Little evidence remains today of the fire that, 114 years ago, tore through Southwest Washington in what’s now known as the Yacolt Burn State Forest. Trees cover the landscape once again. Hikers, mountain bikers and horse riders traverse the forest. Hundreds of homes dot the area.

Until recently, the Southwest Washington blaze was the largest fire in state history, and some wonder if a fire that devastating could happen here again. Since the Yacolt Burn, much about forest management and fire prevention has changed. Officials work to balance sometimes competing interests — preventing future wildfires, preserving wildlife habitat, generating revenue and creating spaces for outdoor recreation.

These days, the risk for a large forest fire in Western Washington is lower than it used to be, but as the planet warms and droughts become more common, forest managers find that they may have to evolve yet again.

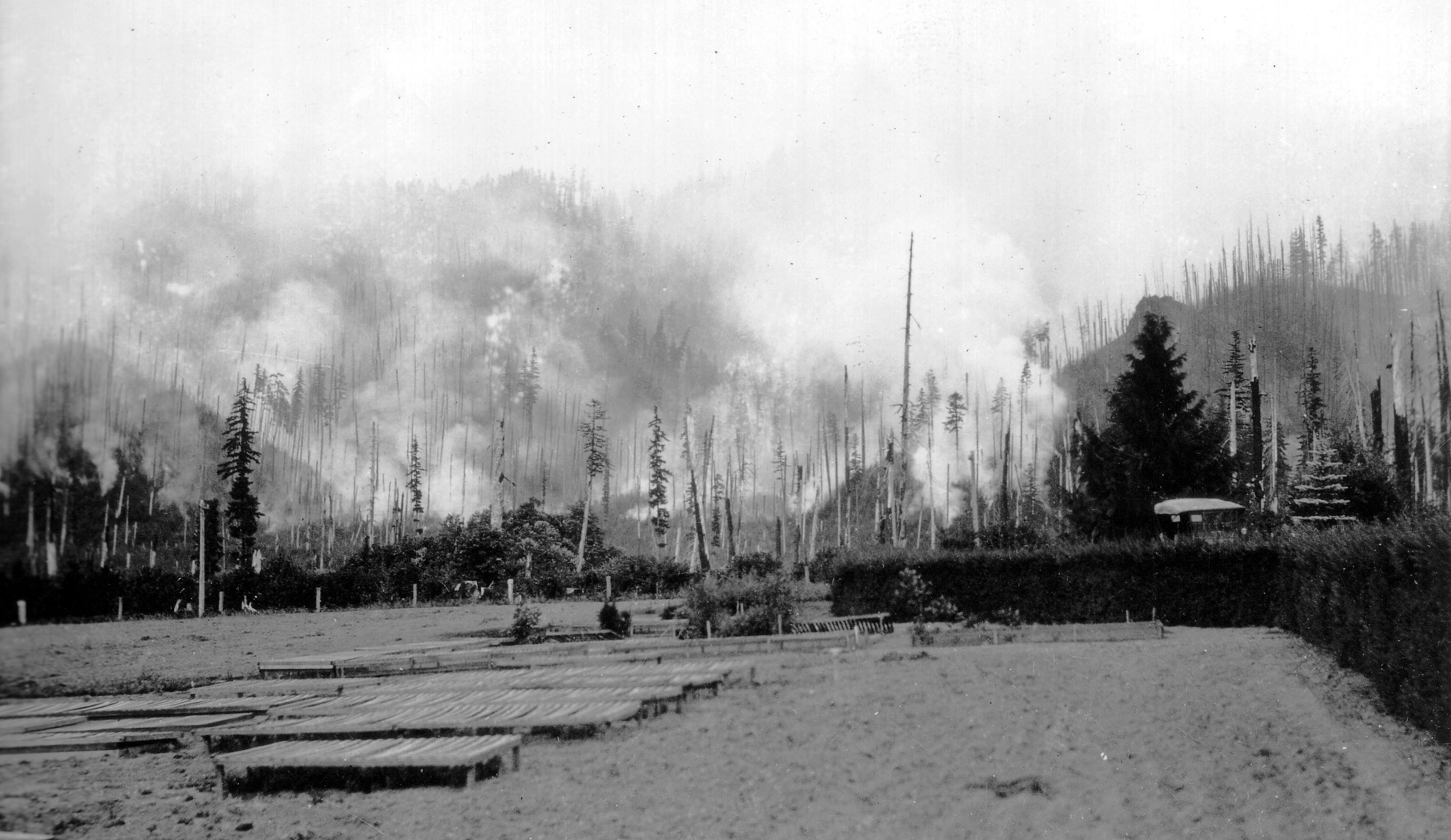

In the case of the Yacolt Burn, the September 1902 wildland fire came on the heels of 77 days without rain. In just three days, it burned more than 350 square miles — almost 239,000 acres — in Clark, Cowlitz and Skamania counties, killed 38 people and destroyed 12 billion board feet of timber valued at $30 million at the time.

