Scott Skeans inched his sky blue 1961 Ford Falcon forward on Interstate 205 on the rainy afternoon of Dec. 15, 1982.

He was joined by more than 100 other vehicles, some with balloons tied to them. Members of a motorcycle club idled nearby wearing star-spangled red, white and blue armbands.

Skeans rolled his Falcon forward three feet — and collided with the rear bumper of a pickup truck. There was no damage, and the truck driver didn’t care.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

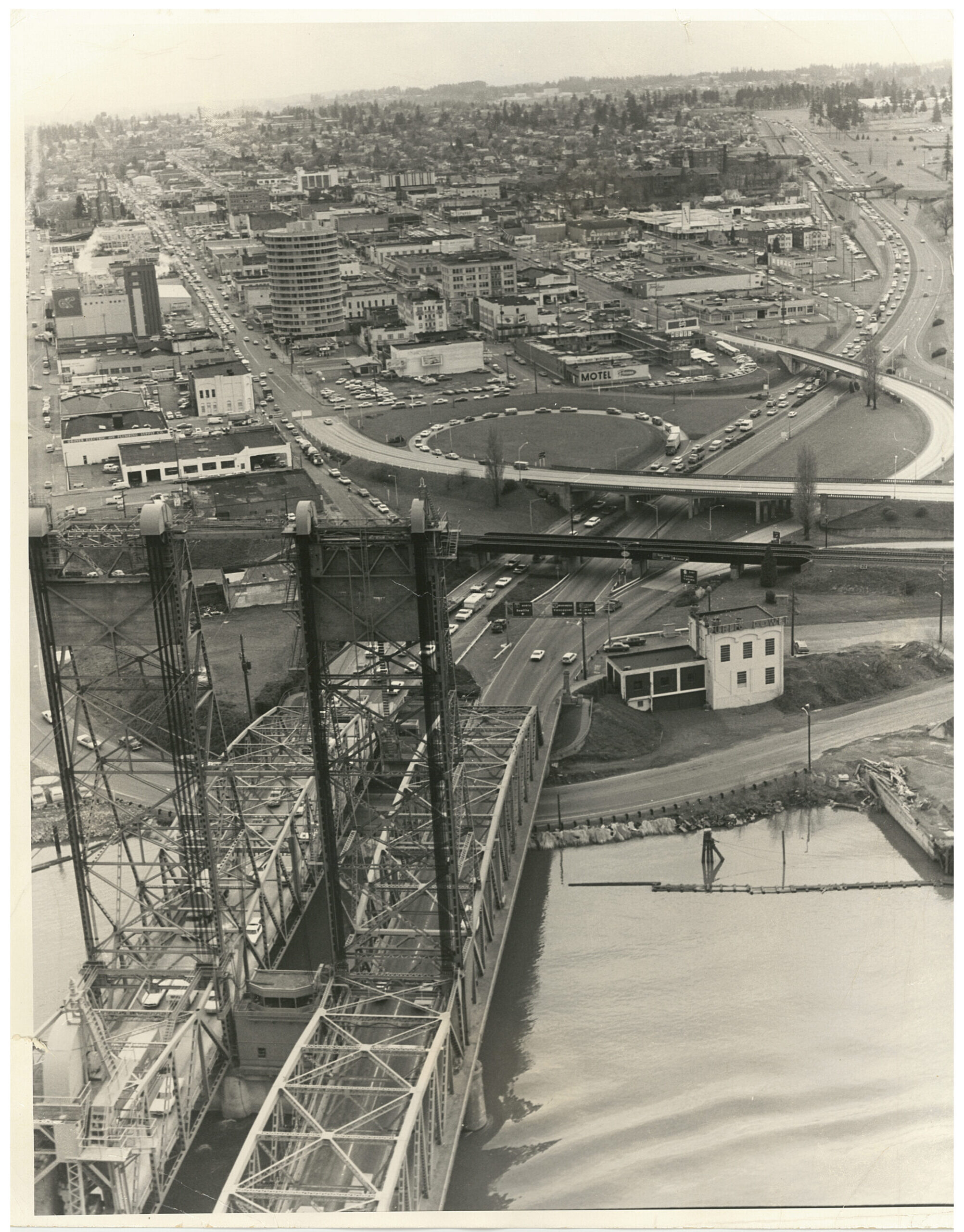

Both were focused on the ceremony ahead, where the governors of Oregon and Washington along with politicians, bureaucrats and engineers huddled under umbrellas. The governors were tying a ribbon together — a symbolic gesture of the two states linking hands across the river — and celebrating the opening of the Interstate 205 Bridge.

There was no backslapping or long speeches — those were saved for a luncheon at the Jantzen Beach Thunderbird afterward — and they hurried off the bridge to allow traffic to rush over the new crossing.

The new bridge cost $175 million and faced huge delays and arguments over its details. There were lawsuits, and three workers died during construction.

It was hoped that all of Clark County would benefit from the Interstate 205 Bridge, as Vancouver did from the Interstate Bridge. The 1917 span made Vancouver a sort of suburb of Portland; no longer did travelers between the two states have to commute by ferry. But with the I-205 Bridge, it was hoped that all of Clark County could become a suburb of Multnomah County.

