Graduating from high school is a great opportunity to indulge in much-deserved celebration. But for some of this year’s standout seniors, their finest moments have come as leaders and support systems for younger students, siblings and classmates.

The Class of 2023 in Clark County is filled with student leaders who, sometimes behind the scenes, help make their school a better place. Club presidents. Aides to school counselors. Charity organizers.

What’s left behind when they graduate is a lesson in what it means to change a life for the better. For schools in Clark County, teachers and administrators hope it’s a legacy that can continue among students for years to come.

Melody Brizuela

School: Prairie High School.

What’s next: Pre-medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Advice: “Follow your passion.”

Enlarge

Taylor Balkom of The Columbian

Few things are more important than a sense of belonging.

In her first few years at Prairie High School, Melody Brizuela wondered if there was a way to bring her and other Latinx students together. Why not create a student union?

“I had to think, ‘What do I want this club to represent?’ ” Brizuela said. “Sure, this is a safe space for us, but we want to share our culture with you all.”

Soon enough, Brizuela had a hand in bringing together another group — the school’s club for students who are Black, Indigenous or people of color, referred to as BIPOC. At the end of the school year, the groups took part in a culture assembly to share music and dance from their respective cultures with the entire school.

In addition to helping uplift their voices, Brizuela saw the group as a chance to set an example for younger students who may carry on leadership of the club at Prairie.

“This year was about passing the torch,” she said. “This is something I wish I had. I know my work isn’t going to waste.”

Melody Brizuela

Brizuela has plenty more on her plate. After an internship at Oregon Health & Science University, she developed a passion for medicine and thought a field in research could help her do more to help the people around her.

Years of hard work all finally came to fruition in one, unbelievable moment this year when Brizuela got her letter back from the one college she’d applied to: Johns Hopkins University.

She was in. And it came with a full scholarship.

“Sometimes it feels surreal, other times I’m overwhelmed,” Brizuela said. “But I’m so excited to meet so many more people like me.”

Cameron Jones

School: Ridgefield High School.

What’s next: Soccer and international studies at the Virginia Military Academy in Hanover, Va.

Advice: “Leave your community better than when you arrived.”

Enlarge

Taylor Balkom of The Columbian

On the soccer field, a center-back has a hand in almost everything that happens. Creating goals, stopping goals, yelling instructions and so forth.

It’s always been a role Cameron Jones has felt comfortable with. But when she tore her ACL as a junior and was resigned to rehab and a spot on the bench, she had to find a new way to be there for her teammates and doubted just how helpful she could be.

“Maybe I didn’t make the impact as a soccer player, but my role on the team in pushing through that struggle, it helped a lot of others,” she said. “I can still be strong, I can still be a competitor.”