“What burned in the Yacolt Burn was essentially virgin forest,” said Jessica Hudec, a forest ecologist with the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. The forest was full of vegetation with several different canopy levels — or as foresters say, it contained large amounts of biomass.

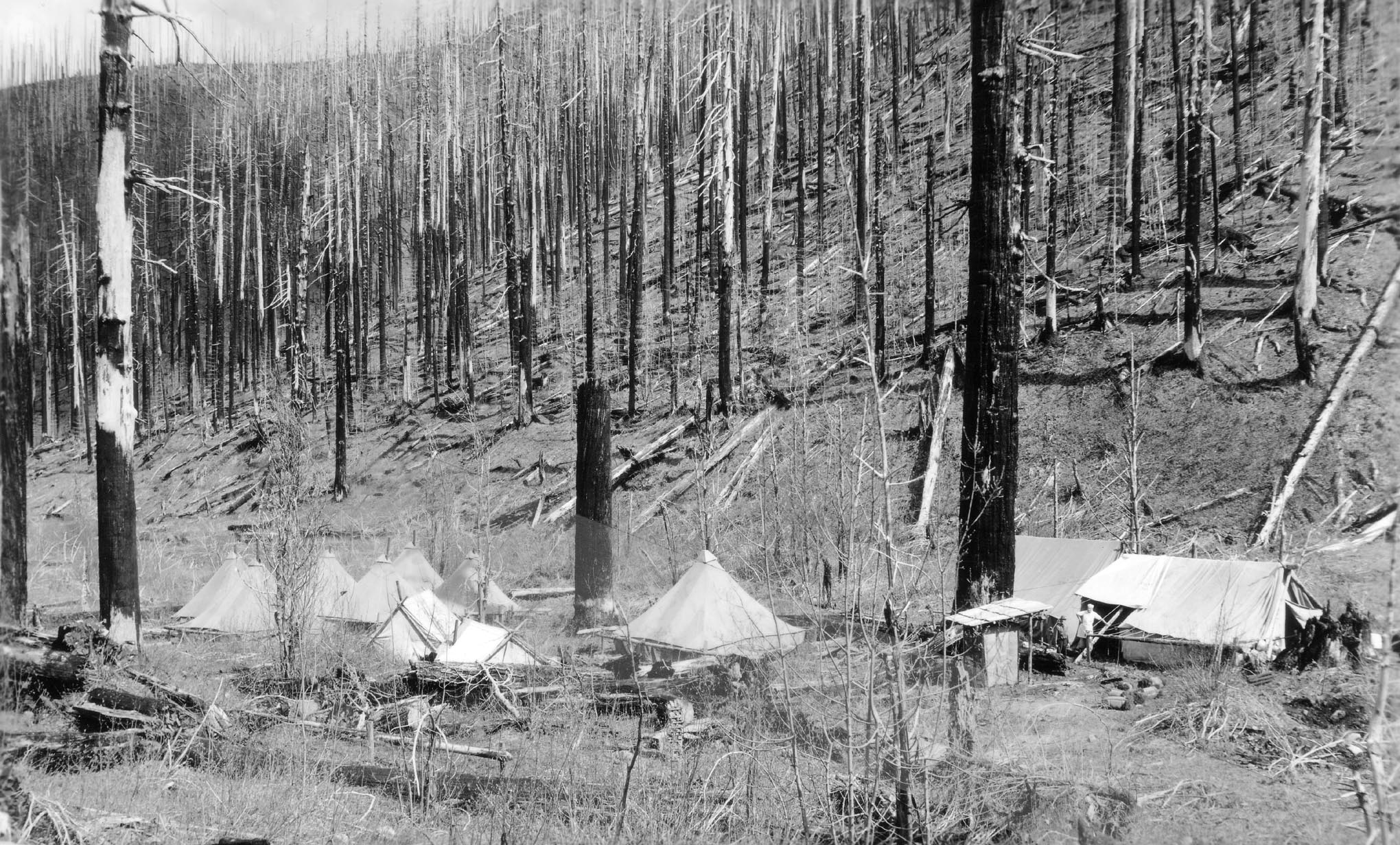

Historical photos after the blaze show a landscape devoid of plant life. Instead of impenetrable greenery, hillsides were sparsely covered with barren logs that resembled telephone poles more than trees.

