Discovering an innovative newsman’s path into his and a family’s destiny

There’s an old machine tucked away behind a sliding gray plywood door at The Columbian, near a loading dock where beeping forklifts move massive rolls of blank newsprint.

I met my dad, Scott Campbell, there on a day in mid-April so I could see it.

He slid the door open for the first time in decades, and we both clicked on our flashlights to better see the massive cast-iron machine. Dust covered the hundreds of levers, sliding scales, handles and a typewriter-like keyboard.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

This machine, called a Linotype, is a relic of the newspaper industry, used when workers cast type out of molten metal to make up a page of newspaper.

“Can you imagine the intensity of this whole process?” Dad asked.

My great-grandfather, Herbert J. Campbell, used a machine like this in his days as a newspaperman. In the 1920s, he worked at the Portland Telegram, a now-defunct newspaper in downtown Portland, where he oversaw the workers who ran the Linotype machines.

There’s a story that runs in our newspaper family about Herbert. He noticed a problem with the intricate fittings of the thousands of tiny letters left small, one- or two-line gaps between the articles and the bottom of the text margins of the paper. Most newspapers filled them with a short advertisement, such as: “The Telegram delivered to your store, office or residence. 10¢ a week.”

It bothered Herbert to see those gaps. But he saw an opportunity in them, and it led him on an entrepreneurial journey to buy The Columbian in 1921, a century ago today.

I stood with Dad looking at the towering Linotype that he bought decades ago to display at The Columbian. It never panned out, but the machine meant too much for him to scrap; it was an echo of Herbert’s legacy.