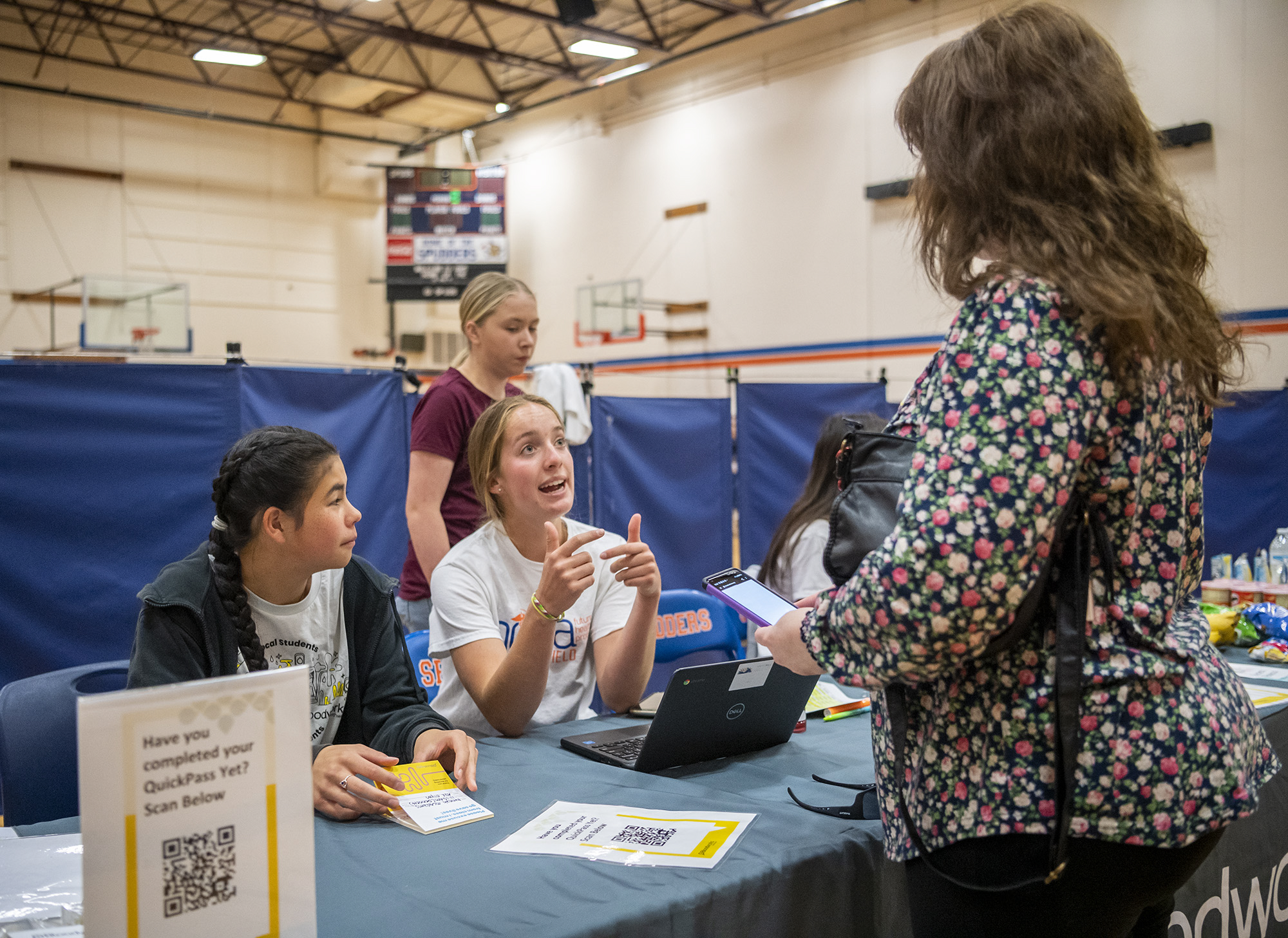

To others, however, there’s no doubt that Jones — whom her teammates later named their “most inspirational player” — is a leader. But on a grander scale, as a leader of multiple blood donation drives at Ridgefield High School, Jones might literally be helping to save lives her in her community.

“Cameron is so invested in our mission, I don’t have to worry about coming up to Ridgefield,” said Lauren Reagan, the community engagement coordinator for Bloodworks Northwest, which provides just about all the blood to Clark County hospitals. “She’s got this whole donor base already established.”

Today, Jones often thinks about what it means to leave a legacy — a hefty concept for a teenager. But it’s something she hopes has more to do with what she’s done for others than herself.

“To the Ridgefield community: I just hope I make you all proud,” Jones said. “This community has done so much for me. Even if it was just one person I impacted, I hope it’s for the better.”

Aundre Pitts

School: Washougal High School.

What’s next: Undeclared at Clark College.

Advice: “Don’t be afraid to go in a new direction.”