Officials never found out what caused the fire, but several theories swirled, including slash burns that ran out of control, nearby trains or embers that drifted from fires in Oregon.

In 2014, the Yacolt Burn was surpassed by the Carlton Complex fire as the state’s largest recorded forest fire. A year later, the Okanogan Complex fire claimed the title.

While the 1902 burn is the most notorious of Southwest Washington’s fires, it was hardly the last. According to the U.S. Forest Service, there were 16 separate burns between 1910 and 1924 in what’s now the Yacolt Burn State Forest and the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Several more fires, burning tens of thousands of acres each, cropped up over the subsequent years just before the last big one occurred in 1952, when about 15,000 acres were destroyed by fire.

Regrowth

Rather than wait for nature to turn the charred wilderness back into a forest, federal and state land managers accelerated the process.

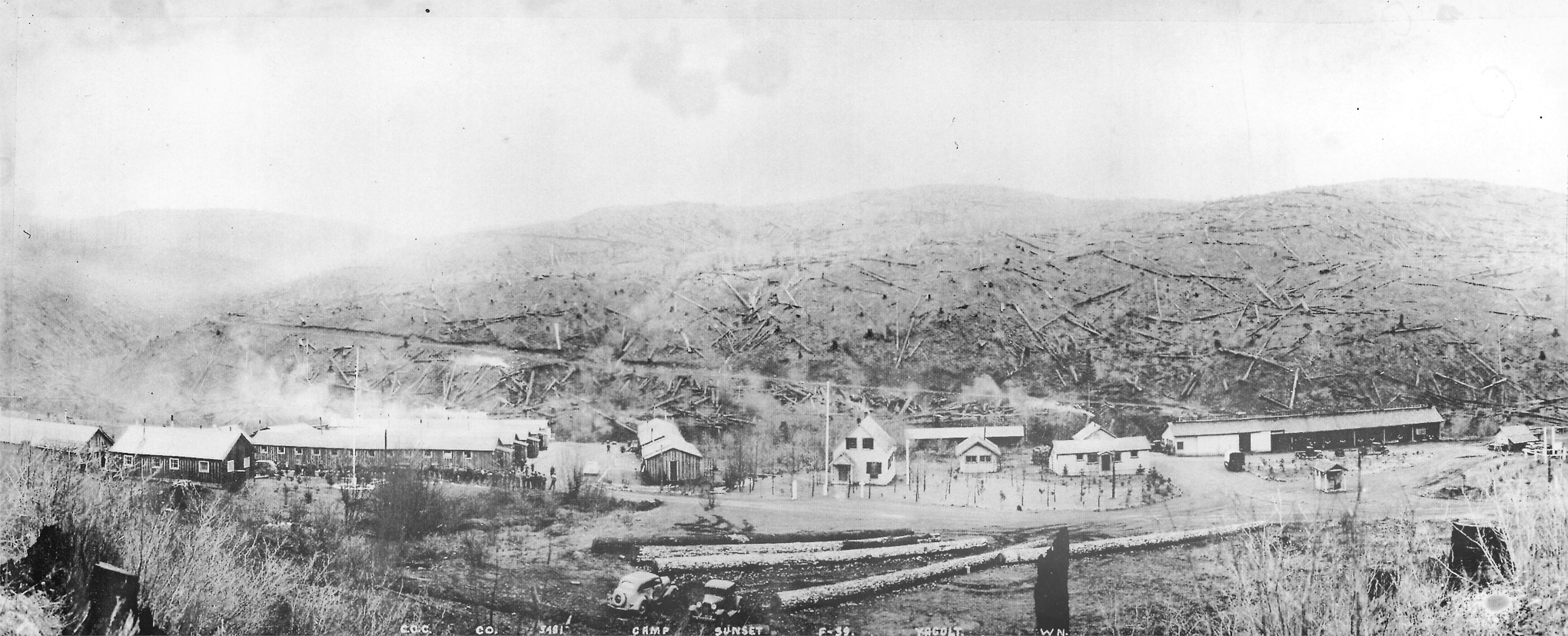

In 1910, the first federal replanting effort began, followed by work in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps. In 1955, the Washington State Division of Forestry’s Yacolt Burn Rehabilitation Project began, reforesting 110,000 acres of state and private lands over about two decades.

