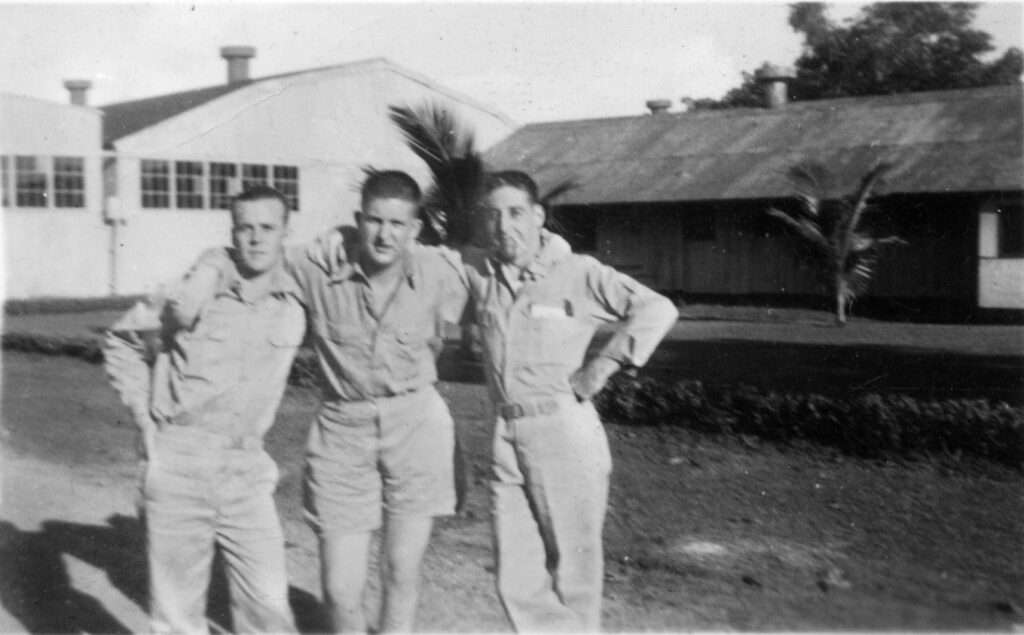

La Center kid Herb March was 21 when he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1939. He wasn’t much older — just 24 years old — when he died of malnutrition and disease in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in the Philippines during World War II.

Eighty-two years later, March’s surviving relatives welcomed him to his last resting place with joy, sorrow and wonder. In early May, accompanied by military escort, March’s remains were flown from a lab in Hawaii to Texas and then to Portland International Airport. The following day, March was interred alongside family at a Woodland cemetery during a highly ceremonial military burial.

“It was nothing less than completely amazing. It was so emotional,” said Kay Cooke of Ridgefield, March’s great-niece, who played a key role in connecting military forensic experts with a surviving, elderly March cousin in order to match DNA samples.

Enlarge

James Rexroad for The Columbian

Identifying the remains of unknown soldiers has leapt forward since the 1990s due to advancements in science, according to Sean Everette, spokesman for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. But it’s still slow, painstaking work thanks to underlying problems, including haphazard historical documentation and partial remains mingled in common graves, Everette said. Some remains — such as those lost at sea or in acidic soil — can never be identified.

The remains of 64 U.S. military personnel have been positively identified during the current fiscal year (July 2023 through June 2024), according to the agency’s website. Meanwhile, upwards of 80,000 are still missing overseas from conflicts dating as far back as World War II. It’s estimated that about half might ultimately be identifiable and recoverable.

“Our job will never be done, unfortunately, but it’s worth doing,” Everette said. “The advent of DNA (analysis) has allowed our mission to open up much wider. We are committed to continuing the mission.”