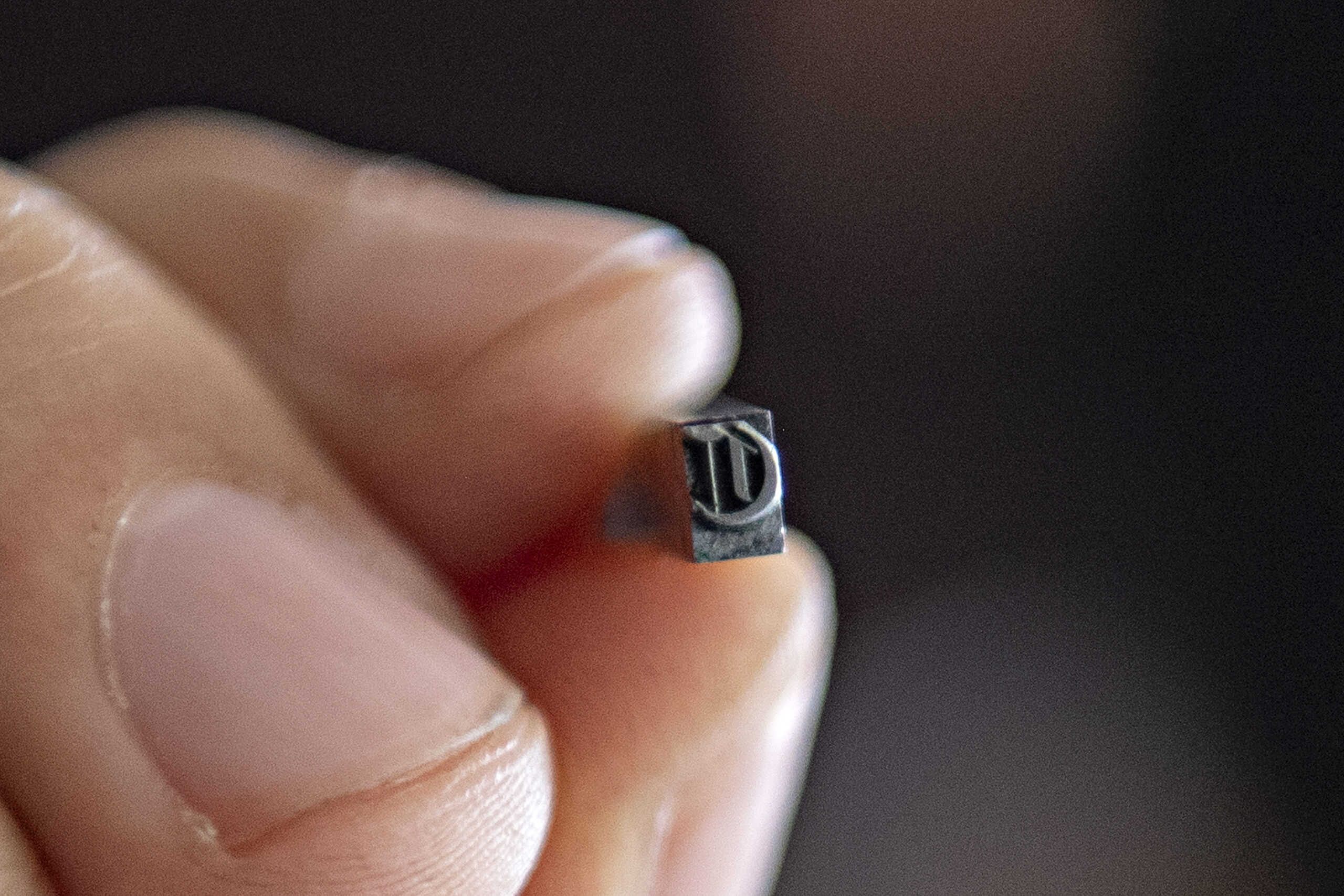

I climbed onto the machine to get a better look. I stuck my head in-between the dusty rafters to see it. In the cramped room, haphazardly arranged cabinets and containers held tens of thousands of tiny metal cubes with a letter at each end.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

In the rubble, I picked up a single piece with a letter “C” on the end — for Campbell, or Columbian, or both. I rolled it between my fingers and thought of how much our industry has changed.

I slipped it into my pocket. In the coming weeks, it would serve as a reminder as I retraced Herbert’s journey to buying the newspaper.

Herbert graduated from the University of Oregon in 1904. He reported for The Oregonian, and in his free time refereed football. He worked at the Portland Telegram, where he launched his lucrative side business idea. And finally, he settled in Vancouver as the owner, editor and publisher of The Columbian.

Each stop tells a piece of Herbert’s story, one that’s bound four generations of Campbell ownership to make this newspaper the best it can possibly be, and helping make Vancouver a great city.

It started with a few little metal pieces like the one in my pocket.

Enlarge

University of Oregon Libraries

The University of Oregon

I stood between a row of towering evergreens that line a walkway to Deady Hall, built in 1867, at the University of Oregon in Eugene. It’s one of the oldest buildings on campus.

At my desk at home in Vancouver, I have a framed black-and-white 1901 photo of this spot. In the photo, the trees, which now tower over me, were little more than saplings. A field takes up most of the frame.

Herbert surely studied within Deady’s walls.

Herbert Campbell was born in Carlisle, Penn., on Christmas Day 1882, and his family moved to Oregon when he was young. I don’t know much about why Herbert gravitated to journalism. His father, William P. Campbell, was a teacher.

Oregon didn’t have a journalism school back then, so Herbert studied English. English Professor John Straub, for whom the university later named a building, was a figurehead.

Somewhere close by the spot where I stood, Herbert ran into enough trouble to get him suspended from the department.

During his senior year, Herbert, 21, led a group of students to make a likeness of Professor Straub and hang it from a telegraph pole, according to a 1903 article in the Oregon Daily Journal. That act wasn’t uncommon then when people had disputes. Nevertheless, it is a blight in Herbert’s story. But it shows that Herbert wasn’t afraid of pushing the boundaries and challenging authority figures.

His classmates petitioned to get him back into their class, but the faculty forced him to repeat a year and switch majors. He graduated in 1904, a year late.

My family hadn’t heard of Herbert’s trouble until I began research for this story. Thanks to the help of Brad Richardson, director of the Clark County Historical Museum, I had access to digitized archives of dozens of newspapers.

Enlarge

University of Oregon Libraries

The archives let me cross-reference the spotty oral history and piece-meal documents about The Columbian’s history. But the Portland Telegram hasn’t yet been digitized. That’s the main reason I visited the campus: to find evidence of Herbert’s entrepreneurship in the microfilm archives.

A short walk away from Deady Hall, at a coffee shop near the Knight Library, I met with my friend Ryan Nguyen. Ryan is the editor-in-chief of the student newspaper, The Emerald, where I cut my teeth as a reporter while attending journalism classes too. (I hired Ryan when I managed the news team here a few years ago, and he’s worked his way up.)

I asked Ryan to look at some microfilm of The Portland Telegram to find some of the typesetting gaps that bothered Herbert. I also asked him to look at some pages from the year before Herbert left The Telegram.

Herbert’s invention lies somewhere in between those lines.

