U.S. Army Corps of Engineers removes enough sand from shipping channel annually to fill Seattle Seahawks’ CenturyLink Field twice

ASTORIA, Ore. — Even for its impressive size, Rice Island barely stands out on a mid-August morning. Approaching the island from upstream, clouds dulled the sun, muting the Columbia River and flattening the landscape’s already monochromatic gray.

Enlarge

Except for a few spots, Rice Island has no trees, no shrubs, no grass, not a single stone — just 250 acres of gray sand.

“A month ago we would have been standing in water,” Neil DeRosier said on Aug. 10 while standing on the island’s plateau several stories above the waterline.

In 2015, the last time Rice was used as a deposit site, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers added 152,000 cubic yards of sand to the island in about two weeks. That’s only a fraction of what’s pulled each year from the Columbia River shipping channel.

To keep the ports of Portland and Vancouver accessible to oceangoing ships, every year the Corps dredges 6 million to 8 million cubic yards of sand from the 107-mile shipping channel between Astoria and Vancouver — enough to fill the Seattle Seahawks’ CenturyLink Field twice. About 1 billion cubic yards have been excavated since the Corps began maintaining the shipping channel more than 90 years ago.

“The thing is, we’re running out of space to put that material,” said Jeffrey Henon, the Corps’ public affairs specialist.

Enlarge

The placement sites the Corps has relied on for nearly 20 years are at or near capacity, so the agency is hunting for new sites to place dredged material or more ways to use it. To the organizations that commodify it, sand is valuable and increasingly sought after. There’s a worldwide shortage of clean sand. And some scientists worry about the environmental consequences of continuing to remove sand from a river system already starved for material.

Beach life

DeRosier builds islands for a living. He is the shore superintendent with the Port of Portland’s Navigation Division, which works with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to maintain the shipping channel at a minimum depth of 43 feet.

He keeps things in a certain perspective.

“I go to work on a boat, then I sit on a sandy beach every day,” he said, while showing off what his co-workers call the “cabana,” a small blue shipping container equipped with an old metal desk and a computer.

“They want to know when I’m going to get a palm tree,” he joked. “We’re thinking of putting a set of stairs up it and a rail around it so I can sit up there in my lounge chair.”