Not everything about the effort was beneficial, however.

“There was definitely a foot to the gas pedal after the 1902 fire,” Hudec said of the forest-replanting process. “We took what was essentially an old-growth Western hemlock forest and converted them into Douglas fir plantations in order to grow trees.”

Because of mixed results with forest seeding, crews planted saplings by hand. On some steep areas, crews terraced the hillsides. However, Brian Poehlein, the state Department of Natural Resources’ lands manager of the Yacolt District, said the terraced areas he’s seen didn’t have strong regeneration.

“The concept was good, especially for erosion purposes, but then you gotta think about, what did it do to the soil fertility?” Poehlein said.

In light of the nearly 20 fires that burned after the big blaze, foresters focused on removing the standing dead trees left behind by the fires, called snags, for fear that they would serve as kindling for the next one.

According to the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, snags can provide more habitat for wildlife than living trees. Animals use them for food storage, foraging for insect dens and nurseries. When snags do fall they benefit ground-dwelling animals and can contribute to stream health.

“At this point we don’t remove snags because of fire hazards. They’re way more valuable as wildlife habitat,” said Steve Ogden, assistant regional manager of DNR’s Pacific Cascade Region. “The landscape is pretty devoid of them because so many of them were removed. So in certain places we’ll create them for habitat.”

Today the 63,000-acre Yacolt Burn State Forest is trust land managed by the DNR as a working forest. Around Larch Mountain in northeast Clark County, the forest is a patchwork of timber stands ranging from tiny saplings to decades-old trees waiting to be felled, the funds from which will go to state trust beneficiaries.

Some of the oldest post-fire trees are in riparian areas along streams, protected under state law to preserve water quality. There also are several day-use recreation spots and campgrounds in the area with miles of trails.

Then vs. now

Fire frequency in Southwest Washington has slowed dramatically since the 1950s. In recent decades, the region’s population growth has accelerated, and many residents are building homes in rural, forested areas outside of cities. The DNR estimates 2 million people now live within a 45-minute drive of the Yacolt Burn.

Fire is still a natural part of the ecosystem, but forestry officials say it’s unlikely, but not impossible, a fire of the same magnitude will return any time soon. Before the 1902 burn, the old-growth forest was suffering from a prolonged drought. Once the fire started, it was exacerbated by very strong winds.

“I’m not going to say it can or can’t happen again because we don’t know, but the big difference between then and now is the type of fuels out there,” Ogden said.

The reforested Yacolt Burn State Forest has less biomass to burn than the pre-fire, old-growth forest.

“This area was just being developed. It was largely untouched, unmanaged kinds of stands,” Ogden said. “Today, we have younger plantations. Those were older forests that were out there.”

Hudec said that forests on the west side of the state don’t burn on a massive scale very often. Forests here typically operate on a large-scale fire interval between 100 and 500 years.

But the effects of climate change, such as high temperatures and prolonged periods of droughts, add to the possibility of more fires, so officials take steps to prevent fires from igniting and to keep them manageable when they do start.

Forest ecologist Hudec said the Forest Service has a full-time fire prevention technician stationed in Amboy who also teaches wildfire prevention to the public. She also helps local government agencies create and update community wildfire protection plans and secure federal funding when needed.

DNR recently added more staff to respond to fires. They also educate the public on fire prevention techniques and how to comply with burn bans. During fire season, the agency has fire crews on hand seven days a week.

According to Ogden, DNR employs inmate crews from Larch Corrections Center and hires contractors to reduce forest fire fuels around neighboring communities to protect them from possible wildfires.

“The potential is there,” Hudec said. “If there’s an ignition and an east wind event … and if this fire gets going, it’s going to be pretty hard to stop.”

Dameon Pesanti: 360-735-4541; dameon.pesanti@columbian.com; twitter.com/dameonoemad