Common graves

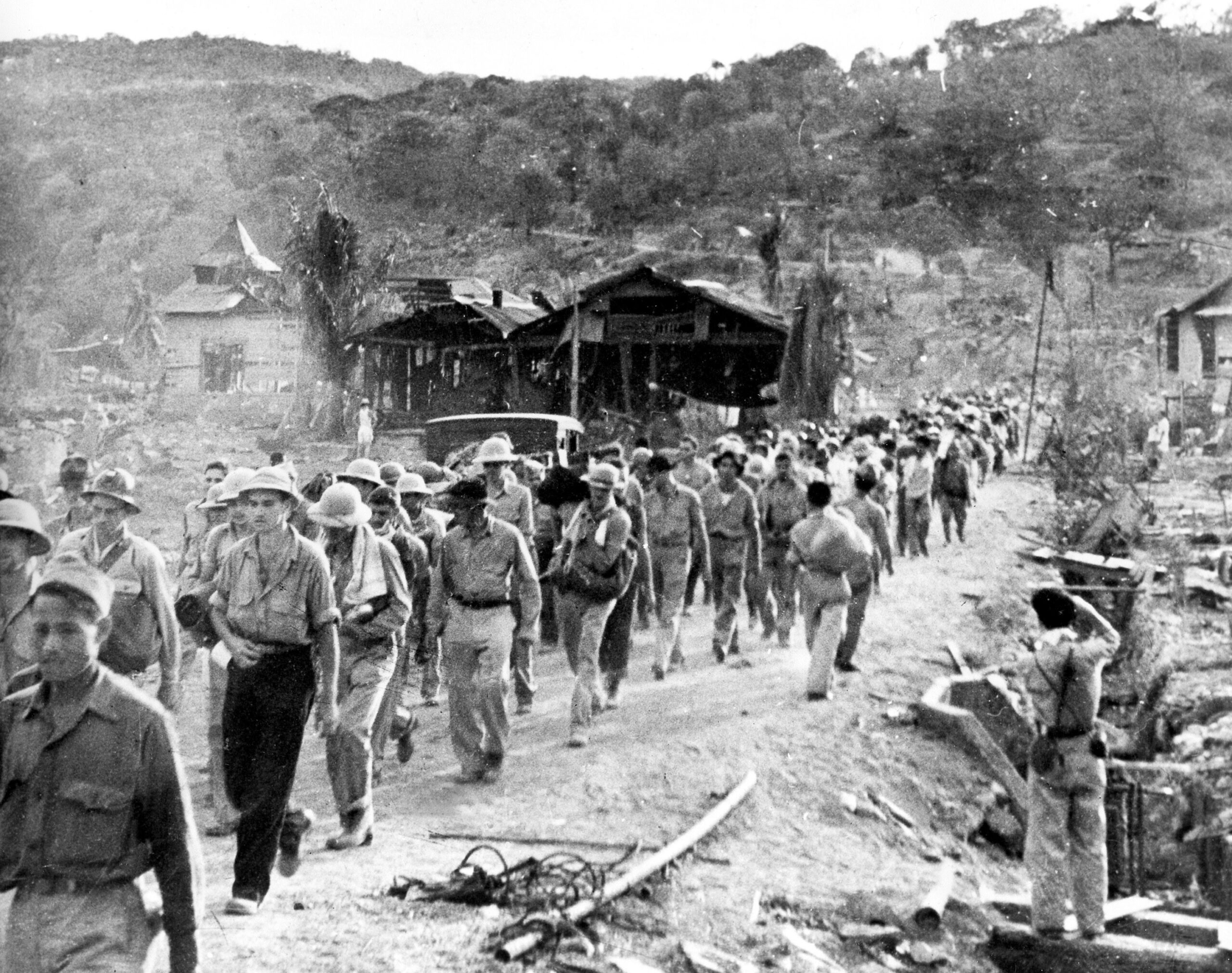

According to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, U.S. Army Air Forces Technician Fourth Grade Herbert F. March was captured in the Philippines in April 1942 as U.S. forces surrendered on the Bataan peninsula. He was then forced to walk 65 miles through the tropical jungle in what’s now referred to as the Bataan Death March because many prisoners didn’t survive it.

March survived the jungle slog but not its destination. He died just a few months later, on July 26, 1942, at the notoriously overcrowded Cabanatuan POW Camp No. 1 in the north Philippines.

“He survived the march only to die, or be helped to die, of dysentery,” Cooke said. “He was then tossed like a rotten apple in a common grave with others.”

Enlarge

Associated Press files

“At its peak, Cabanatuan held approximately 8,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war,” according to a narrative on the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency website. “Conditions at the camp were poor, with food and water extremely limited, leading to widespread malnutrition and outbreaks of dysentery.”

Camp records note the date when March was admitted to its hospital and that he ultimately died of “illnesses.” Tragically, he was just one of thousands.

“So many people died in that one camp, they were all buried in common graves,” Everette said. “All who died on the same day, they were buried in the same grave.”

There’s no conclusive tally of how many prisoners were buried that way. What is known is that March’s demise added to the single worst monthly death toll at Cabanatuan in July 1942, when 799 U.S. prisoners died there.

After the war, the U.S. disinterred all those remains and identified just three. The rest were judged unidentifiable and reinterred at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial.