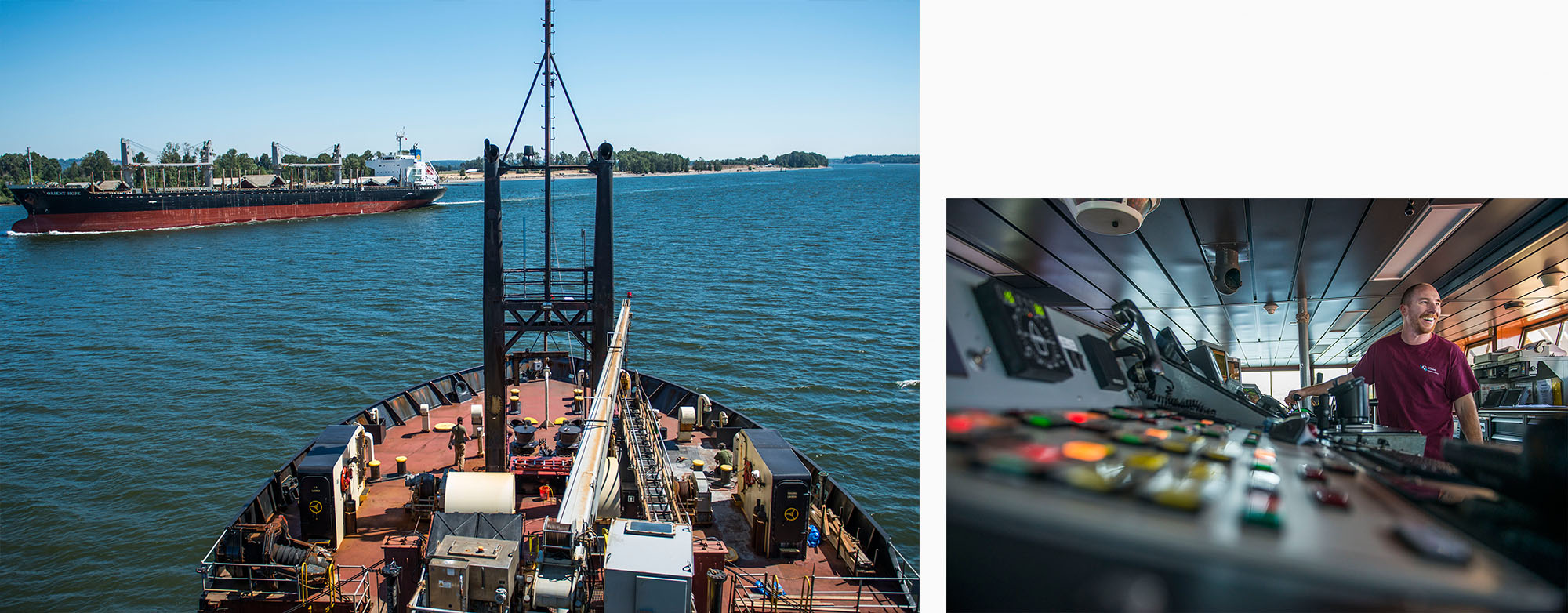

Not far from his office, a knee-high steel pipe runs to the center of the island from the dredge Oregon, floating off the distance. The Oregon, owned by the Port of Portland, functions like the head and motor of a giant cannister vacuum. It is moved by tugboats to a shallow area, where it can use two pilings to “walk” itself around as it works.

The dredge mows down sand shoals that grow in the bottom of the channel. It sucks up to 35,000 cubic yards of material off the channel bed each day, sending a slurry of water and dredge material through a network of pipes around 2.5 miles long to an upland deposit site. Today, it’s Rice Island.

