliban regime, Germany decided to welcome only Afghans with German passports.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Maryam Azizpour had little choice but to accept help from a U.S. official at the Kabul airport. She and her two daughters — as well as her brother, sister, mother and father — barely escaped to America.

Now that Maryam and her family are safe in a Hazel Dell rental, she faces another daunting task: to overcome legal hurdles so Jamal can join his family here.

“It has been three years, almost,” Maryam said. “We miss him very much.”

Enlarge

Baby steps

After about six weeks in New Mexico, Maryam and her family arrived Nov. 6 at Portland International Airport. Greeting them were officials with Lutheran Community Services Northwest, a nonprofit organization based in Vancouver that works with the U.S. government to resettle refugees here. (Maryam’s sister, Fatema, went to Philadelphia to rejoin her husband there. Like Maryam’s husband, he had left Afghanistan earlier, to try to pave the way for the rest of his family to get out.)

The Azizpours of Kabul now found themselves guests in the spacious Felida home of Wendy and Jeff Ovall, who are accustomed to hosting international exchange students.

“We’ve lived overseas, and I know what it’s like to be a foreigner in a foreign land,” Wendy Ovall said.

When she learned about the emergency in Afghanistan last summer, Ovall made some calls and found her way to Lutheran Community Services. She was advised to sign up with Airbnb’s Open Homes project, which offers shelter to people during emergencies.

When they first arrived at the Ovalls’ home, Maryam and her family spent a few days recuperating indoors. Then they started taking baby steps into a different world.

Enlarge

Photo contributed by Douglas McClay

“They started walking around the neighborhood, to the park, to the little market,” Ovall said. “We took them down to the waterfront. They were just amazed at how green everything is. They were really excited about how orderly things are.”

The Ovalls are “a very kind family,” Maryam said.

“Whenever they went somewhere, they took us — ‘You go like this, you go like this.’ They were helping us a lot,” she said. “At first we thought it would be difficult, but when we came here, it was just amazing.”

Nine-year-old Reed Ovall became best buddies with the Azizpour girls, 10-year-old Marwa and 6-year-old Murwarid, as they played games, listened to music and even burst into the occasional dance party, Ovall said.

“They played every day,” she recalled with a chuckle. “Our child is very outgoing, and I think he made them feel very welcome.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

New home

In December, Maryam and her extended family moved into a Hazel Dell townhouse that was made available through the goodness of the local property manager, according to Lutheran Community Services Northwest spokesman Matt Misterek.

The agency appreciates rental owners and managers willing to bend income and credit-check rules as well as reduce rent for refugees who are restarting their lives, Misterek said.

But guaranteed aid doesn’t last long, Misterek said.

“Intensive case management ends after 90 days, so the Azizpours are now done with it,” he said.

If more help is needed, refugees can sign up for an extended, yearlong program that offers some rental assistance and emergency funds.

“Many of our clients are connected with multiple community members who provide ongoing social support,” Misterek said. “The Azizpour family is connected with quite a few friends … who are helping them learn to drive, seek employment and provide social support as they continue to settle in.”

Enlarge

The family watches a television channel from Kabul, Afghanistan, via YouTube at their Hazel Dell home in Feburary. From left are Sediqa Rustami, Sajad Ibrahimi, Marwa Azizpour and Mohammad Ismail Rezayee. The family left everything behind when they fled Afghanistan last August, and all their furniture and household items were donated by new friends and volunteers.

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Wendy Ovall spread the word about the Azizpours’ needs through her church, Columbia Presbyterian. The congregation donated or purchased furniture, electronics, kitchen equipment and toys.

“People are very kind,” Maryam said. “American families have brought us everything. They brought us our first Christmas tree. They brought us so many gifts. People I didn’t know were knocking on the door saying, ‘These gifts are for the kids’ — games and toys, warm hats, warm gloves.”

Winter weather here is not especially different than in Afghanistan, Maryam said.

“The best are sunny days,” she said, sounding like a Pacific Northwest native already.

Enlarge

Photo contributed by Douglas McClay

Volunteers also have been helping the family navigate bus lines, banks, supermarkets and schools. Maryam’s daughters started attending Hazel Dell Elementary School in January. They’ve also been learning to ride bikes in the local park. Ten-year-old Marwa has gleefully taken up basketball at school.

“She is so happy to play basketball. That is something very new,” Maryam said. “If we were in Afghanistan, we would sit in the house.”

