After Barbara Hilenski and her family were evicted from a Vancouver apartment complex in May, their world shrank down to one room — a motel room.

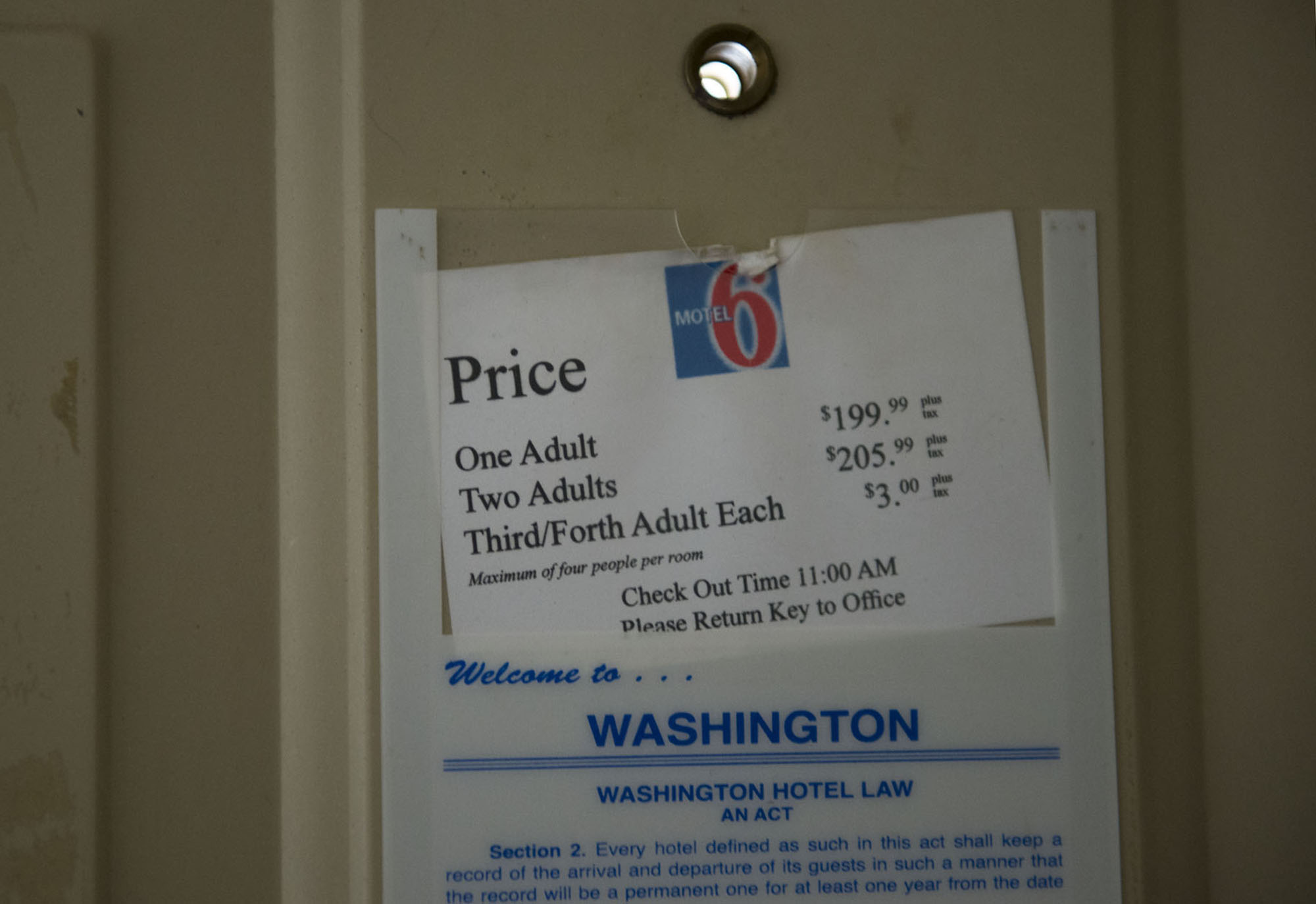

First, they stayed at a Quality Inn. Then they moved into the Motel 6 in Woodland.

There, in a small room with two queen-sized beds, Hilenski has lived since July with her long-haul-trucker husband, their two younger children, an energetic black Lab and an irritable cat. One room for cooking, sleeping, home schooling and hanging out. Their belongings are in storage.

It’s close quarters, but the Hilenskis don’t have many options. Al Hilenski’s truck-driving job, which keeps him on the road to Los Angeles and back Monday through Friday, covers their $1,053 monthly rent and meager expenses. They live week to week, and the only government assistance they receive is food stamps. Everyone pitches in to keep the room immaculately clean.

They could afford an apartment, but with an eviction on their record, a Chapter 13 bankruptcy and bad credit, combined with Clark County’s critical lack of affordable housing, no one will rent to them, Barbara Hilenski said. She said they were kicked out of their apartment after five years when the family took the apartment owner to court over a black mold problem that was making them sick with skin infections and lesions.

Now, the family is in limbo. And privacy is a thing of the past.

“I used to go, ‘Hey, if you kids aren’t killing each other, don’t bother me,’ ” said Hilenski, 55, a wiry, animated woman with a mane of curly hair. “We just make it work.”

She takes walks with Rocky, the dog, so she can think.

Emily, 13, and Jeremiah, 15, have been homeschooled more than three years by Hilenski, who attended high school in San Jose, Calif., but didn’t graduate.

Hilenski pulled the kids out of public school due to issues with bullying. Also, “the homosexual thing is getting pushed down their throat,” said Hilenski, a born-again Christian who feels it’s her duty to share the Gospel. But she feels isolated.

“If it wasn’t for the Lord, I probably would’ve blown my brains away. Don’t think I don’t think about it,” she said.

We don’t have savings. We don’t have nothing. We sacrifice. Barbara Hilenski

They don’t leave the motel much. Most days, when Emily and Jeremiah have finished their lessons, they sit on the beds playing video games and watching TV. Sometimes they rent movies, but the family keeps a tight handle on the money. They celebrated Emily’s birthday with lunch at McDonald’s and a trip to Horseshoe Lake.

“We don’t have savings. We don’t have nothing,” Barbara Hilenski said. “We sacrifice.”

The Hilenskis’ 18-year-old daughter, Hannah, a senior at Evergreen High School, has a job and often stays with friends. Hilenski wants to scrape together the money to buy a fifth-wheel trailer and leave town, somewhere high and dry, where the mold and allergens won’t bother her. Because Al Hilenski has a commercial drivers license, they could go anywhere, she said.

But the couple wants to wait until Hannah graduates high school.

Even though it’s a struggle, Hilenski, who grew up in foster care, is glad the family is together. She tells her children, “You are better off because you have a mom and you have a dad.”

Amy M.E. Fischer: 360-735-4508; amy.fischer@columbian.com; twitter.com/amymefischer