In the end, most of the leaders involved with I-205 cycled through before the bridge opened. Even Glenn Jackson, the bridge’s namesake with the reputation as the most powerful man in Oregon, died in 1980, two years before the bridge opened.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Crossing the Columbia: East vs. West

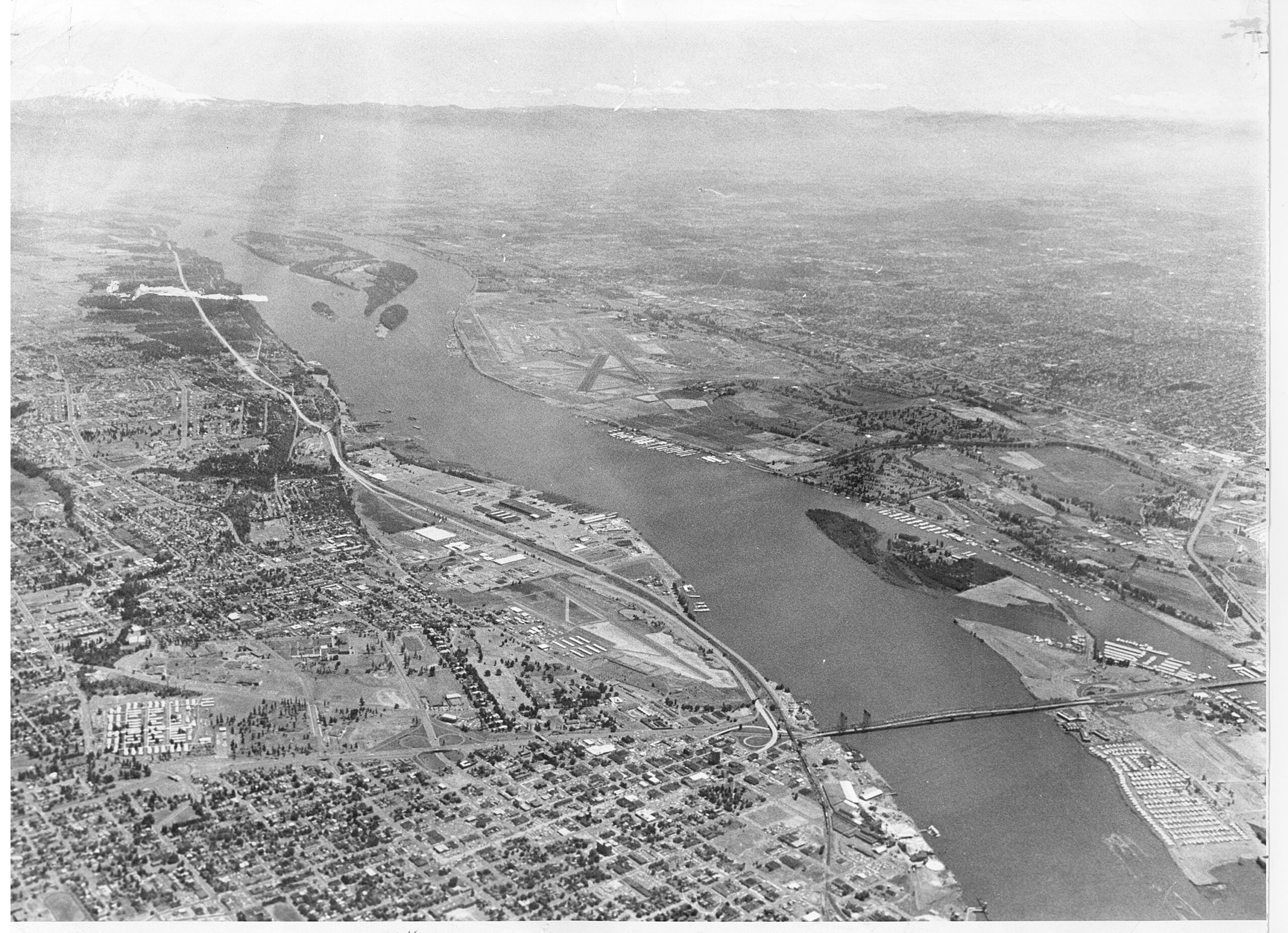

Even before the second span of the Interstate 5 Bridge was built in 1958, there was a desire for another river crossing to the east.

In fact, the region nearly got two eastern crossings.

In 1943, Robert Moses, a New York urban planner and the former secretary of state of New York, published the “Portland Improvement Plan,” which called for a new interstate bridge and two new highway throughways in Vancouver. Moses’ plan would have connected a new bridge to East Reserve Street near Pearson Field.

Many Clark County residents wanted a second bridge to be built even farther east. Spots on either side of Portland International Airport were eyed: one at Blandford Drive, in what is now central Vancouver, and in Fishers, in what is now east Vancouver.

But there was a hitch: Both potential new bridges were within 10 miles of the Interstate 5 Bridge, and a state statute prevented construction of any new river crossing within 10 miles of an existing toll bridge as long as the bonds were outstanding, said state Attorney General John O’Connell.

The workaround: move the easternmost bridge 1½ miles east of Fishers so it would be 10.1 miles away from the Interstate 5 Bridge.

The proposed Fishers bridge would cost $6 million for a three-lane span or $5 million for a two-lane span. It would be tolled until 1976, when the toll-free freeway bridge at Blandford Drive in Vancouver was slated to be opened.

Because the Fishers bridge was to be funded via tolls, its viability depended on when the Blandford Drive toll-free bridge would be erected; too soon, and hardly anyone would drive over the toll bridge.

In 1962, the idea of a toll bridge at Fishers died as it was deemed financially unfeasible. Construction of I-205 and its own interstate bridge would trim toll revenue drastically before the Fishers-area bridge could be paid off.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

A new path

In September 1962, the Oregon Highway Department studied putting the I-205 Bridge in the Ellsworth area — the area where it was ultimately built — instead of at Blandford Drive. Completion was expected by 1972.

Some Vancouver leaders had worried that the Blandford Drive location would provide Vancouver residents with a toll-free straight shot to tax-free shopping at the Lloyd Center. Many city and county officials were less concerned about which location was picked, but they wanted a study to be completed before a site was selected.

The study was released in May 1964, and it confirmed that both locations were viable. The decision would ultimately be made by the Oregon Highway Commission, because Oregon had a higher population and was covering more of the cost, although the vast majority was being funded by the federal government.

Clark County leaders lobbied for the Blandford Drive site, arguing it would better relieve traffic congestion on the I-5 Bridge, although they conceded an east route would ultimately be necessary.

“From Clark County’s standpoint, both the ‘east’ and ‘west’ bridges will undoubtedly be needed, but if the battle now brewing becomes too intense, we could likely end up with neither under the present Interstate 90-percent financing legislation,” The Columbian editorial board wrote in July 1964.