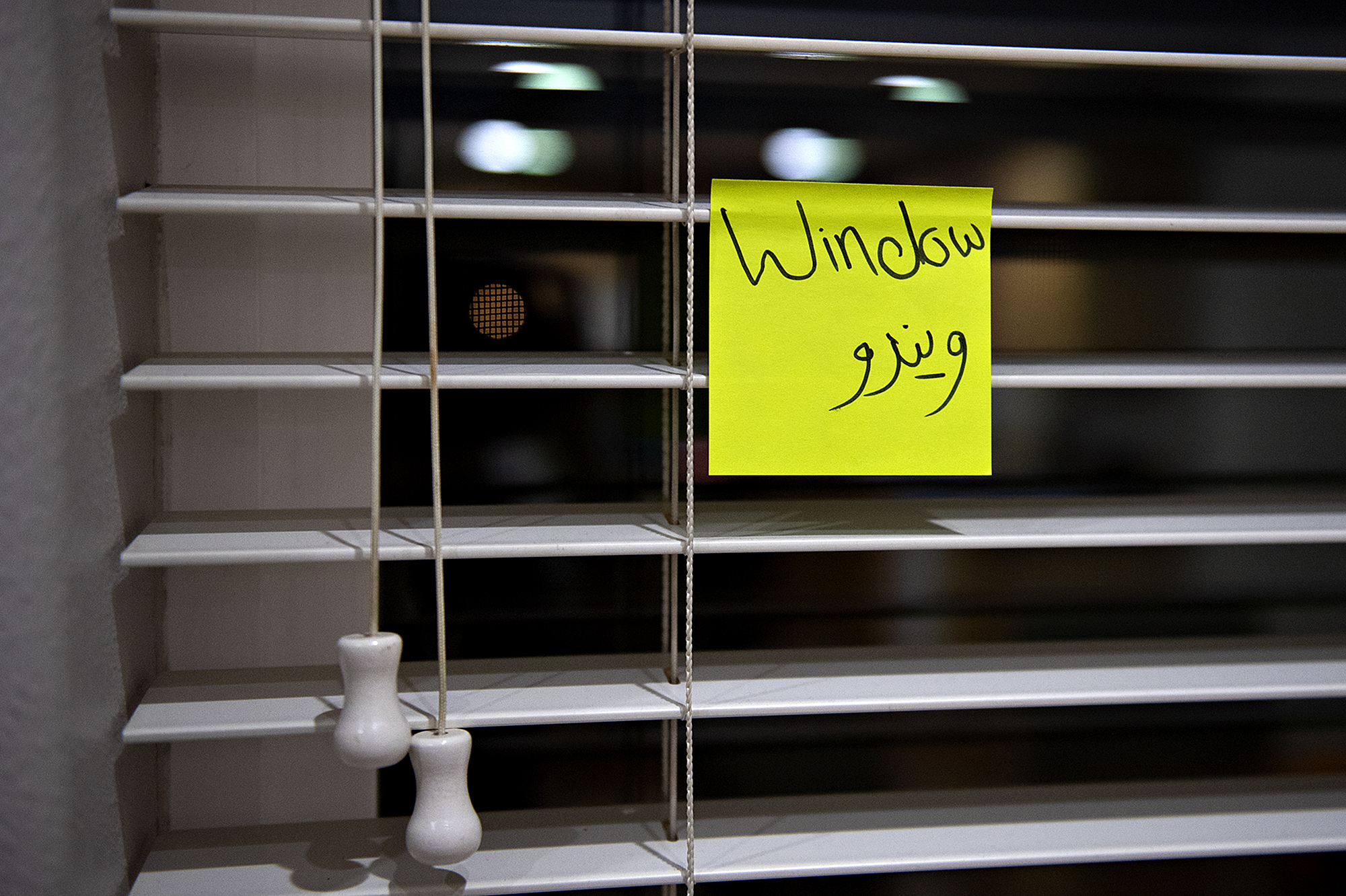

Yellow sticky notes bearing the English names of household items — window, table, tea — cover items in the family’s townhouse. Maryam’s parents are working on their English and taking walks to local markets and parks.

Maryam hopes they find new jobs or other purpose soon because they’re feeling a bit isolated and bored at home, she said.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Meanwhile, both Maryam and her brother Sajad recently scored jobs. Maryam — who speaks Pashto, Dari, English and some Hindi — has begun working as a translator for nonprofit job-training agency Partners in Careers.

“Now I am helping other refugees to find jobs,” she said.