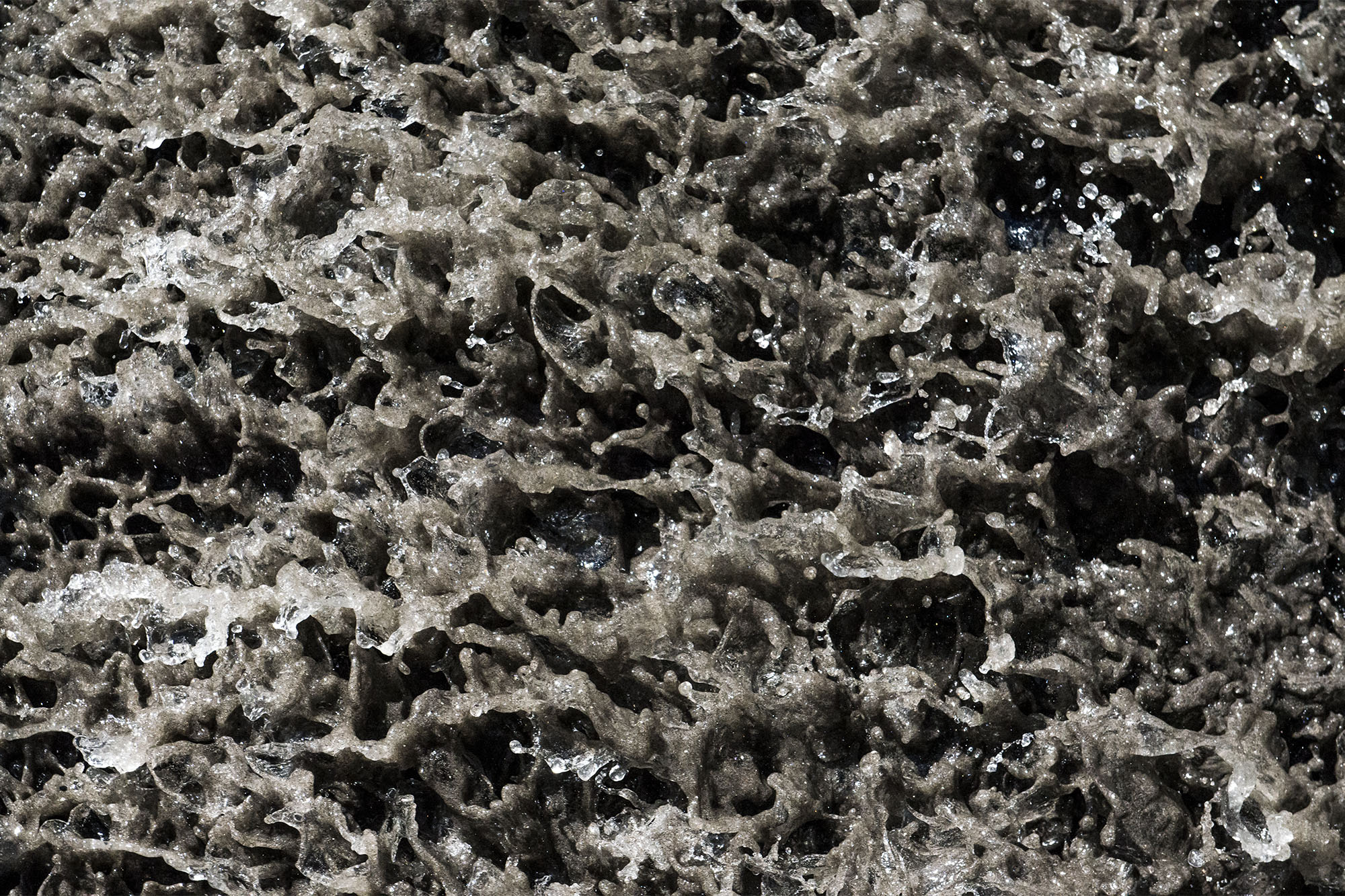

The pipes hiss as gray slurry runs through the pipes and gushes out near the middle of the island. A bulldozer channels it into a tiny river of its own, fanning it out and slowing the flow just enough for the water to release the grit before spilling back into the Columbia River. The process is slow and deliberate, yet the island grows unbelievably fast.

Enlarge

A marine highway

Since 1871, the Portland District of the Army Corps has removed navigation obstacles from the Columbia and Willamette rivers.

The shipping channel facilitates the movement of more than 50 million tons of cargo worth $24 billion each year, according to the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association. The Columbia-Snake River System exports the most wheat and the second-most soy and corn of any shipping gateway in the nation.

In 2017 alone, the Port of Vancouver handled 7.5 million metric tons of imports and exports. The port’s website even touts its upriver location — “closer to the U.S. Midwest and western Canadian destinations than any other West Coast port” — as a strategic advantage.

The shipping channel enables cargo vessels to travel from the Port of Vancouver to Asian ports in about two weeks, making it about half the distance from Midwestern cargo than ports along the Gulf of Mexico.

Enlarge

If the river isn’t deep enough, ships cannot be filled to capacity. That can cost millions of dollars in terms of lost productivity. According to the Waterways Association, in 2012, a grain elevator couldn’t load the last foot of contracted cargo into a ship due to shallow water. It was forced to pay more $60,000 and wasn’t allowed to bid on future contracts.

From April to November, the Corps employs four different dredges to throughout the river to tend the channel, but it’s not long before the shoals return. How big they are and where they’re most problematic depends a lot spring runoff.

Using the sand

Currently, 70 percent of the dredge material is dropped in areas of the river outside the shipping channel; 30 percent is deposited on land. Environmental concerns and transportation costs prevent dredge material from moving too far from its source. So the disposal sites the Army Corps has used for the last two decades are filling up.