Enlarge

Creative Commons

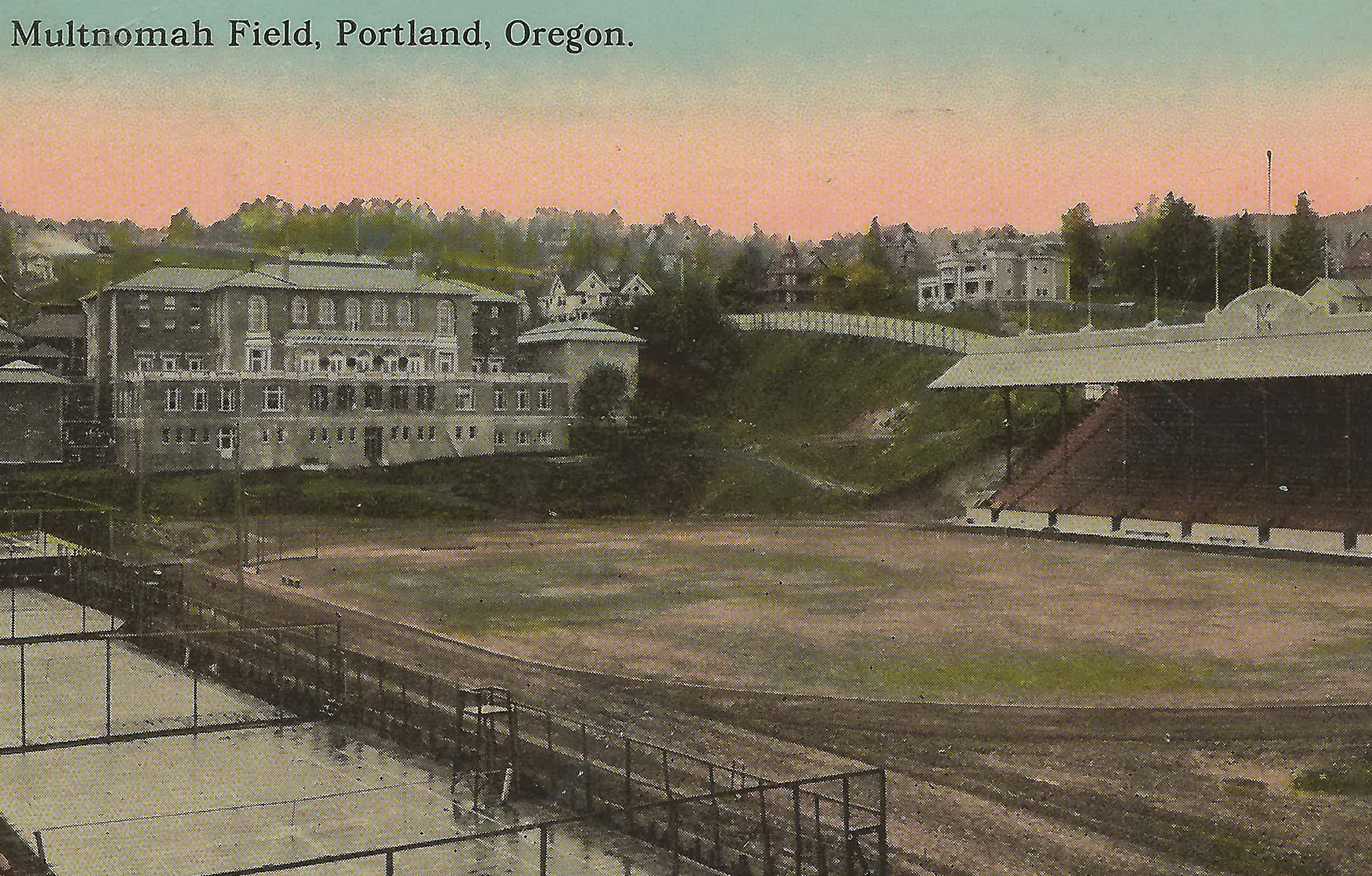

Multnomah Stadium

I sat in a green stadium seat and looked down at the greener patch of turf that covers the Portland Timbers’ Providence Park: one of the country’s most unique stadiums. A masked, socially distanced crowd cheered as the Timbers slotted in their fifth goal.

The historical stories of this stadium, sunken a few blocks below the street level of downtown Portland, are countless. Elvis Presley performed here in the ’50s. The legendary Pele played his last professional game here in 1977. In 1961, trucks dumped mounds of snow for a ski jumping contest. And twice the stadium has hosted FIFA Women’s World Cup games.

I’ve been coming to this stadium for more than 10 years as a Portland Timbers fan and have always appreciated its history. But while I searched through Oregonian archives for this story, I found a link to Herbert’s past here. The 1915 headline reads: “Umpire and referee named.”

