Paul Harris and James Griener met on a crisp winter day in 1972 on the Brooklyn Heights promenade, a walkway overlooking the East River and the Manhattan skyline. They struck up a conversation and kept talking over gin-and-tonics. Griener was an actor in a play with the Mummenschanz troupe. Harris worked on Wall Street and watched the Twin Towers being built.

From the apartment they later shared in Brooklyn Heights, they could see the Statue of Liberty, the icon welcoming people to America “whose flame is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles.”

She’s in artwork and trinkets throughout the home they share today, tucked at the end of a long gravel driveway in the woods of east Clark County. She’s a nod to their life and love in New York City.

But for most of their life together, denied the right to marry, Harris and Griener felt exiled, someone or something-othered.

“I wanted what everyone else wants: the American Dream,” said Harris, 69. “I wanted to be recognized as the person who loves the person I’ve been with for 44 years.”

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

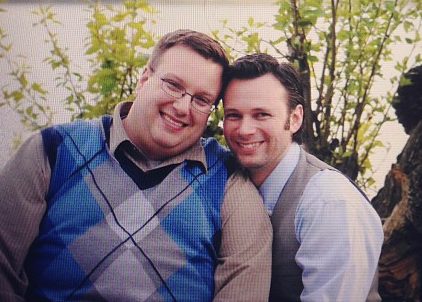

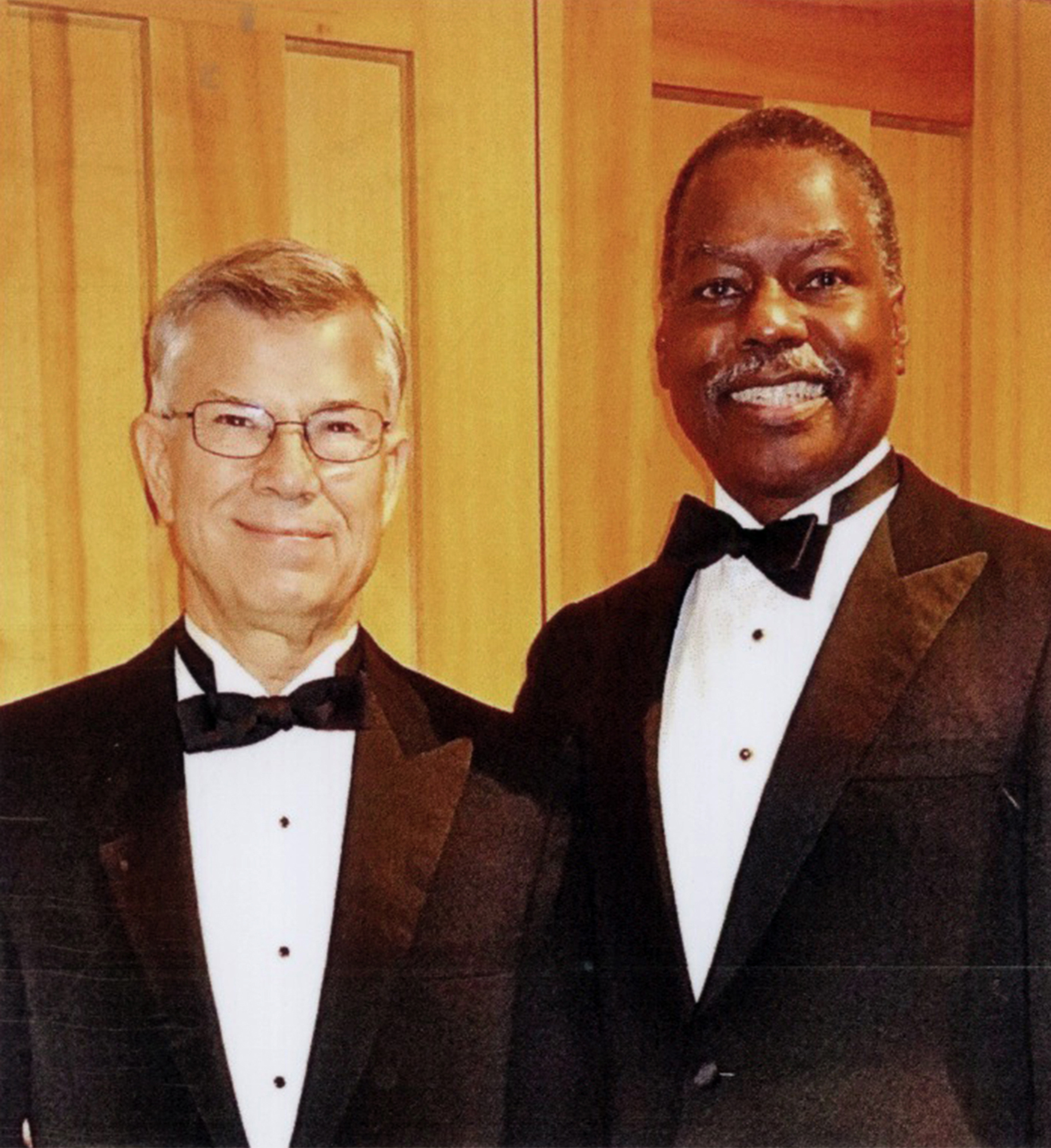

In two days, they’ll have been married five years. They said their vows at home Dec. 12, 2012, just three days after the first gay marriages could legally occur in Washington. Since then thousands of same-sex couples have married in Clark County and more than 17,850 statewide.