The current 20-year Lower Columbia River Channel Maintenance Plan is near its end. The Corps is drafting a new plan in conjunction with the ports of Portland, Vancouver, Woodland, Kalama and Longview. A big part of that work is figuring out where to put up to 160 million cubic yards of sand over the next 20 years. Once sites are located, planners will need to research what it’s going to take to open those new locations — what permits are needed, if land will have to be acquired, and if/when pile dikes in the river will have to be replaced, among other concerns.

Corps officials said they try to use the sand beneficially when possible, including habitat construction for salmon and for streaked horned larks, a subspecies the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says “may be the most endangered bird in Washington.”

Enlarge

“Their habitat was sandbars shifted around by giant Columbia River floods,” said Jarod Norton, project manager for dredging of the Federal Navigation Channel at the mouth of the Columbia. “Dredging mimics that because we create sandbars that we’re moving all the time. … We create sandbars, then they come in an nest.”

Norton said the Corps is looking to use more of sand for habitat creation, but there are some challenges. It’s hard to find partner organizations that have money and can handle working with large volumes of material.

“Other smaller opportunities are too small for our time,” he said. “The cost of mobilizing a dredge and setting it up is too expensive.”

Earlier this year, the Army Corps’ headquarters in Washington, D.C., issued a request for proposals for pilot projects that could use dredged materials from the Columbia River and other navigation channels in beneficial ways.

Under, a 2016 law, the Corps is required to carry out 10 projects that could be related to storm damage reduction; restoring and creating aquatic ecosystems; recreation; enhancing shorelines; civic improvement; and others. Those proposals were then forwarded down to regional offices for review.

The Portland District evaluated fewer than 10 projects. Most were similar to those the Corps has reviewed in the past, Norton said.

The assistant secretary of the army for civil works will decide which projects make the final cut. Those will then be sent to Congress for evaluation.

Local applications

The clean, uniformly gritty sand that comes from the shipping channel has a lot of potential applications. Astoria uses it as a filter media in its sewage treatment plant; it’s used as aggregate in concrete blends; developers use it for fill material. Because sand drains better than clay soil, it’s useful for lawns.

The Port of Vancouver uses it for its own projects — Terminal 5, the Centennial Industrial Park and Columbia Gateway property among them.

The Port of Woodland, which operates two sites, is one of the few that also sells it.

Four years ago, the port was filling up and under pressure to get rid of the sand. But now, a regional construction boom is putting it in high demand. About 400,000 cubic yards of the port’s sand went into building the Cowlitz Tribe’s ilani casino and the La Center freeway interchange.

“They got it all in about 13 to 14 months because construction was going gangbusters and they needed the sand for fill,” said Jennifer Keene, executive director of the Port of Woodland.

Enlarge

Keene expects to see a continuing demand. In a recent survey of local markets, she tracked mason sand selling for up to $42 a cubic yard and river sand selling for up to $28, which she described at “extraordinarily high.”

“It is a prized commodity coming around this year because there’s so much construction happening and in the Pacific Northwest you have to fill,” she said.

The Corps doesn’t own the sand, the states of Washington and Oregon do. When the port sells the sand, it pays a royalty to one or both states, depending on which side of the river it came from.

When all the costs were deducted, the port netted about $1 million on sales of 685,000 cubic yards.

Private businesses also receive and sell the dredged material.

Richard Fazio, co-owner of Fazio Brothers Sand, runs a 17-acre deposit site in Clark County. The site has been continually in use since the 1950s.

He too said the sand is in high demand.

His clients have included school districts and the University of Portland, Oregon State University, and other college, all of which use it on their athletic fields. He’s also sold sand to a number of golf courses.

“In this area, where we get a lot of rain, the water percolates away and out of the field so they can keep playing on it without getting muddy,” he said.

He typically sells around 90,000 cubic yards per year. He’s had offers to move much more, but it’s not in his business plan.

Enlarge

“My thought it we want to be in this for the long term,” Fazio said. “I’m not trying to sell all the sand in he world, just enough to keep us busy.”