Herbert graduated from the University of Oregon and moved to Spokane to work at the Spokane Chronicle. (Coincidentally, after I graduated from the University of Oregon in 2017, I joined the Spokesman-Review in Spokane.)

In 1908, Herbert became the “sporting editor” at the Spokane Chronicle. In 1912, he joined The Oregonian as a reporter, covering real estate and later writing about sports, including track and field.

“GREAT OLD COAST ATHLETES IN FORM,” reads the headline of one of his first sporting articles for The Oregonian.

Herbert wrote: “With the crack of the starter’s pistol half a dozen or so clean-limbed young athletes, trained to the very minute, will make a dash for the pole in the first race of what promises to be the greatest contest of track and field athletes ever staged on the Pacific Coast.”

It shows that Herbert could inject appealing prose into his stories that also carried weight: he was reporting on Olympic athlete and world-record holder Dan Kelly, who graduated from the University of Oregon. Kelly undoubtedly helped launch the school’s track-and-field reputation; a legacy that incubated the beginning of Nike at the campus in 1964.

When I read the old article in The Oregonian’s archives, “Umpire and referee named,” it uncovered a piece of Herbert’s past that no living Campbells knew: Herbert was the head referee – then called the “umpire” – for high school football games. The games were played on Multnomah Field, before a Multnomah Stadium was built around it. Herbert, according to the article, had “considerable experience as an official.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan of The Columbian

I reached into my pocket and grabbed the single metal piece Linotype with the letter “C.” I imagined a scene over 100 years ago as my great-grandfather, in a striped shirt, blew his whistle.

Herbert must have worked as an umpire largely on the weekends. Working in the newsroom was a time-consuming effort.

Blocks away from the stadium, in a building that’s now demolished, Herbert rose up the ranks in The Oregonian’s newsroom. In 1919; he took a new job at paper’s main competitor, the Portland Telegram, where his innovative spirit made him a small fortune, which allowed him to buy The Columbian.

Enlarge

University of Oregon Libraries

Portland Telegram

Chain-link fence borders the abandoned O’Bryant Square in downtown Portland, but that hasn’t stopped a few people from cutting it open and spraying graffiti on its bunker-like structures.

As I walked around the block to the below-ground parking garage entrance, I saw a sign that read “O’Bryant Square Garage is closed indefinitely due to structural safety.” I looked into the sky and imagined Herbert, a shorter-than average man, who wore round eyeglasses and a fedora, sitting at his desk in the Portland Telegram, which in 1919 held its office in The Columbia building on this block. (The building was demolished in 1972.)

Herbert was the paper’s news editor and assistant managing editor, leading a team of journalists to cover American troops’ return from the Great War. American industry picked up pace as the country entered the Roaring ’20s. Times were good. Portland supported roughly 100 newspapers and magazines.

Each morning, reporters from the 12 daily newspapers, including the Portland Telegram, scurried around the city chasing leads, tips and scoops. Toward deadline, they’d phone in a story to an editor or return to the newsroom to write their stories as the noise of clicking typewriters and cigarette smoke filled the air.

The edited stories would go to the Linotype operators to be set into blocks of type. Herbert oversaw this process thousands of times. That’s when Herbert thought about the gaps.