And that was the end of the story until March 2018. That’s when all remains from Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery Common Grave 225 were exhumed and transported to a military lab in Hawaii for possible identification, Everette said. That included DNA samples that were forwarded to yet another lab in Dover, Del., in search of family matches.

“Forensic anthropologists go over all the remains. They catalog them all,” Everette said. “A lot of remains from CG 225 were co-mingled, so it’s like working on several jigsaw puzzles at once, with the pieces all mixed up together.”

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency finally confirmed March’s identity Aug. 10 by matching his DNA to a sample supplied by a cousin here in Southwest Washington. That only happened thanks to Cooke.

Enlarge

Taylor Balkom of The Columbian

Family man

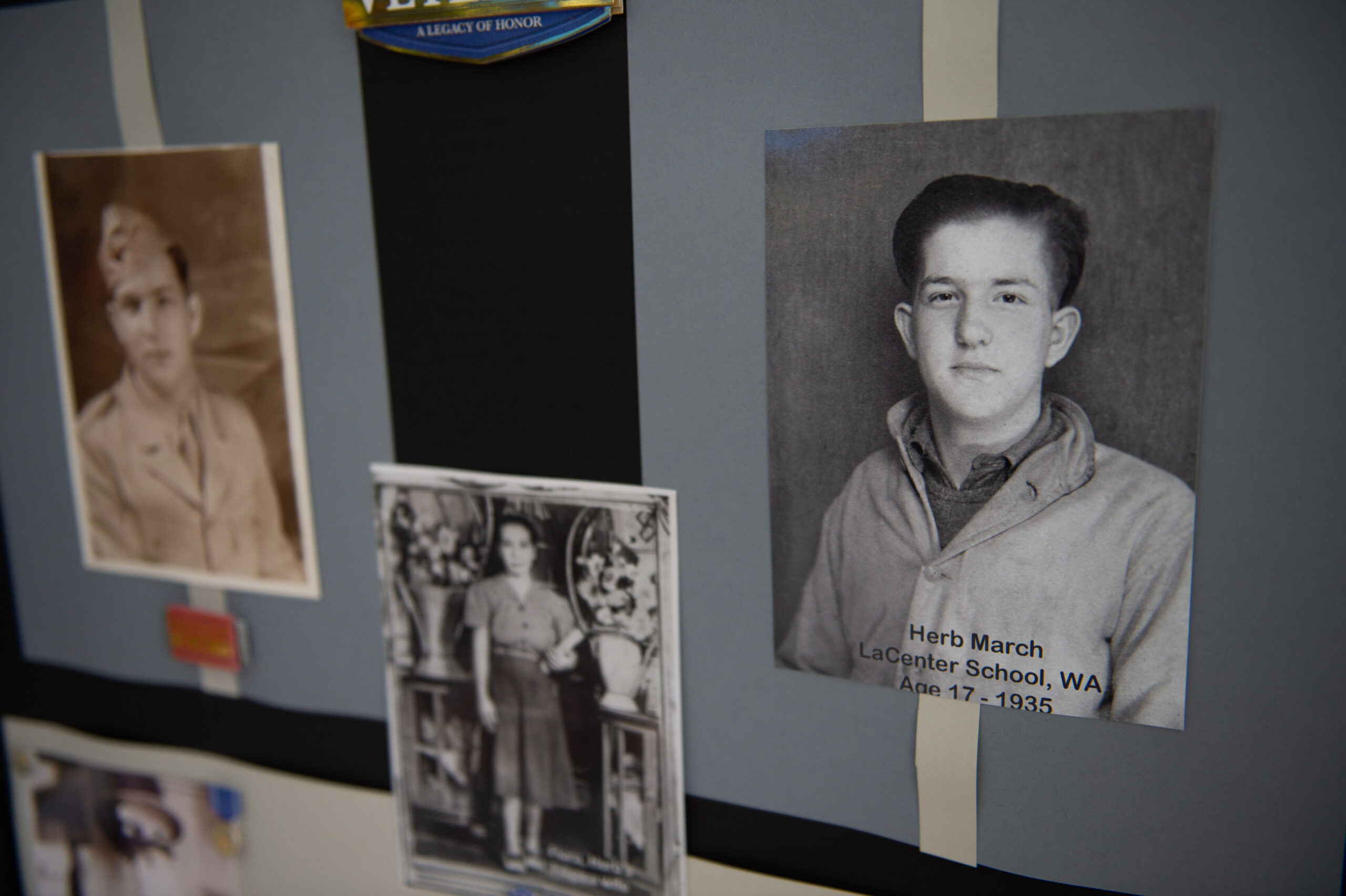

Cooke never met her Great Uncle Herb and can’t claim to know much about him.