A rare commodity

At the global level, humans are digging up more sand than the environment can produce.

In 2014, the United Nations Environment Program published a paper titled “Sand rarer than one thinks.”

The report explains that “sand and gravel account for the largest volume of solid material extracted globally. … They are now being extracted at a rate far greater than their renewal. Furthermore, the volume being extracted is having a major impact on rivers, deltas and coastal and marine ecosystems results in loss of land through river or coastal erosion, lowering of the water table and decreases in the amount of sediment supply.”

The Columbia River is unique in that sits atop a rising tectonic plate and cuts through a hard rock environment, rather than meandering through its own sediment as do the Mississippi and other large rivers.

Portland State University Professor David Jay said the lower Columbia River has had a sand deficit since 1962.

He and a colleague published a 2013 paper about the issue, “Lower Columbia River Sand Supply and Removal: Estimates of Two Sand Budget Components.” In it, they argue the river needs a certain quantity of sand for estuary habitats for salmon and other wildlife, the function and maintenance of the navigation channel, limiting coastal erosion and the stability of the jetty system at the mouth of the river.

Enlarge

“The (Columbia’s) sand deficit documented here has likely contributed to the lower water levels in the tidal river observed in recent decades, which decreases habitat availability during high flows and channel depths during low-flow periods,” the report states.

In a recent interview, Jay said a combination of sand mining, dredging, climate change and flow regulations by dams have all combined to mean more sand is removed from the river than nature puts in. The dams alone choke off around 70 percent of the sediment that would otherwise flow into the lower Columbia, he said.

“The other really big reason why I think we’re seeing the water level changes is the more streamlined channel, the more hydrologically efficient the channel is,” he said. “The Columbia is now twice as deep and half as wide in a lot of key areas.”

The biggest historical problem he see with the creation of the navigation channel was the silting of salmon habitat and historical use of dredge materials to fill wetlands.

“If there weren’t dams and people weren’t involved, sand would come down from mountains and form a big ebb delta,” said Curtis Roegner a fisheries biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “But what’s happened, we’ve channelized the river and cut off the big flows so there’s not nearly as much force pushing the sand out, plus we want a deeper channel for shipping. The end result is the beaches don’t get enough sand and they’re eroding.”

He’s studying how the Corps’ sand disposal methods affects wildlife near the mouth of the river and how much sand is making its way back to the beaches.

He’s also looking into a project that will examine if the sand islands the Corps creates in the shallow intertidal zones could be engineered to have a mix of habitats for a variety of creatures.

“They created a whole bunch of islands from dredge spoils, but not in a manner to enhance certain aspects of the ecosystem, they just piled it up. We want to do a focused design,” he said.