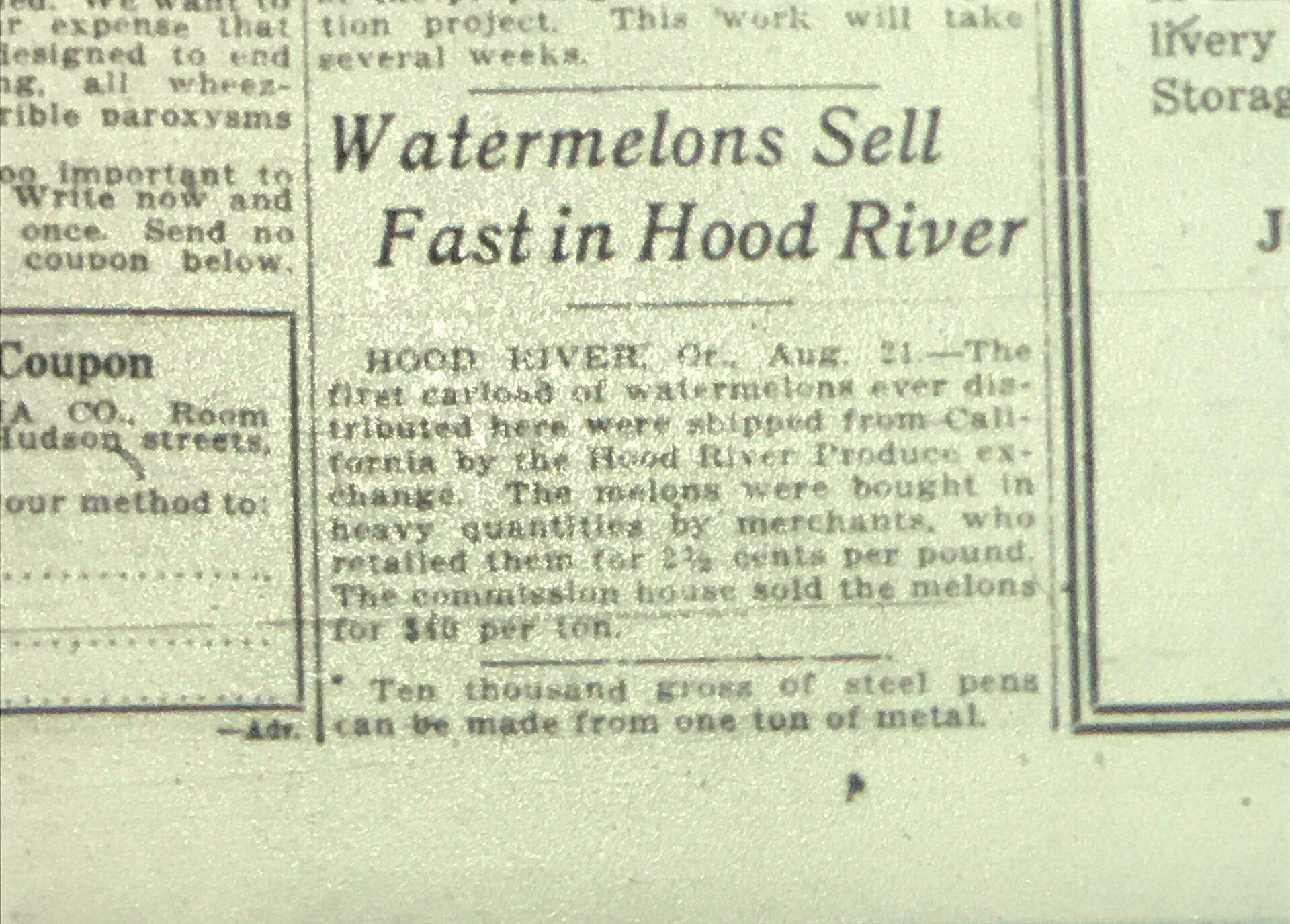

“My dad had an idea,” wrote my grandfather, Don Campbell, in a family memoir that he passed down. Herbert “combed the encyclopedias and compiled lists of trivia facts such as, ‘The tallest anthill in the world is 18 feet high.’

“When he had compiled hundreds of these facts, he had them set into type. This gave him a library of two-, three- and four-line fillers he could use to close up a page quickly under the deadline pressures. He hired a promotion firm to contact every newspaper in the United States and gave them a sample of these fillers – he called them ‘Campbell Liners.’ They signed up 1,000 newspapers, which was almost every daily newspaper in the U.S.”

Ryan sent me some pictures of these “Campbell Liners” that he found in the University of Oregon’s microfilm archives. One example from Jan. 12, 1920 reads: “A beaver does most of its work at night.” Another: “There are 14 bridges over the Thames in London alone.”

“This was such a good idea,” my Grandpa Don wrote, “that both the Associated Press and the United Press compiled their own lists of trivia facts and offered their own liner service to their members at no additional cost.

“In those days, newspaper managers were not very good businessmen, so they didn’t pay any attention to an expense of a dollar a week even though it was for a service they were already getting for free from the wire services.

“As a result, my dad continued to collect a dollar a week from a thousand newspapers. Postage then was 1 cent, and he had few other expenses, so this thousand dollars a week was almost all profit.”

Herbert never wrote down this story.

Of all the articles about the man, not one mentions the “Campbell Liners” or anything similar. Grandpa Don wasn’t alive when Herbert invented his Campbell Liners. The story was passed down by word-of-mouth.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

In 1921, with a small fortune saved, Herbert and his wife, Anna, traveled around Oregon and Washington. As they scouted prospective papers to buy, Herbert must have been looking more at the cities than the actual businesses.

One small town of about 20,000 caught his eye. Until about four years earlier, cars had to be ferried across the river to reach it. But in 1917, a brand new, two-lane bridge was opened.

The Interstate 5 Bridge made Vancouver an appealing prospect for growth.

