How many trees call the city of Vancouver home? And what kinds of trees are they? Not even Charles Ray, Vancouver’s urban forester, knows all the answers.

The current estimate of individual trees in Vancouver’s public spaces — parks, streetscapes and medians — is a leaf or two under 100,000, according to an August 2023 update of Vancouver’s Urban Forestry Management Plan. Multiple inventories conducted by professional arborists and AmeriCorps volunteers have identified at least 345 unique tree species in those public places.

Trees growing on private property have never been inventoried. That gargantuan task would surely add many hundreds of thousands to Vancouver’s true tree tally.

Given such dizzying numbers and varieties, positive tree identification can be a tricky task, even for experts.

“You might see a silhouette from down the block,” Ray said. “As you get closer you start pulling more information in, you take in everything you can about the tree, and you start rolling through the Rolodex in your brain. It takes a while to get really good at it.”

Don’t have a tree Rolodex upstairs just yet? You could try turning to a handy cellphone app like Pl@ntNet, which compares the photo you take of your mystery tree (or any other foliage) to a vast database that’s always growing as it’s fed by millions of your plant-curious peers. But maybe that exhaustive data is too much of a good thing, because Pl@ntNet tends to respond with a menu of likely matches, leaving it to you to make the final determination. That’s why Ray isn’t a fan, he said. (Another leading, free plant ID app is iNaturalist, which isn’t quite as simple to use.)

Name that tree! Here’s help:

NorthWest Plants Database system: pnwplants.wsu.edu

Common Trees of the Pacific Northwest: treespnw.forestry.oregonstate.edu

Native Plants PNW: nativeplantspnw.com

The Tree Guide: www.arborday.org/trees/treeguide/

“I suggest that folks start small, learning to recognize a few key plants and then slowly building over time,” said Erika Johnson, coordinator of the master gardener program at Washington State University Clark County Extension.

Johnson likes flashcards for learning trees. The top name in tree ID cards is Sibley, which published a coast-to-coast “Sibley Tree Identification Flashcards: 100 Trees of North America,” but you can get closer to our local region with cards and fold-out guides like “Sibley’s Common Trees of the Pacific Northwest” and “Pacific Coast Tree Finder” and books like “Tree to Know in Oregon and Washington.”

Life in fast-paced, urbanized America tends to fill our heads with the artificial world, not the natural one. (Bet you can recognize more media stars, cars or even candy bars than types of trees!) There’s even a scientific term, discussed by biologists and botanists since the late 1990s, for the way people discount, ignore or don’t even notice greenery: plant blindness.

Does that sound like you? Don’t feel too bad. Plant blindness seems to stem both from our unfortunate, widespread alienation from nature, as well as from the human eye’s natural alertness to movement and potential threat. Your eyes tend to filter out background greenery unless you make a point of filtering it back in.