“Let’s hope that the upcoming ‘east-west’ fight won’t result in suicide by strangulation,” they added.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Looking east

In October, the Oregon Highway Commission accepted the highway engineer’s recommendation for the eastern I-205 route. The freeway was projected to cost $90 million, and construction was targeted to start in July 1965.

The decision drew the ire of some local leaders and the Coordinating Committee of the Portland-Vancouver Metropolitan Transportation Study, but there was little that could be done.

Nearly everyone wanted the bridge, especially with much of the bill being footed by the feds, and Clark County leaders believed it would result in a boon for the region, accelerating “the value of Clark County’s expansive areas as a bedroom for the Portland metropolitan complex,” one economic forecast said.

By year’s end, the Oregon Highway Commission adopted the plans for I-205. It would depart from I-5 at Avery Road in Washington County, pass through West Linn, cross the Willamette River near Oregon City and follow 96th Avenue through Portland and swing across the Columbia River and land in the Ellsworth area of Clark County.

Tired of the drawn-out effort, Oregon Highway Commission Chairman Glenn Jackson was ready to move on.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

“This thing has been pending for many months and has created unsettled conditions for people along every route we have proposed. It’s caused turmoil, and now it is up to us to act,” he said. “We can’t just go on like this.”

The plan was finalized in March 1966 when the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads gave its seal of approval.

Stop and go

With the crossing site picked, highway officials could start planning the road and bridge in greater detail. Given the bridge’s proximity to Portland International Airport, constructing the bridge would be a tight fit.

The Port of Portland was worried about how the airport would serve a projected 7 million passengers in 1980. In preparation, it was considering a new 1,200-foot runway to the east.

As a result, Oregon officials considered changing the layout of the I-205 freeway. It was not expected to impact the freeway in Clark County, although the bridge and approaches would need a “little more angle,” The Columbian reported.

The biggest fear was delays.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

By June 1968, it was clear that the airport’s proposed expansion might not be the only hurdle for the I-205 Bridge. Issues between the Federal Aviation Administration and the Coast Guard over the bridge’s proposed height might be, too.

The Coast Guard worried the bridge would not provide enough vertical clearance for ships, and the FAA was concerned that the bridge might be too high and impinge on the glide path of planes; the bridge would technically violate FAA regulations by being as much as 38 feet higher than the desired standards, according to one airport official.

A partnership

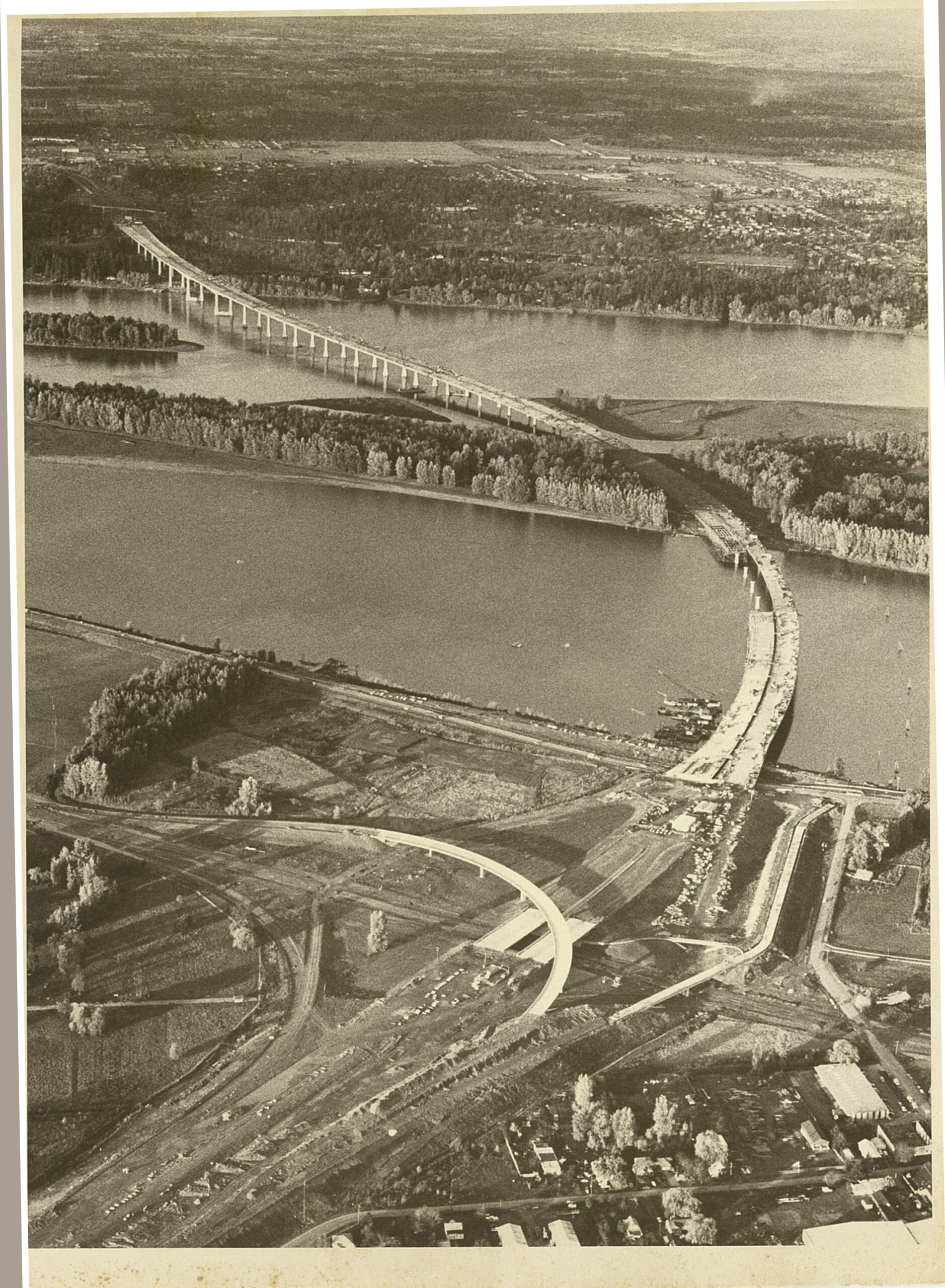

By May 1969, the FAA announced that the I-205 Bridge would not pose a hazard to the present or future use of Portland International Airport. Due to the proximity between the proposed I-205 and airport expansion, the two entities decided to work together.