Among the city’s multiple newspapers, one name reminded Herbert of his former office at the Columbia Building. The newspaper sparked his imagination as a place he could implement ideas like his “Campbell Liners.”

Enlarge

Clark County Historical Museum Photo Collection

The Columbian

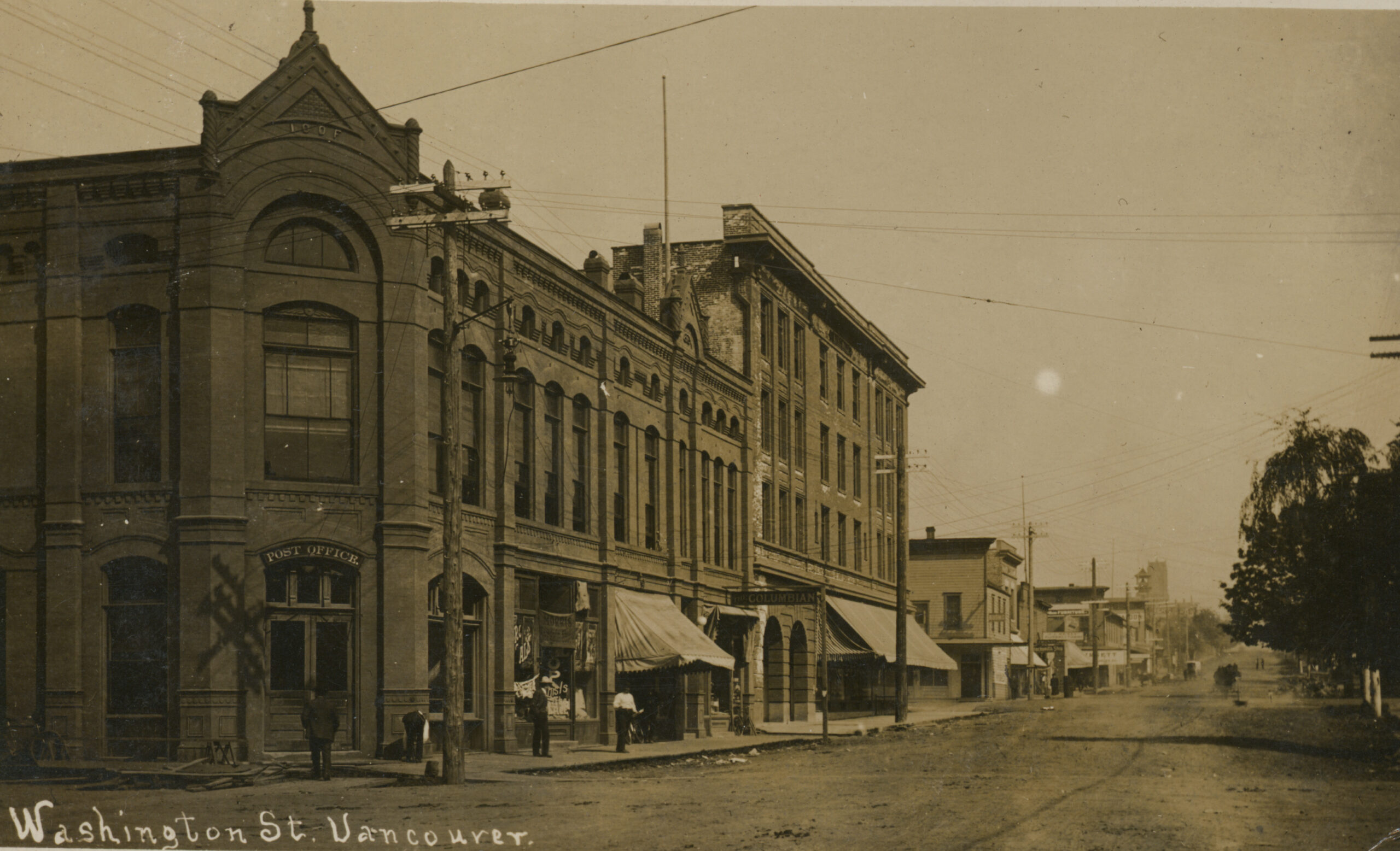

The clover of onramps to Interstate 5 and Highway 14 reach the other side of the road from where I stood, at an empty parking lot near Fourth and Washington streets. Boomerang Therapy Works occupies the sole building on that block, soon to be redeveloped into an apartment building.

About 100 years ago, Herbert drove his motorcar to the Interstate Bridge’s tollbooth, paid 5 cents, drove into Vancouver, passed the trolley stop on Main Street and parked where I stood.