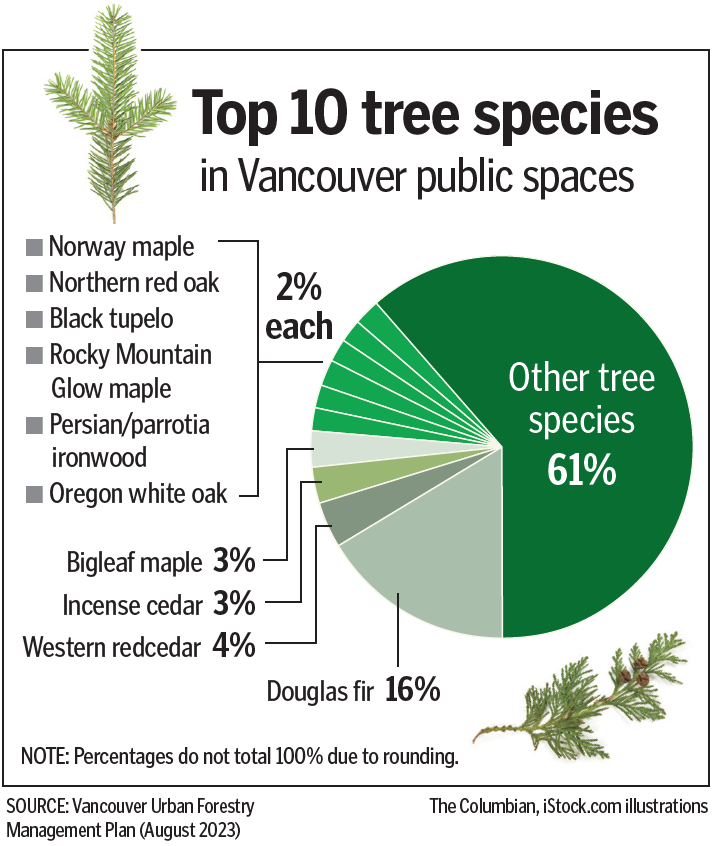

Following is Vancouver Urban Forestry’s list of the 10 most common trees you’ll see in public spaces, and how to know which is which. Because the city’s top-10 list only accounts for 39 percent of the total tree species in Vancouver’s public spaces, we added a few more prominent tree types you’ll likely see in Southwest Washington. (A generally accepted diversity goal is for no tree species to account for more than 10 percent of the local population, according to the city’s urban forestry plan. At 16 percent, Doug fir is the only tree in Vancouver that exceeds this goal. The other nine species are all in the low single digits. “Other” accounts for 61 percent.)

Information was drawn from lists and databases maintained by numerous sources, including Washington State University Clark County Extension, Oregon State University College of Forestry, Native Plants Northwest, Northwest Conifers and the Arbor Day Foundation.

Douglas fir

Your archetypical made-for-TV Christmas tree is this signature Pacific Northwest evergreen. Elegant, soft-to-touch, inch-long needles encircle its branches. Cones are scaly, with what look like long hairs (or mouse tails) sticking out from each scale. Young bark is thin, smooth and gray. Older bark gets thick, furrowed and corky, making Doug fir exceptionally fire resistant. Some Doug firs in dense forests reach for light by growing as tall as 300 feet or more and dropping lower branches, resulting in an irregular, gangly appearance. The oldest Doug firs have been dated at over 1,300 years.

Western redcedar

Red, stringy bark on a trunk that thickens at the base and sends out shallow roots. Flat, overlapping rows of tiny, distinctively scaled leaves emerge in spray-like patterns, often with white butterfly shapes underneath. Tiny cones like rose buds sit atop the branches. Western redcedar can grow 200 feet tall or more in a pyramidal or irregular shape and live as long as 1,000 years. This supremely strong and useful evergreen was the legendary “tree of life” for early Indigenous Pacific Northwesterners, providing everything from wood to clothing to medicine.

Incense cedar

To distinguish incense cedar from western red, zero in on its tiny (about a millimeter) dark-green leaves. Incense cedar leaves have a long, fluted-glass shape, while western redcedar leaves are stubby, rounded and grouped in fours. Another way to differentiate is to crunch the leaves and sniff for the spicy, woody smell of pencils. That’s one way of many that incense cedar wood has been used.

Bigleaf maple

The name says a lot: Big, sometimes huge (foot-wide) leaves grow from a central stem in a symmetrical, five-lobed shape. While it can grow immense, bigleaf maple tends to stay in the 50-foot-tall range with a lush, rounded crown. Definitely not an evergreen, bigleaf maple takes a starring role in autumn’s light show as its leaves go intensely red and gold before dropping. In spring it sprouts groups of tiny, fluffy yellow flowers. Gray-brown bark grows furrowed with age. Seeds are those whirling green helicopters that amuse and delight until somehow they’re underfoot everywhere.

Norway maple

This tree has smaller leaves with sharper, hairlike tips and more prominent veins than bigleaf maple. Norway maple is an invasive species that can be problematic. Popular as an ornamental shade tree on city streets and in private yards, its shallow, dense roots and big crowns can crowd out everything else. (Online commentators call it a “bully tree.”) Some states classify it as a noxious weed, but it’s only on Washington’s Noxious Weed Control Board “monitor” list. Its weak wood is prone to breaking and dropping dangerous, damaging limbs during storms.

Rocky Mountain Glow maple

This colorful, miniature maple grows about 25 feet tall in an oval shape with a trunk just inches thick. Leaves, which go yellow-orange in fall, are triple-lobed with serrated edges.