To expand the airport, Port of Portland officials planned to dredge sand in the Columbia River near Government Island, and part of the dredged material was to be used for fill at the bridge site.

But the plan was put in jeopardy when the port and other federal officials and agencies were sued by the Council for the Citizens Committee for the Columbia River and the Sierra Club. The groups claimed that approval for the project was given before proper consideration by the necessary officials and agencies.

The lawsuit caused the start of construction on the I-205 Bridge to be delayed indefinitely.

In the meantime, local and Washington officials were continuing to plan and procure the right of way for the rest of I-205 through Clark County, but it would only be so useful without the bridge.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

More delays

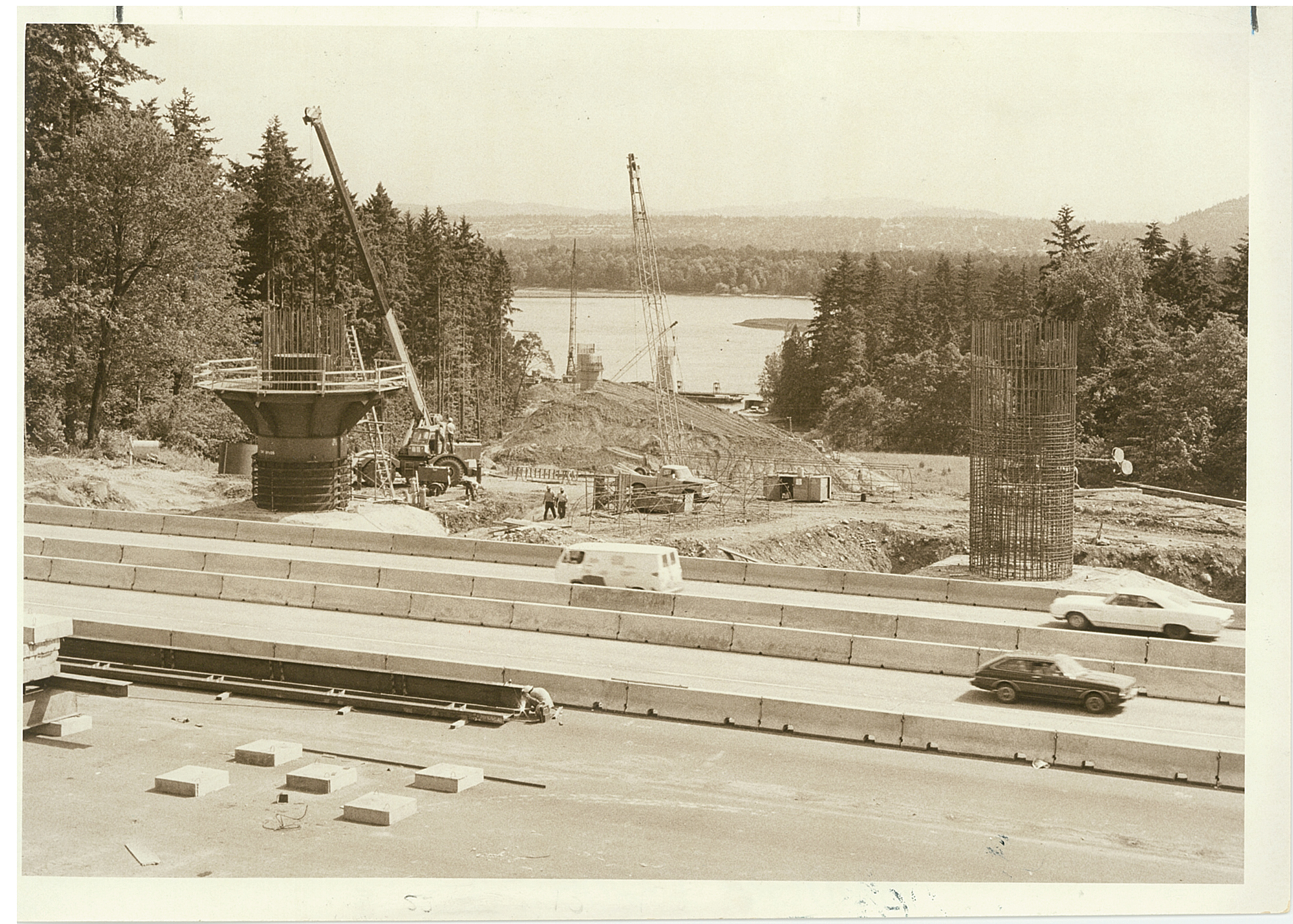

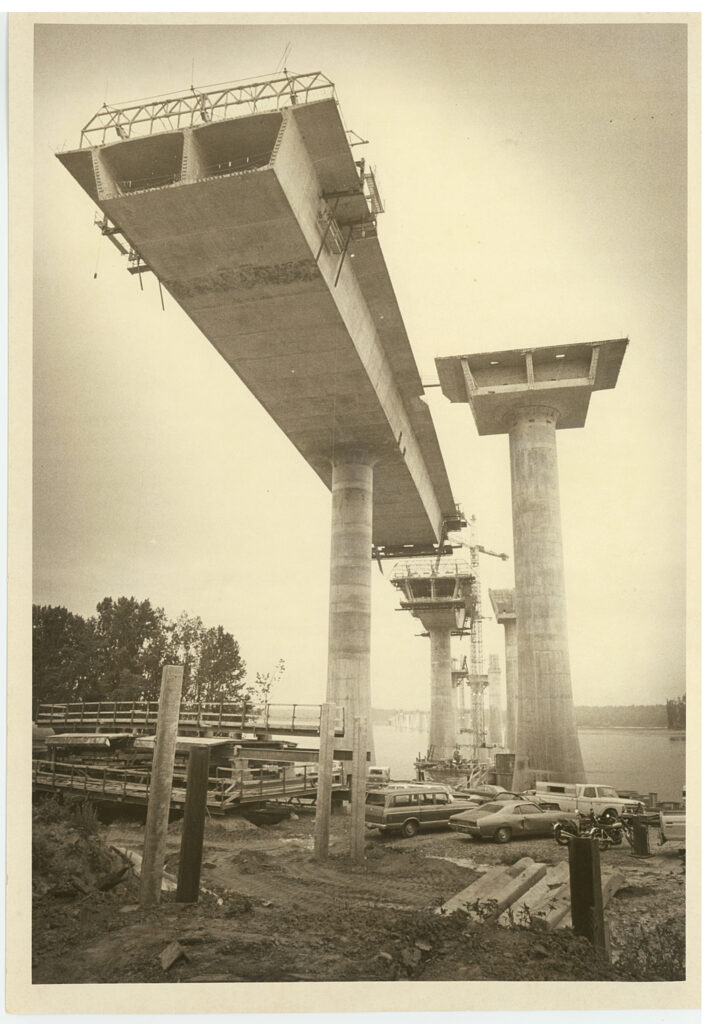

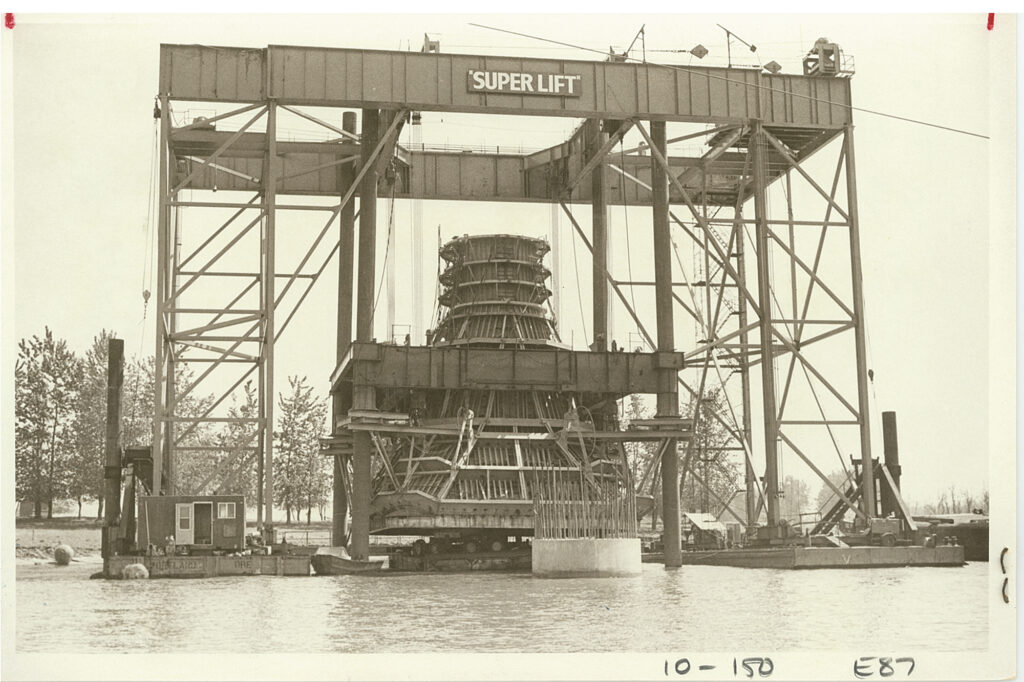

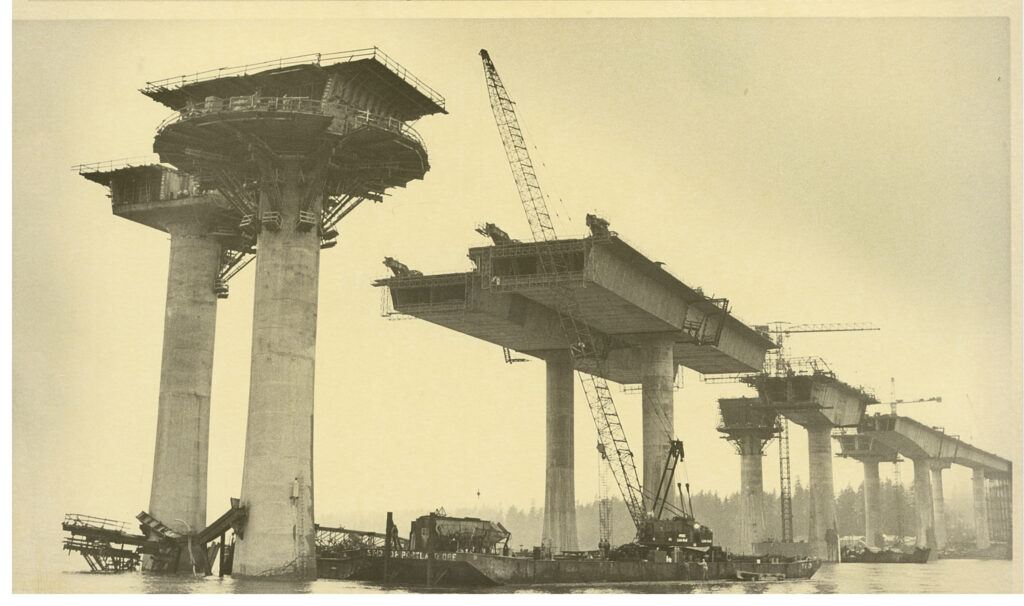

One of the final milestones before construction could begin came in September 1971, when the Federal Highway Administration approved the bridge’s preliminary design. It was to be long and slim, due to limitations from the FAA and the Coast Guard, and it had an estimated cost of $68 million. The final design was targeted for early 1973.