Enlarge

Allison Barr for The Columbian

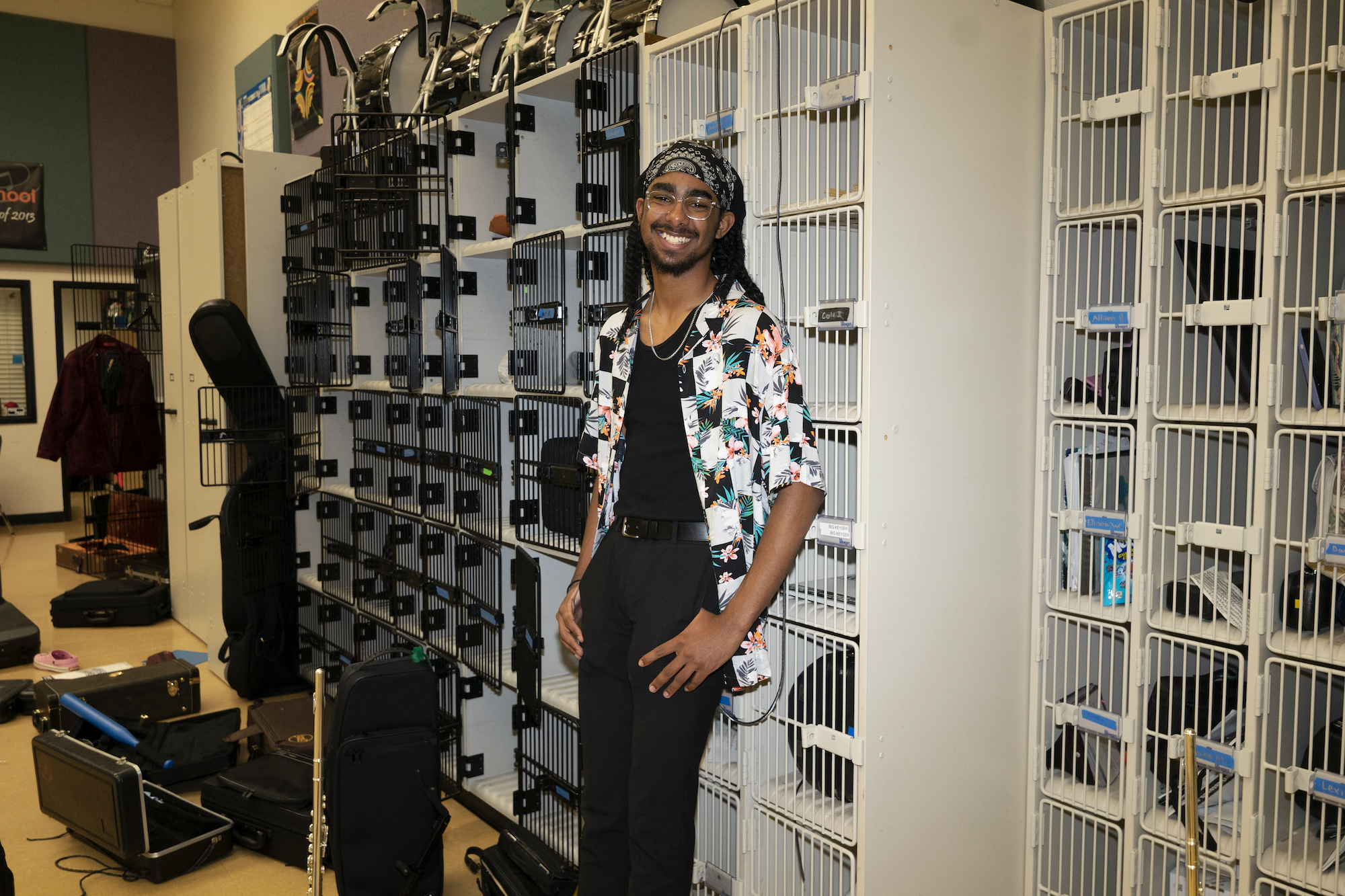

A lot of high school seniors walk with a swagger. They know this is their year.

Aundre Pitts does, too, but he also makes sure that doesn’t get in anybody else’s way.

“As you grow up, people start to look up to you more,” Pitts said. “And I know it’s never fun being that one person who wasn’t included, so I try to make sure anyone can get involved.”

Pitts has become an important leader in Washougal’s music programs as vice president of the band council. Oftentimes, freshmen percussionists — perhaps the most unruly members of any young ensemble — come to Pitts asking for help on a part or a chance to try out a new instrument.