The Evening Columbian rented part of the city’s post office building, a three-story, dark brick structure at that spot.

Herbert, 39, walked under the storefront’s white awning and hand-painted sign that read “The Columbian.”

He walked up the stairs to meet with The Columbian’s owner, editor and publisher, Will H. Hornibrook, in the cramped office space and newsroom. When the door opened, the aroma of black ink and molten metal wafted into the offices from the downstairs pressroom.

Herbert shook Hornibrook’s hand. The two men likely talked about how Hornibrook bought the paper in 1919 after serving as the U.S. ambassador to Siam (now Thailand) under President Woodrow Wilson. Hornibrook left Siam “because of ill health.” After returning to America, Hornibrook bought and operated the Albany Democrat newspaper in Oregon, then sold it and bought The Columbian.

Herbert J. Campbell bought The Columbian and all its equipment “for something like $10,000,” my Grandpa Don wrote in his memoir. “In those days that was a lot of money.” (Today, that would be about $150,000.).

There’s no other documentation of the sale that I could find.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

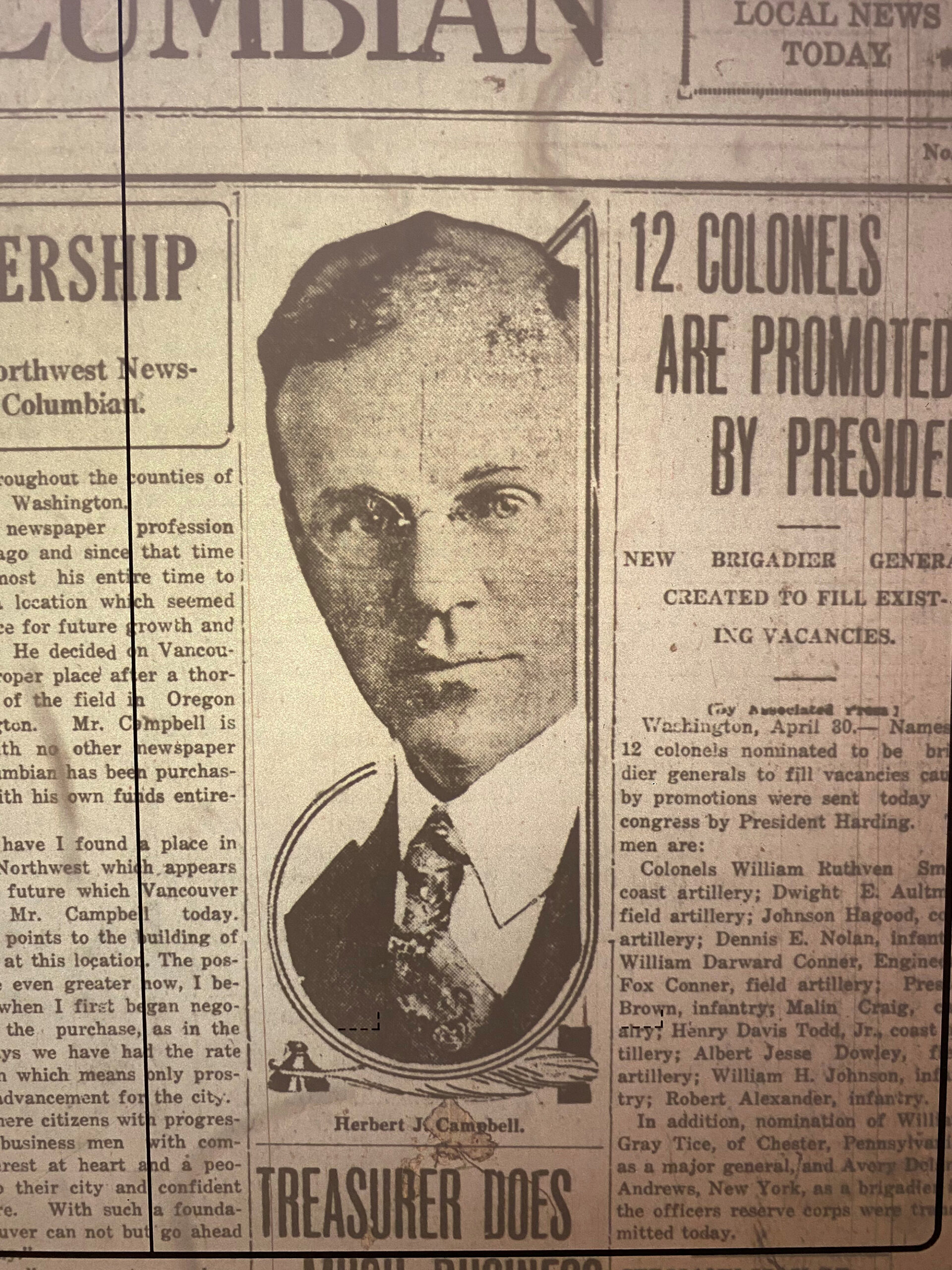

An article on Page 1 of the April 30 edition of The Evening Columbian shows a photo of Herbert in a black suit, high-collared white shirt and tie next to a headline that announces “CHANGE IN OWNERSHIP.” He looks serious and determined.

“Nowhere have I found a place in the Pacific Northwest which appears to have the future which Vancouver has,” Herbert wrote. “Everything points to the building of a great city at this location.

“The possibilities are even greater now, I believe, than when I first began negotiation for the purchase. I found here citizens with progressive ideas, business men with community interest at heart and a people loyal to their city and confident of its future,” he wrote.

“With such a foundation, Vancouver cannot but go-ahead to its destiny.”

So there I stood, staring at this empty lot. To my right, just west of that old green vertical-lift bridge that Herbert drove across, I can see the new Waterfront Vancouver buildings rising. It’s projects like these that Herbert must have envisioned.

I reached into my pocket and grabbed the metal “C” that I’d been carrying for the last few weeks. I could have kept this story going, because Herbert’s purchase of The Columbian was only the beginning. He accomplished amazing things and suffered greatly, filing personal bankruptcy during the Great Depression to keep the newspaper alive. He died in 1941 at age 58, while driving home from a meeting. He was survived by his two young sons, who would eventually pick up where he left off.

One of my favorite pieces that I discovered while researching this story was from 1913, during Herbert’s reporting at The Oregonian. According to the article, Herbert told a group of journalism students at his alma mater that “Newspaper work isn’t unlike other work. That is, the same qualities count for success as in any other profession. There is no quick or easy road to fame. But by hard work – intelligent hard work – there is almost no limit to the success the news writer may attain.”