“Just bits and pieces,” she said. “You know, when your parents tell you stories about your relatives, you sort of ignore them until you’re ready to hear them.”

But she does remember her father’s strong feelings about the family’s loss, she said.

“My dad, Jesse Wills, was Herb’s nephew. Dad would talk about the loss of Herb and how they knew nothing. It made him both sad and mad,” she said.

Cooke assumes March must have been proud and patriotic like her own father, who couldn’t serve in the military because he’d lost an eye in a BB gun mishap as a youth.

“I remember my dad wanted so badly to serve in the war,” she said. “The Army wouldn’t take him, so he wound up a Merchant Marine and he was so proud. I think patriotism really carried through the generation that was serving in World War II.”

Enlarge

James Rexroad for The Columbian

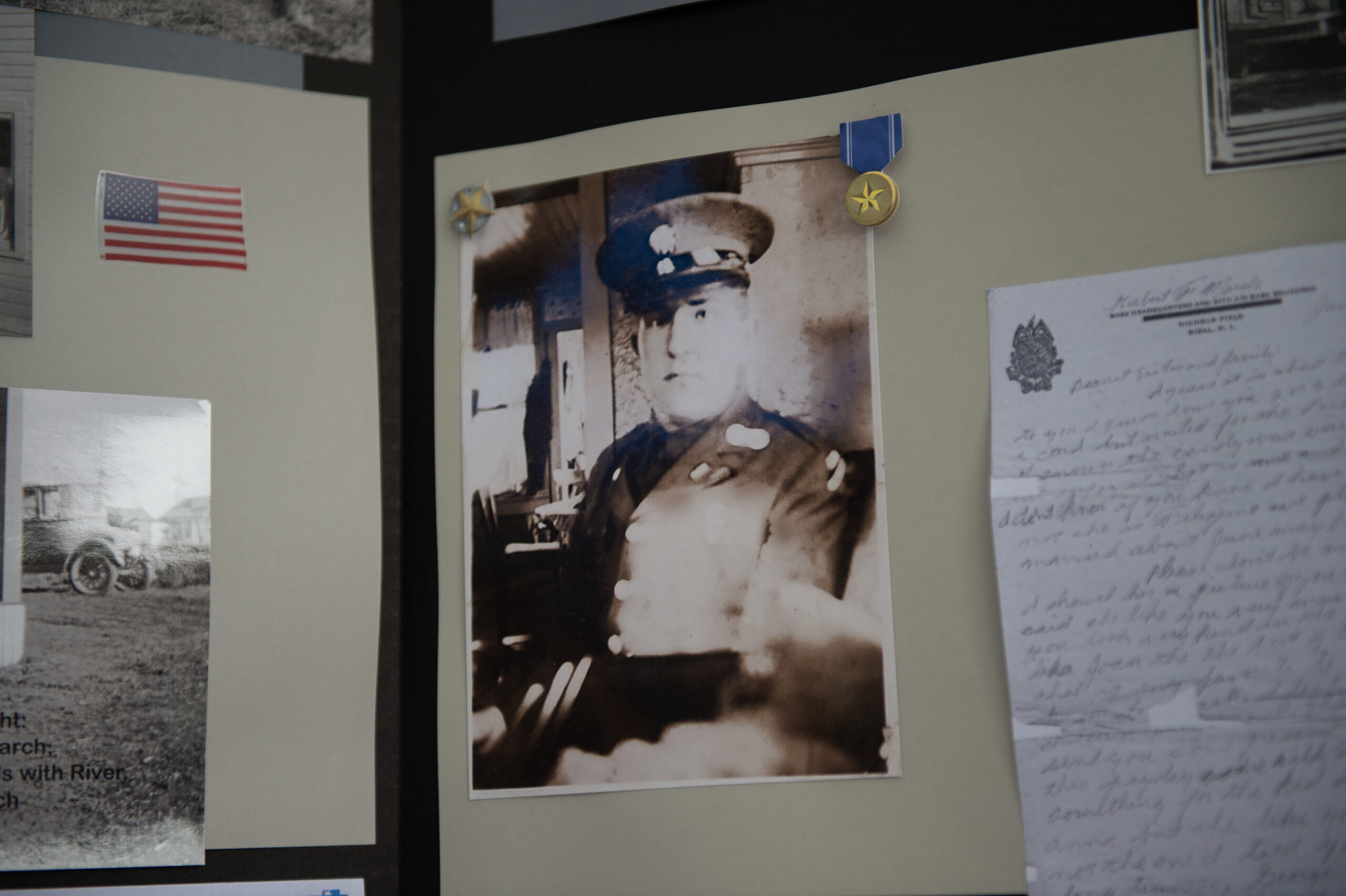

Cooke does have a handful of letters that March wrote home from the Philippines in the late 1930s. His letters give the impression of a loyal, loving, family-oriented man more accustomed to farm and forest labors than to reading and writing.