Onboard the Yaquina

Enlarge

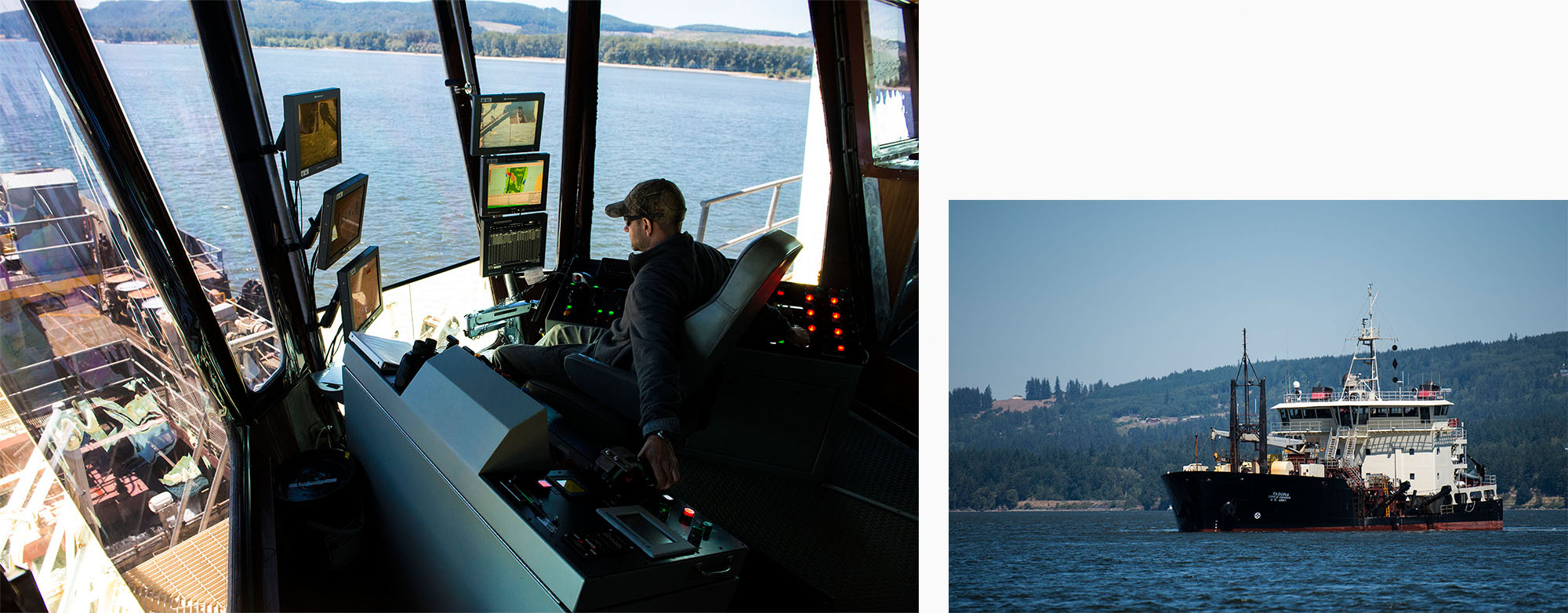

If the dredge Oregon were a canister vacuum — big, cumbersome, yet effective once set up — the hopper dredge Yaquina is more like a handy vacuum — light, mobile and ideal for hard-to-reach places.

“They like us because we can go into those spots,” Crew Master Jon Blake said. “They’re running out of places to put (the sand).”

Blake has worked on the Yaquina for about 30 years. Electronic ranges, GPS systems, cameras, and other technology have enabled the Yaquina to dredge accurately within 6 inches — even with its arms extended to 45 feet.

Unlike the Oregon, the Yaquina is a ship. At 200 feet long, nearly 60 feet wide, and 100 feet tall, it was built to get in and out of tight places quickly, though it’s vulnerable to rough ocean waters.

The vessel works up and down the West Coast, working in seas that sometimes toss sleeping crew members from their bunks — a stark contrast from the six or so weeks they spend on the Columbia River each year.

“Working in the Columbia is very pleasant. Everyone’s sleeping good, eating too much — keeping our food down too much,” Second Mate Joey Minnick said. “The river’s awesome; it’s so predictable. Even if we have shutout fog and I can’t see my hand, we’re going to dredge.”

The Yaquina can handle up to 1,000 yards of sand at a time, sucking it up through two drag arms — they resemble steel vacuum hoses with a paw-shaped attachment — in about 45 minutes, then dropping it in shallow areas other dredges can’t reach.

The ship works kind of like a street sweeper in a busy road — darting in an out of shipping traffic to mow down the shoals, a practice that is hard for some merchant mariners to get used to.

“The other day a 600-foot chemical tanker was in the middle of the channel. My training teaches us to stay away, turn away, go away,” Minnick said. “But my needs here say aim right at him, wait until he’s across the channel, then accelerate toward him so right when he passes I can spin and plop my drag arms down and keep digging. Try to teach that to a new mate. They think accelerating toward the chemical tanker is a terrible idea!”

Enlarge