Oregon white oak

The interrupted history of this regal native says so much about pioneer settlement here. Rounded and shapely with intricate, gnarled limbs when allowed to flourish, the Oregon white oak was encouraged by Indigenous people through controlled burns that kept the landscape open for grazing and for nut and berry bushes. White settlers disrupted that routine, allowing immense, fast-growing firs to replace oak forests. (You can see a long-term oak restoration project now underway at the Oaks-to-Wetlands trail at Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge.) Oregon white oak has rough white bark and rounded, lobed leaves that may turn red or brown in fall. It drops acorns.

Northern red oak

Smaller, darker and smoother than white oak, with pointier leaves and pointier acorns. It turns yellow and red in fall.

Black tupelo

(aka black gum)

The leaves of his tree are darkly glossy in summer and eye-popping in fall with flaming colors. Leaves are simple, pointed ovals, some with serrated edges. The crown is medium sized and flat-topped, and the trunk is gnarled with bark like alligator hide. Although its flowers aren’t terribly noticeable, pollinators like bees and butterflies love this tree.

Persian/parrotia ironwood

A broad, often multi-trunked tree, this packs a rainbow throughout the year. Ovoid, curly leaves evolve from reddish-purple in spring to deep, luscious green in summer to vivid yellow, purple and pumpkin orange in fall. Then, in midwinter, it grows stringy red flowers. With age its smooth gray-brown trunk acquires patches of pink, silver, yellow and cinnamon colors.

Off-list trees

That’s the city’s top-10 list of public trees. Here are a few more signature Pacific Northwest trees that you’ll see both in and beyond Vancouver.

Enlarge

Sitka spruce: Blue-green Sitka thrives along the moist, salty Northwest coastline. This towering tree, which can reach 300 feet tall and 700 years old, resembles a fluffy Doug fir, but you’ll know better after grabbing its stiff, sharp, flat needles, each of which grows from its own individual peg. The thin, jagged-edged cones of Sikta spruce aren’t so friendly, either. Sitka spruce often starts growing out of “nurse logs,” that is, fallen trees. Sitka is famous for its strength and also its sound. It’s used to manufacture pianos, violins and guitars.

Enlarge

Red alder: Our local signature streamside tree can grow nearly 100 feet tall and 2 feet thick. Red alder’s trunk starts out ashy gray; with age, it turns white and becomes pocked with lichen and moss. It has small woody cones as well as long catkins (flower clusters) that pump the air full of pollen in spring. The telltale detail that separates red from other alders is oval, gently serrated leaves that curl under at the edges. Tent caterpillars like to take up occupancy in red alder, but do no damage, according to the Washington State University Clark County Extension.

Enlarge

Black cottonwood: This tree sheds fluffy gauze that seems to have escaped a pillow factory to drift on summer breezes. As a yard tree, black cottonwood gets messy. Thick, heart-shaped leaves turn yellow in fall. Dark, rough bark grows furrowed with age.

Enlarge

Lodgepole pine: Also known as the twisted pine, this coastal tree can grow as tall as 100 feet, or thick and shrubby. Shiny 2-inch needles grow in pairs and sometimes twist in a spiral. Its thin, rough, scaly bark becomes especially tough when growing close to the coast.

What kind of tree goes where?

Tree canopy covers about 19 percent of Vancouver’s total land area, according to a 2021 assessment. The city wants to boost that to 28 percent by 2030.

Why? Because trees are good for just about everything: human health and serenity, the environment, residential property values, even business districts.

“Trees in the community have practical, quantifiable values and are not merely decorations,” Vancouver Urban Forester Charles Ray said. “They provide essential benefits that we cannot live without.”

But not any tree can go in any space. If you’re planting trees on private property, be sure to find out how big they may get and whether they’re likely to grow into conflict with sidewalks, streets, overhead utility lines or any other potential obstructions. (You may need a permit if you’re planting or removing a tree near a street within Vancouver city limits.)

Vancouver Urban Forestry maintains lists of trees that have been approved for streetscapes and recommended for yards as well as trees to avoid because they’re invasive and detrimental (like the deceptively named tree of heaven, which crowds out other trees and adds toxins to the soil).

“Planting the right tree in the right place and giving it the right care and pruning make all the difference to ensuring a healthy urban forest today and for generations to come,” Ray said. “It only takes a minute to improperly prune or remove a tree but a lifetime to grow one.”

Fall is a great time to plant trees, according to the Arbor Day Foundation, because rain and cool temperatures encourage roots to get established, helping your tree weather the hot, dry summer season to come.