“They were country people and they were poor, but everyone was,” Cooke said.

“I don’t know if you know I have a girl or not,” March wrote in January 1939. “She is Filipino, we plan to get married. … Please don’t be mad sister, I showed her a picture of you and she said she like you very much because you look very kind in the face.

“I forgot to tell you … my girl believe in God very much and now she has got me believing too.”

“I’m not worried, I and Flora are OK and feeling fine,” he wrote later the same year, signing the letter “from Herbert and Flora.”

Enlarge

James Rexroad for The Columbian

After March’s death and the war’s end, Flora sent several warm, loving letters in 1946 to March’s mother, who was now Anna L.M. Boucher and living in the Columbia River Gorge town of Cook.

“I celebrated Christmas with sorrow and pain,” Flora wrote. “Simply because my dear husband is not with me. But Mother, you will be proud to say that ‘My son died for the common cause.’ I hope you may live the better moment of every day and have a happy and a (pious) life.”

It’s unknown what happened to Flora after that.

The military file that Cooke and her family eventually received also includes polite, regretful dialogue between forensic investigators and March’s mother in the late 1940s and early 1950s, regarding physical characteristics (such as dental records) that could help identify his remains. But that never happened while Boucher was alive.

Enlarge

Taylor Balkom

Family project

Cooke wasn’t ready for such a tough and seemingly remote story when she was little. But nowadays, she’s an incurably curious genealogical researcher and publicist for the Clark County Genealogical Society. When her Great Uncle Herb’s story unexpectedly found her, a few years ago, Cooke eagerly dug in.

“In 2017, I get a call from the Army,” she recalled. “‘We are trying to trace the oldest family members of Herbert March.’”

It was actually the Army’s second attempt to track down a March relative — because nobody had responded the first time — but it was news to Cooke, who agreed to take a DNA testing kit directly to an elderly aunt named Donna June Cline, get a sample and mail it right in.

“We didn’t hear anything for the longest time,” she said. Meanwhile, Cooke’s cousin Ronald Bryant of Woodland became Cline’s guardian. When the Defense POW/MIA Accountability Agency finally reached out this past January, it was Bryant who received their message: Positive ID had been made. Herbert F. March would soon come home. And where did the family want him buried?

The answer: Woodland.

“We have a lot of family buried there already,” Cooke said.

Even the military escort that accompanied March’s casket on its journey to Portland kept the project in the family: It was U.S. Army Col. Robert Bryant, Ronald’s son, who is stationed in Hawaii.

“My aunt gave the DNA. The nephew escorted his great-great-uncle. I am in awe of all this,” Cooke said.

Color guard members stand at attention as a casket containing the remains of U.S. Army Air Forces Technician Fourth Grade Herbert F. March of La Cente, is unloaded on a rainy Saturday in May at Portland International Airport; Passengers on American Airlines Flight 2496 watch out their windows as the remains are unloaded May 4; Soldiers and airport personnel carefully move the casket; Ann-Mari Bryant, March's great-great-niece, wipes a tear from her eye as March’s remains are unloaded at the Airport; Family members record the moment March's coffin is unloaded; Kay Cooke of Ridgefield, center, watches with other family members as the remains of her great-uncle are unloaded from an American Airlines flight at Portland International Airport; Relatives watch as March's casket is loaded into a hearse; Volunteers with the Patriot Guard, an organization that provides honor guard and escort for military and first-responder funerals, join a procession carrying the remains to Kelso;Bryant, left, and Cooke regroup in a van after a solemn military ceremony at the tarmac at Portland International Airport; A hearse carrying the remains leaves Portland International Airport. (Photos by Taylor Balkom of The Columbian)

Final rest, family reunion

While the military kept Cooke informed of that May weekend’s arrangements, she still wasn’t prepared for scale of pomp and ceremony. Police, fire trucks and an honor guard met the plane on the tarmac at PDX. A long convoy of vehicles, led by Patriot Guard volunteers on motorcycles in missing-man formation, led the way north to a funeral home in Kelso.