“The percussion students, we can be a little off the hinges, off the rails, but I feel like I’m able to keep them on track,” Pitts said, laughing. “Like my dad’s told me before, ‘if things are hard just keep working.’ ”

The sense of selflessness, Pitts said, comes from his own memory as a younger student sometimes excluded from things by older students or discouraged from stepping outside his comfort zone by friends. As he’s gotten older, he’s made it a point to try new things. Even more recently, he decided to do something he’d never done before: audition for a musical.

After just his first time singing in front of a large group, Pitts was cast in Washougal’s production of “Mean Girls.” The support he saw trying to do his best in a new medium made him understand: the most important thing you can ever do is be supportive.

“It was an enlightening experience. Everyone’s encouraging you to try and get something that you thought maybe you couldn’t get,” Pitts said. “All those new experiences that you go for will allow you to meet new people and develop as a person.”

Claire Jones

School: Ridgefield High School.

What’s next: Soccer, agricultural science and Spanish at Oregon State University.

Advice: “Be you.”

Enlarge

Taylor Balkom of The Columbian

When Claire Jones was younger, she wanted to be just like Taryn Ries.

Those who have been in Clark County for a few years may recall Ries: Ridgefield’s star soccer player who went on to excel at the University of Portland and professionally overseas.

Like Ries, Jones is a known goal-scorer: electric and vocal on the field. Soon enough, parallels started to emerge.

“(Ries) was the talk of the town. And then all of a sudden I’m playing at the same club as her, and then I’m committed, I’m playing in high school, and now girls know my name,” Jones said.

Stuck inside during the COVID-19 pandemic — a particularly jarring time for routine-heavy Jones — demanded she do some self-reflection and create a vision for how she’d continue to stay motivated. What she realized was though it doesn’t hurt to have role models, it’s more important to see yourself as the model of success you want to pursue.

“Not only did I want to stand out as a soccer player, but I realized, no I want to be Claire Jones,” she said.

As her soccer career bloomed into that of a top college prospect, Jones started one-on-one training for younger girls in Ridgefield, many of whom now look up to her. At first glance, Jones looks like a pro trainer, walking students through complex drills centered around fundamentals and muscle memory.

At the core of the training is the same message she tells herself: be you, no matter what.

Next year, she’s taking her talents to Oregon State University, where she’ll also pursue education in agriculture and Spanish. “All in,” she said.

“I try to tell the girls, you do you. I never want them to change their style because of me or anyone,” Jones said. “Everyone wants to be the next celeb or whatever, I think no, you need to be the next you.”

Jaymie Ramirez

School: Evergreen High School.

What’s next: Pre-medicine at Grand Canyon University in Phoenix.

Advice: “Don’t let someone else tell you who you can’t be.”

Enlarge

Taylor Balkom of The Columbian

In the middle of the night when she was a freshman, Jaymie Ramirez realized she needed help. There were bills to be paid, tests to study for, mouths to feed and more. The weight was too much.

Just 14 at the time, Ramirez had spent most of her life in and out of foster care and had just moved in with her stepfather, a long-haul truck driver, and two younger siblings. As the closest thing to an adult at home most of the time, Ramirez was suddenly in the position of essentially raising two young children, not to mention herself.

“Suddenly I’m in charge of three educations,” Ramirez said. “I didn’t know how to get through it.”

In a panic with nowhere to turn, Ramirez called her middle school counselor, who helped her realize Ramirez was experiencing a panic attack for the first time. After some deep breaths and time to think, Ramirez got a referral to begin seeing a therapist regularly to help her talk through the many elements of her now-busy life.

It’s been nothing but a grind ever since: a full load of classes, near-straight-As, a job on the side — all while attending parent-teacher conferences on behalf of her brother and sister. Having seen how mental health struggles, addiction and poverty had stricken her family in the past, she refused to quit.

It wasn’t until she filed her last college application in April that Ramirez took a step back to reflect. She’d made it.

Now ahead of Ramirez lies a chance to start a new life as a college student in Arizona, with the goal of pursuing a career in nursing and helping others, of course, but also where she can finally have a chance to explore who she can be, not who others might need her to be.

“Being a role model is scary, but it’s motivating because I want the best for my siblings just like I want it for myself,” Ramirez. “I want people to know that I won’t give up.”