The approved design had one glaring omission: There was no bicycle-pedestrian path. The Federal Highway Administration said its $3.8 million price tag was too much; politicians, including Washington Gov. Dan Evans, urged highway officials to reconsider.

The airport lawsuit was still grinding on in the background, and the projected opening of the bridge was pushed back until 1977 or 1978. During the delay, construction costs were rising at an estimated 7 percent to 8 percent annually, The Columbian noted.

Partnership ends

By the end of 1972, officials on both sides of the river, including Portland Mayor-elect Neil Goldschmidt, suggested the bridge and airport expansion should be done separately. The cost, an extra $20 million to $25 million, proved to be the largest barrier in separating the two.

U.S. Rep. Mike McCormack, D-Wash., asked the Oregon Highway Department to conduct an environmental impact statement of the bridge separately from the airport expansion. He wanted to examine the positives and negatives that would result from decoupling the projects, but the highway department declined.

By 1973, nearly all of the I-205 freeway was built except for the bridge and a stretch in east Portland deemed “the missing link.” Tensions around the lack of activity on the bridge rose throughout the first half of the year, leading to Washington Highways Director George Andrews to decry that Oregon’s “principal concern has been for the airport. … They really could have cared less about the Interstate (205) Bridge.”

In July, the Port of Portland announced that it would drop its efforts to expand the airport by putting fill in the Columbia River, which essentially decoupled the two projects.

“Except for some Oregon Highway officials, cancellation of expansion plans for (the airport) generally has been hailed in the area as removing a roadblock to the proposed I-205 Bridge,” The Columbian editorial board wrote.

Even more delays

Eventually, an eight-foot bike path was added to the bridge plans, which — combined with the abandonment of the Port of Portland’s plan to expand the airport onto fill in the river — delayed construction another two years.

In July 1974, the Multnomah County commissioners voted to request a redesign of the I-205 freeway to reduce its impact on east Portland. The motion withdrew the county’s support for the highway and declared it “not in the public interest.” A new design proposal was not specified, but Commissioner Mel Gordon called for reducing the route to four lanes rather than eight. ODOT officials estimated a redesign would probably set the project back 18 months.

One Washington highway engineer said in September 1974 that although work on I-205 in Washington was continuing without any issues, they’d “be reluctant to begin any bridge work before we find out what’s going to happen across the river.”

In March 1975, Multnomah County commissioners approved construction of I-205 through Portland, but they stuck to their earlier contention that a nine-mile stretch in east Portland should be redesigned.

Construction starts

“We were afraid we’d never live to see” construction begin, admitted Jackson. He was 75 years old when construction started in August 1977. Construction was scheduled to take five years.

During the groundbreaking ceremony, Oregon Gov. Bob Straub made a surprise announcement that the bridge would be named after Jackson, the chairman of the executive board of Pacific Power and Light Co., chairman of the Oregon Transportation Commission and co-publisher of the Democrat-Herald in Albany, Ore.

Jackson’s name seemingly held as much weight to Vancouverites in 1977 as it does today. The Columbian ran an article about the Oregon power player titled “Glenn Who?”

The idea for the bridge’s name stemmed from Eric Allen, the editor of the Medford Mail Tribune. Because most of the bridge is inside Oregon, and because Oregon was footing the bill for 85 percent of the local share of the cost, Straub believed he had the right to do it. Officials in Oregon said they talked with Washington’s highway director about the name idea.

Disaster

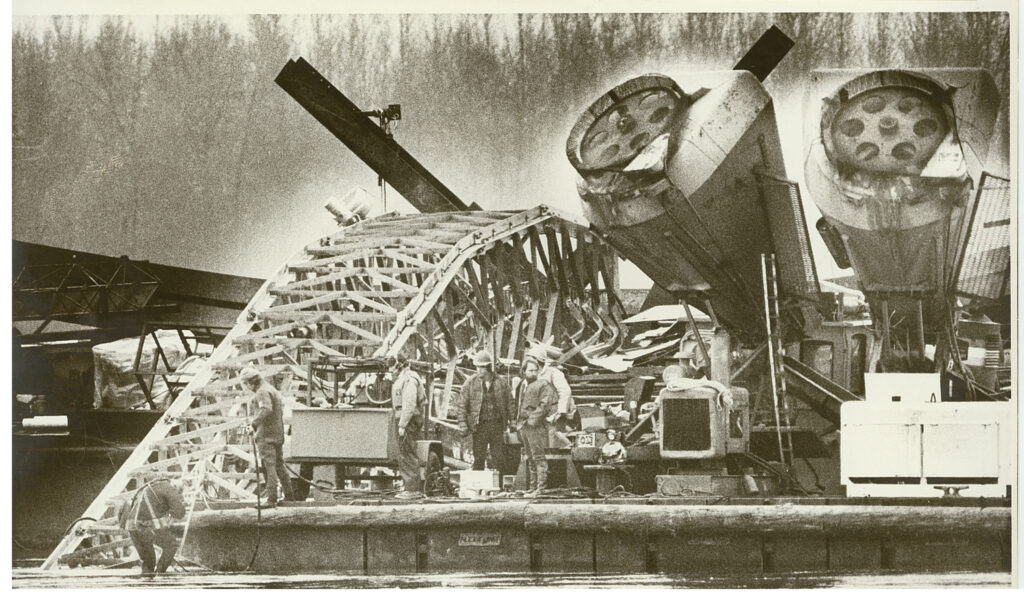

On Dec. 3, 1980, tragedy struck.