I returned to that old Linotype hidden at The Columbian with my older brother, Ben Campbell, who is now the publisher of The Columbian. Looking at the outdated machine, I thought of the industry and leadership changes since Herbert’s time.

“If Herbert were here today, he’d be proud of all the things we’ve accomplished,” Ben said.

Ben and I work hard here every day, and we reflect about the business every evening. We’re picking up where our father, Scott Campbell, left off. Where his father and uncle, Don and Jack Campbell, left off. And where their father, Herbert J. Campbell, left off.

I took the piece of Linotype with the letter “C” out of my pocket and slid it into the machine, where, long ago, it could have printed one of the “Campbell Liners.” I thought of all the intelligent, hard work that our family must apply to this company, in Herbert’s prophetic statement, to reach the limitless success that we can attain.

I can imagine how intense this process will be.

Dear reader:

About 100 years ago, our great-grandfather, Herbert J. Campbell, purchased The Columbian newspaper. He chose to invest his life savings in Vancouver, he wrote, because here he found people with progressive ideas, a community interest at heart and “loyal to their city and confident of its future.”

Those fundamentals haven’t changed, but a lot else has. Vancouver’s population is roughly 130 times larger since Herbert took over, and the internet has shaken the financial foundation of the news business even as it has allowed more people than ever to read our articles.

Ben Campbell is now the publisher of The Columbian, Will Campbell is an editor, and Emily Campbell is assisting in community relations and organizing Columbian events. We are proud to continue Herbert’s legacy and will strive to make The Columbian the best newspaper and online news source it can be. Like Herbert, Don, Jack and Scott Campbell before us, we believe having a strong local media company is a pillar of the community.

Thank you to readers and employees who have supported our organization over the years. Your support is needed now more than ever. Our business faces new challenges as the information world becomes increasingly digital, a trend that the pandemic accelerated. We’re relying more and more on digital and print subscriptions, and less on print advertisements, to fund the company.

We are proud to be fourth-generation owners, but we’re excited to recently find out that we are the fifth generation of our family to work here: Herbert’s father was a stamp columnist for The Columbian. In December, the first member of the sixth Campbell generation, Jackson Lawrence Campbell, was born to Emily and Ben.

In the next 100 years, we plan to continue our family legacy for the benefit of our readers, employees and the Clark County community. We’re humbled and proud to steward this business that offers a critical service to Vancouver and Clark County.

Sincerely,

Ben Campbell and Will Campbell