Harris and Griener wore matching tuxedos and invited a handful of people, including a friend who performed the ceremony. Till death do us part, they vowed.

By then, Griener was already retired from a career in technical writing. A few years later, Harris retired from working for the county. So, five years after legalization they’re living a quiet — quite boring, they say — life together.

“It’s interesting how undramatic it’s turned out to be,” said Griener, 73.

Their matrimony was a long time coming. They met just a few years after the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York where people clashed with police who’d raided a gay club. Now, the couple can enjoy all the rights and benefits that come with marriage. Even so, not all hearts and minds have been swayed by the change in the law, and there have been attempts to erode gay rights.

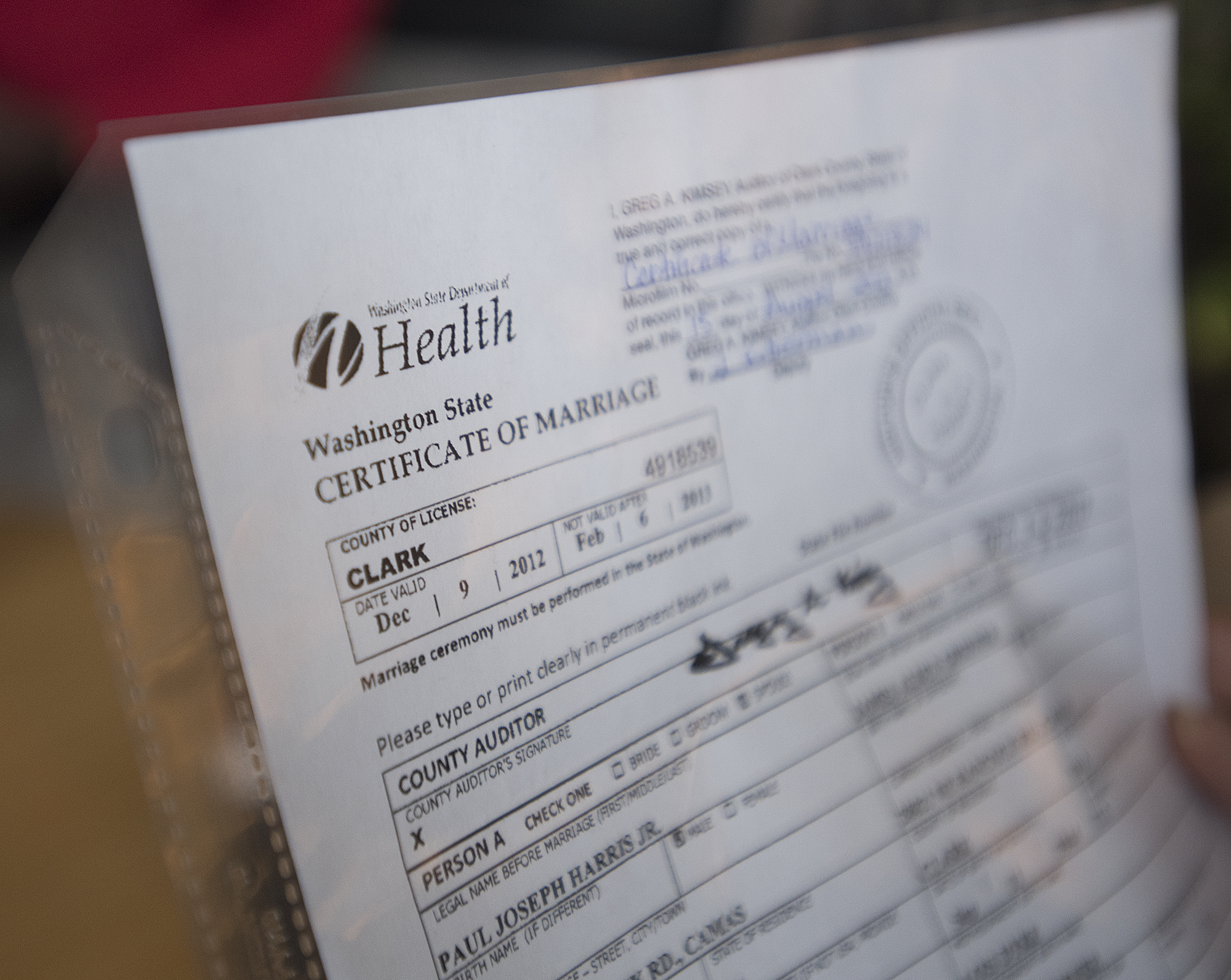

Marriage licenses

During Harris’ nearly 29 years of government work he did many jobs, including managing marriage licenses. Despite the county’s booming population, the number of marriage licenses issued annually dropped during those decades. If it weren’t for legalizing same-sex marriage, the number of new marriage licenses issued in 2013 would’ve been at its lowest point in the last two decades.