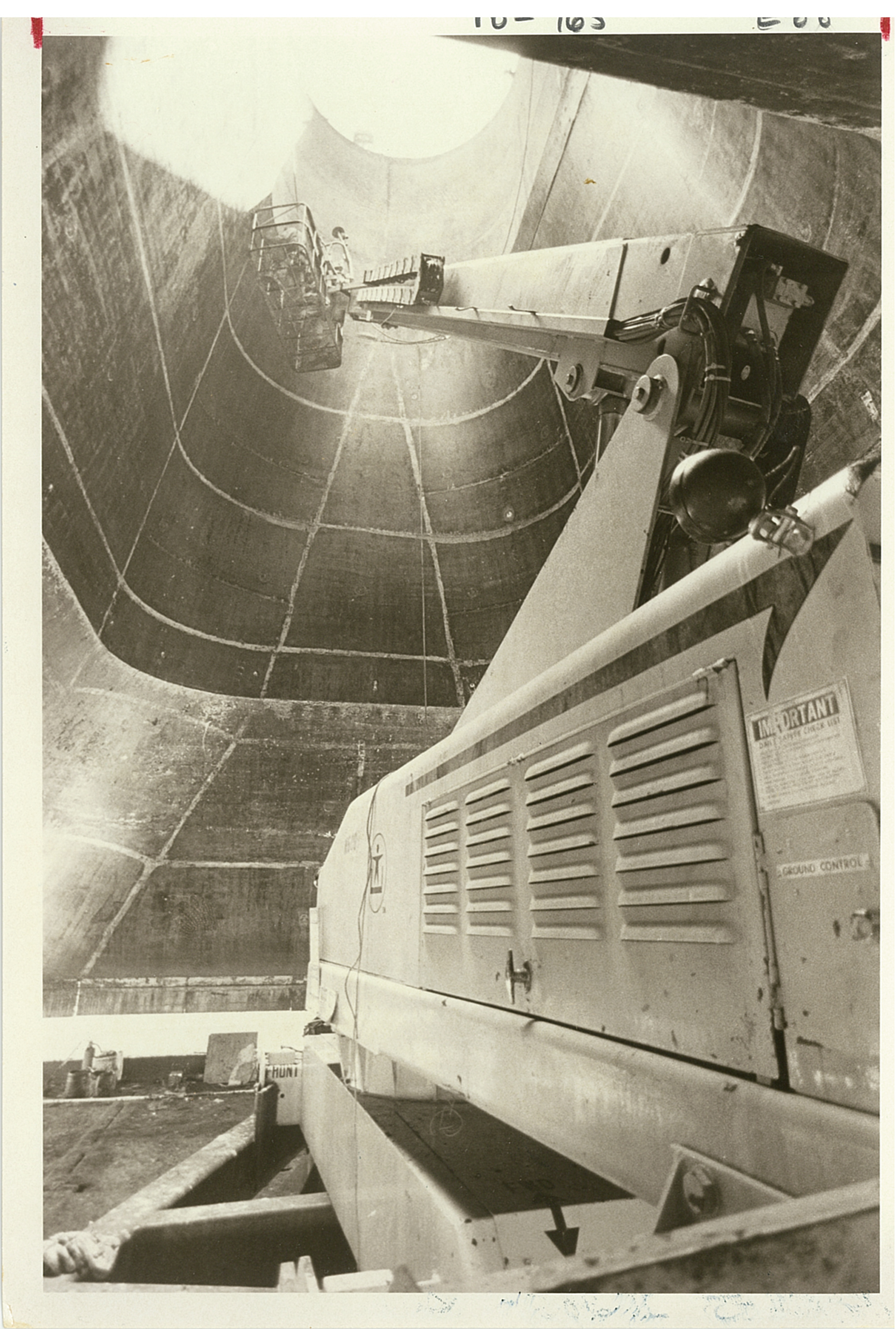

On a dark and windy evening with gusts averaging 17 mph and as strong as 26 mph a construction worker heard a boomlike sound and turned to see a giant splash in the Columbia: one of the construction cranes had snapped. The crash killed two: the crane’s operator who was found trapped in the operator cabin under 30 feet of water, and a worker who was riding a steel-framed “cage” like an elevator as the crane was hoisting it up 137 feet above the water.

The crane crash wasn’t the first fatal accident in the bridge’s construction. A foreman died in March 1979 when he fell approximately 70 feet from a scaffolding while doing concrete work on the bridge. He was rushed to the hospital where he died of internal injuries.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Bridge opening

Years later, Skeans, the man involved in the bridge’s first fender-bender, looked on at the 200 people huddled under umbrellas for the “ribbon-tying” ceremony. The gesture was intended to symbolize that the bridge was not just concrete, but a gateway between the two states. Washington’s ribbon was green and white and Oregon’s was blue and gold.

“I have not seen enough ribbons tied like this,” remarked Washington Gov. John Spellman. “I would like to see more.”