“The weather was nasty, and I felt so bad that they were out there in the rain,” Cooke said. “But they just said it was their privilege and their honor.”

Along the way, Cooke said, she watched the driver of a pickup on the freeway notice the convoy, pull over, get out of her car and stand at attention with a white cowboy hat placed over her heart.

At the funeral home, Cooke said, the casket was opened for final inspection, revealing an empty, decorated military uniform. Herb March’s actual remains were securely wrapped below that and could not be seen, she said.

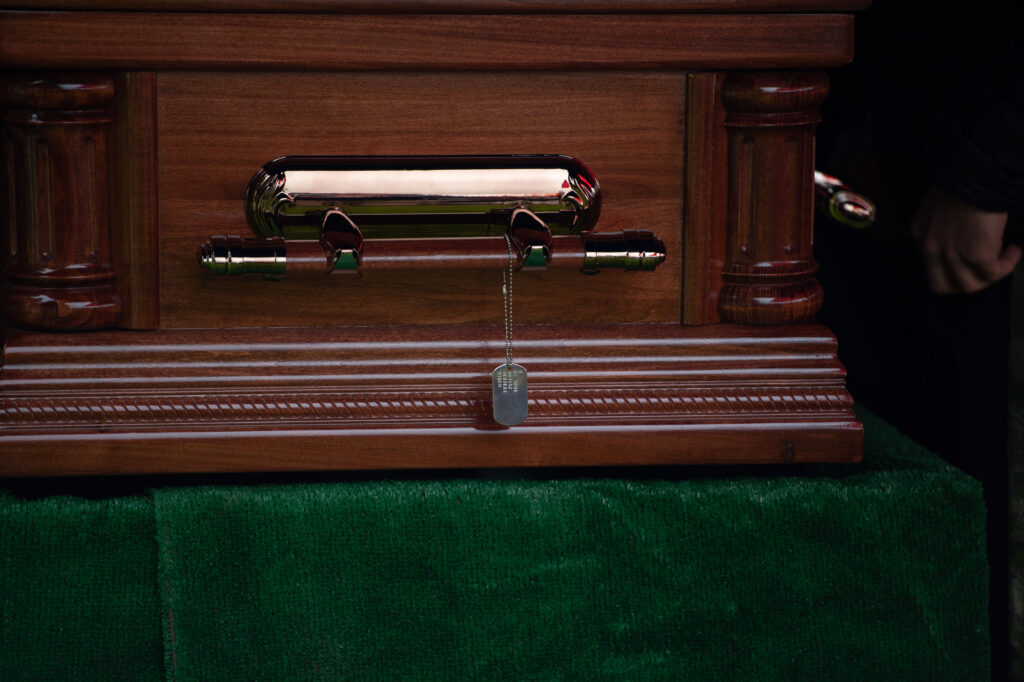

Photos from top (left to right): The casket of Herbert March of La Center, a U.S. Army Air Forces technician, is moved from the hearse to its final resting place at Kerns-Bozorth Cemetery in Woodland; the posthumous Purple Heart awarded to March; March’s dog tag hangs from the side of his casket at the funeral; Ronald Bryant, center, and David Bryant, right, look at memorabilia of the life of Herbert F. March, their great-uncle; Members of the Patriot Guard motorcycle club witness the internment of Herb March's remains; None of these family members ever met March, who died in the Philippines in 1942, but they were moved by the return of his remains after many decades, and his May 5 military burial at Kerns-Bozorth Cemetery in Woodland. (Photos by James Rexroad for The Columbian)

After all that, Cooke said, the May 5 burial service, conducted by an Army chaplain, was ceremonial but brief. Col. Robert Bryant was presented a folded-up flag, which he then presented to his father, Ronald. There were three bursts from honor guard rifles and mournful music from a military bugler.

“I’ve never heard anybody play taps as beautifully,” Cooke said.

After that, she said, most of the funeral party — including reunited family members and new military friends — went to lunch at Woodland’s venerable Oak Tree Restaurant.

And that’s perhaps the most beautiful aspect of this sad but heartwarming story, Cooke said: It pulled together 20 or so members of her extended, scattered family.

“This is the first time in about 50 years that some of the cousins and other relatives have seen each other,” she said. “It was really, really special. There were tears of sadness and tears of joy. It has brought back to me so many people who were missing in my life.”