Sajad started night shift work at the Frito-Lay plant in Vancouver. While he still aims to return to the civil-engineering studies he started in Kabul, for now his priority is making money, Maryam said.

Maryam and Sajad both have learner’s permits for driving. Think American traffic is bad?

“In Afghanistan, it’s much more crazy,” Maryam said.

Driving, shopping and doing other things in public are hard for women in conservative Muslim families, she added. At the Air Force base in New Mexico, Maryam said, she was aware of refugee wives whose husbands wouldn’t allow them to join others in the common dining area. They had to stay hidden away.

American-style personal freedom presents a whole new set of problems for those families, Maryam said.

“Our family is open-minded. We are not strict, so it’s easier for us,” she said.

The family includes practitioners of both main branches of Islam, Sunni and Shia, and nobody has a problem with women making their own way in the world, she said. Back in Kabul, Maryam’s father was a housekeeper and her mother was an armed police officer.

It’s still hard to believe how much their lives have changed in less than a year, Maryam said.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

Jamal in Germany

Now that Maryam has landed a job, she must find an immigration lawyer to remove the hurdles keeping her husband from leaving Germany for the United States.

According to Matt Misterek of Lutheran Community Services, the Biden administration made it unexpectedly difficult for Afghan refugees and their family members to get into the U.S.

Tens of thousands took the government’s advice and applied for entry through a little-used immigration option called “humanitarian parole.” The Wall Street Journal recently reported that a major bottleneck in the program means few Afghans have been admitted while tens of thousands have been denied or are still waiting.

On Jan. 20, 15 senators from Biden’s own party urged the administration to do more.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

“Following the fall of Kabul on August 15, the United States advised many of these individuals to flee to third countries where they were urged to apply for humanitarian parole into the United States. More than 35,000 Afghans did so,” their letter states. “With mounting reports of denials, however, we fear that the Administration is failing to protect the most vulnerable Afghans … and that thousands of individuals are at risk of falling through the cracks, despite their urgent and real fear of harm.”

Jamal’s problem appears to be that he’s not in any urgent danger, Maryam said. He left Afghanistan before things deteriorated in order to prepare an exit for his family. Now he appears to be stranded in Germany.

“It has been more than two and a half years. The kids miss him a lot,” Maryam said. “I don’t know what the problem is, but if I meet with a lawyer, I think there should be a way.”

Washington welcomes Afghan refugees

When a refugee family like the Azizpours steps off an airplane at Portland International Airport, it’s usually officials and volunteers with Lutheran Community Services Northwest, based in Vancouver, who welcome them with hugs, resources and companionship as they face the daunting prospect of restarting life in a strange new place.

The nonprofit is a regular partner of the U.S. government in placing refugees here. In recent months, the agency has resettled 144 Afghans in Vancouver and Clark County, 199 more in Portland, and 356 in the Tacoma area.

Washington ranks fourth in the U.S. for refugee resettlement, Lutheran Community Services Northwest spokesman Matt Misterek said, with 3,000 Afghans resettled here recently. That welcoming history began with Gov. Dan Evans during the Vietnam era and continues today, he said.

In recent years, Afghan refugee communities have grown up around the military bases where their American friends and associates live.

“There’s a nexus between the military and Afghan refugees, so many of whom worked as translators,” Misterek said. “They have friends and allies in and around the military bases here, like Joint Base Lewis-McChord.”

But resettling and supporting refugees is demanding work, he said. More volunteers are always needed.

“Our case managers and volunteers help with all kinds of refugee supports such as transportation, language tutoring, job training, school enrollment and health care appointments,” Misterek said.

But mental health help is not part of the package in Clark County, he added, even though it’s certainly needed by many refugees who have suffered violence and trauma.

“Unfortunately, we’re not able to provide them with behavioral health services in the Vancouver district at this time, although we do in Portland,” he said in an email. “We did offer some services from 2013 through June 2021, but had to cut them due to funding and staffing issues.”

There aren’t enough Afghans in Clark County yet to drive a “client base for culturally specific mental health programs,” he said. “Funding for our refugee adjustment support groups dried up for a couple years because the county didn’t issue a request for proposal during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The No. 1 priority for arriving refugees is finding permanent housing, Misterek said.

“Finding affordable housing options is hard enough for the average person in the Vancouver area. It’s compounded dramatically for refugees, who don’t have a work history or credit history,” he said.

“What we need most are rental managers, apartment owners and others who are willing to relax some rules.”

To learn more about how you can help, visit lcsnw.org.