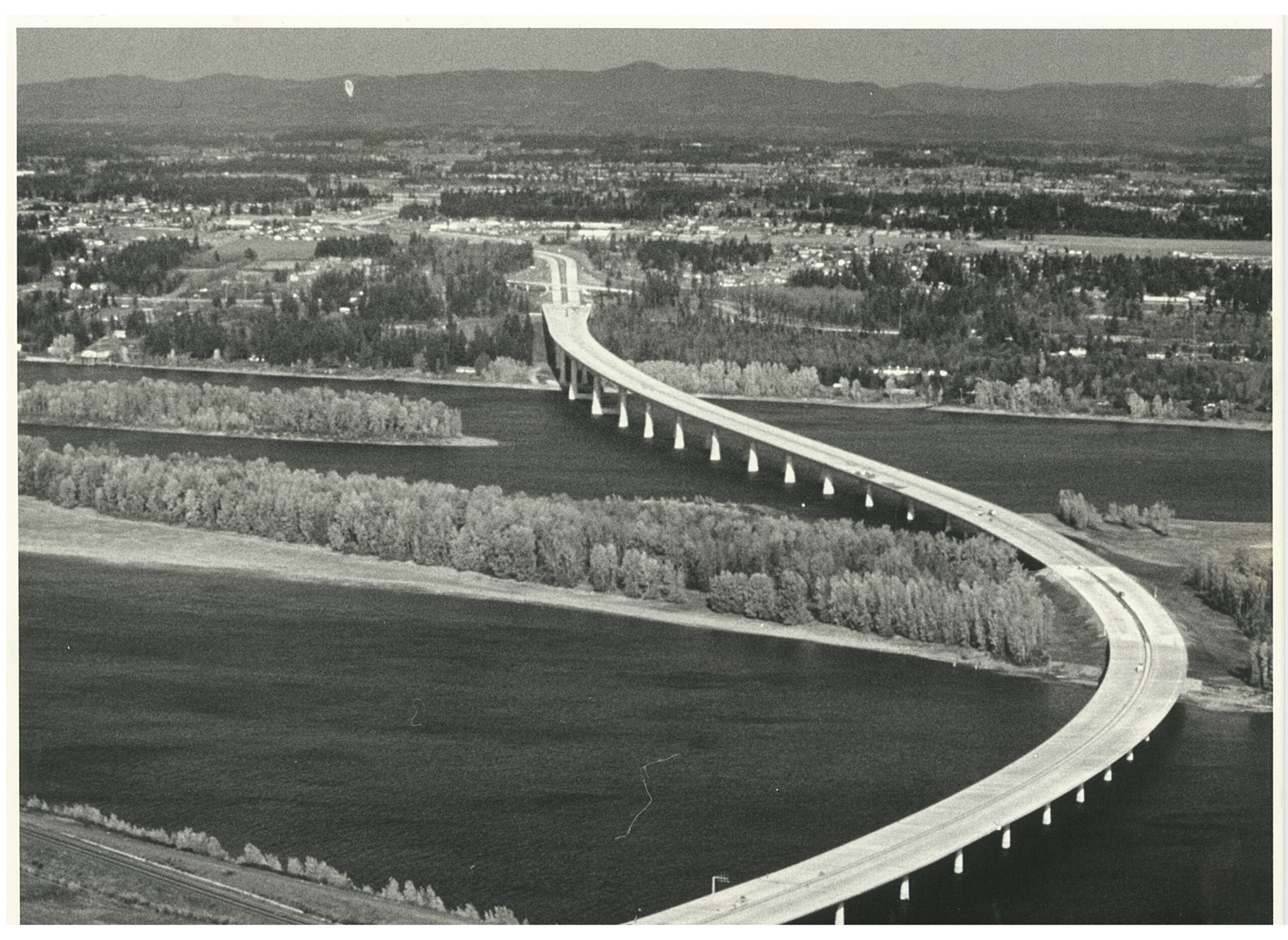

By the time the bridge opened in December 1982, it was estimated that 27,000 vehicles would cross it every day in 1983 and that by 2000, that number would rise to 63,000.

The estimates were off. In the first year, the bridge averaged 38,412 weekday crossings. In 2000 there were 132,159 average weekday crossings.

Although the freeway was expected to relieve Interstate 5 when it was being planned, by the time it opened, the thinking had changed.

“The experts now think I-205 will, in effect, create the traffic it carries rather than taking much load from I-5,” The Columbian wrote.

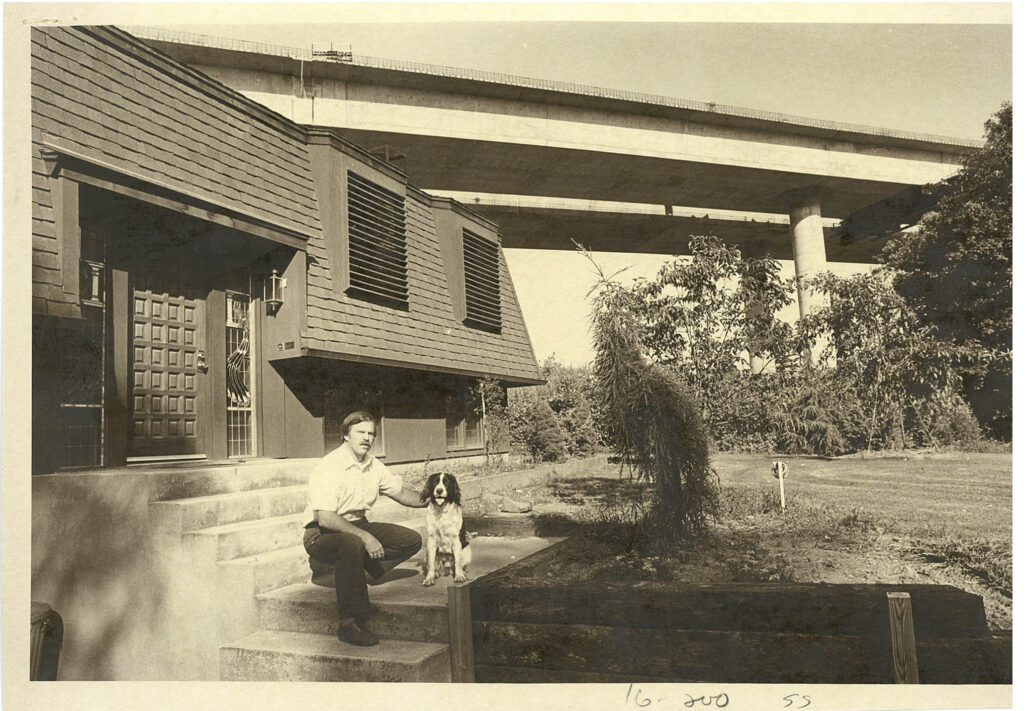

Although speculation of the benefits and consequences of the new bridge’s ripple effects were ripe, the bridge’s shadow wouldn’t fully be seen until decades after.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Over the next 20 years, Clark County’s population nearly doubled, much of it centered in the east. By 1997, the I-205 Bridge experienced more average weekday trips than the Interstate 5 Bridge. And in 2019, the I-205 Bridge averaged 160,000 weekday crossings compared with the I-5 Bridge’s 138,000.

“Almost everyone has a guess about what the bridge will mean,” The Columbian wrote. “Nobody really knows. The changes could be at least as profound as those worked by the opening of the Interstate 5 Bridge, and nobody came very close to predicting what that would do to sleepy, isolated Vancouver.”

About the project: Community Funded Journalism is a project from The Columbian and the Local Media Foundation that is funded by community member donations, including Connie and Lee Kearney and Steve and Jan Oliva. The Columbian maintains editorial control over all content. For more information, visit columbian.com/cfj.