Harris chuckles thinking back on people arguing that the “sanctity of marriage” was reason enough to deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples. He witnessed some unsettling things from behind the marriage license counter. Parents signing for their pregnant underage daughters, couples who came in bickering, a young bride pushing an old groom in a wheelchair up to the counter.

Enlarge

Amanda Cowan/The Columbian

“I’ve seen women come to get marriage licenses with a black eye,” Harris said. “Even in those situations you could not deny them a marriage license. … That’s what frustrated me most because I couldn’t get a marriage license but I could see who could.”

But he couldn’t be angry all of the time. Harris and Griener marched, they demonstrated in Washington, D.C., they sang with bravado in the Portland Gay Men’s Chorus and never hid the fact that they were gay.

They also never thought that in their lifetime they could get married. Maybe the next generation. They weren’t interested in domestic partnership, though Washington boasted some of the best rights and protections.

“We looked at domestic partnership as something other, not equal. We wanted to be equal, not second-class citizens,” Harris said.

"That was an emotional day because now I’m on the other side of the counter. We sat there with tears running down our faces because of the magnitude of it.” Paul Harris

He stayed up late the night before same-sex couples could get marriage licenses, making sure that the county’s systems all worked and that the downtown Vancouver office could accommodate the rush of people. And that morning, Dec. 6, 2012, he and Griener sat down and filled out the very first application.

“That was an emotional day because now I’m on the other side of the counter,” Harris said. “We sat there with tears running down our faces because of the magnitude of it.”

Besides the traditional designation of bride and groom, the revised marriage license applications allow the option of bride and bride, groom and groom, or spouse and spouse, which is the box Harris and Griener checked. That’s how they saw each other: Spouses.

A quiet life together

“Our relationship has been very easy and normal,” Griener said. “We’ve always been out wherever we were.”

They’ve never been assaulted, they said, though there was the rare scare, such as passers-by yelling obscenities as they walked in Boston. It helps that they’ve lived in relatively accepting, safe cities for gay people. And, they said, it helps that they don’t dress or talk flamboyantly, the stereotype of what it means to be a gay man.

“James and I walking in the park, people might just think we’re friends,” Harris said.

They did just that on a quiet, gray Friday afternoon: bundling up in rain jackets and putting a harness on their black Labrador, Lucky, before taking him to Dakota Dog Park. They go there most every day.

People might not notice that the two wear identical rain jackets, just different colors, the kind of thing married people who shop together would do.

While living in Brooklyn Heights people would often walk up to the pair and — no joke — ask if they were undercover detectives. Two men walking side by side? Must be cops.

“I already have another weight to bear,” Harris said, pointing to his forearm. “I couldn’t hide the fact that I was black. I could hide the fact that I was gay. I didn’t want to do that.”

Griener had never met a black person until he went to college in Eugene, Ore. He hails from Adel, an isolated southeastern Oregon town of maybe 100 people where his mother was the postmaster and his family ran cattle and owned the general store. It’s in Lake County, where a greater percentage of people voted for Donald Trump than any other county in Oregon.

One Christmas Griener took Harris to visit his parents and they attended a dance at the local Grange hall. At one point, Griener’s grandmother took Harris by the hand and introduced him to everyone as Griener’s partner.

“It was one of the most beautiful moments of my life,” Griener said.

Perhaps it should’ve been a surprising sight: the lone black gay man being shown off to everyone inside a small-town Grange hall. Harris, though, said he’s learned something through decades of being out. “It is rare that when people get to know you they don’t treat you like a human being.”

National issues

Harris and Griener worry, though, about the separation of church and state becoming muddled, and gay marriage being undermined. The case of a Colorado bakery refusing to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple made its way to the Supreme Court last week, and the questions posed by the justices were divided. Although it’s about cakes, the ruling could apply to other wedding vendors, such as florists, photographers and tailors. It’s framed as either a case of freedom of speech and religion or discrimination.

Harris said it’s a slippery slope: “Where does that go next? You don’t want to make a cake for me cause I’m black?”

That was the argument made decades ago — that serving someone who’s black goes against religious liberty — which courts rejected.

Harris and his husband know what it’s like to have rights rescinded. They actually married once before when Multnomah County, Ore., briefly allowed same-sex marriage. It was March 3, 2004 and they stood in line in the rain with hundreds of other couples at Portland City Hall and then walked to Keller Auditorium, where mass weddings were performed.

“It was a really festive event,” Griener said, recalling people handing out doughnuts and coffee. Everyone smiling in the rain. “But very shortly thereafter they took it back.”

The licenses were invalidated and the county refunded their money.

After that, Griener began filling binders with newspaper clippings about gay marriage and rights. It pieces together the gigantic change in the attitudes of people toward same-sex relationships, he said. It’s history that’s still being written.

Though he’s slowed down since gay marriage was legalized nationwide, he has 11 binders so far and keeps adding to them.

“I have enough material to fill another 10, I’m sure,” Griener said.

Patty Hastings: 360-735-4513; twitter.com/pattyhastings; patty.hastings@columbian.com