Columbia River Gorge town’s residents happy to support monastery’s Theravada Buddhists, their quiet spirituality

WHITE SALMON — Two monks clad in orange robes padded quietly through a sun-dappled forest on an April morning. Wild turkeys meandered the hillside as the pair walked single file along a dirt trail and down a pothole-filled road past a park and a ranch.

In a country where monasticism is rare, it is an unusual sight. But not in White Salmon. For about nine years, the Thai Forest Buddhist monks at Pacific Hermitage have maintained a tradition of walking through the Columbia River Gorge community for alms, or food offerings.

“It’s sort of just become part of our town that you see them out walking every morning,” said Colleen Regalbuto.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

The 40-year-old White Salmon resident described the monks’ relationship with the community as symbiotic. They provide meditation training and teachings at a local yoga studio. In return, she’s happy to be among a group of people supporting them. Just being near people who have dedicated their lives to contemplation is inspiring, she said.

The monks at Pacific Hermitage are mendicants, dependent on whatever food is freely given to them. During their daily alms rounds, the monks may stop at someone’s house or meet people in town or at the hermitage, or they may pick up food that’s been ordered for them from a restaurant, such as the North Shore Cafe.

Cafe owner Amber Nelson, 36, has developed a relationship with the monks, cooking healthy food from scratch.

“On a weekly basis, we get phone calls from people all over the United States calling in orders for the monks,” she said. “It’s amazing how the energy is lifted when they come in the cafe at 9 a.m.”

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Most of the people who offer food are not Buddhists. According to Pew Research, 1 percent of Washington residents are Buddhist. Most Washingtonians say they are unaffiliated with any religion, or associate with no religion in particular.

The monastery is strategically located on 10 forested acres not far from town.

While walking down Barnedt Road, Ajahn Sudanto, the hermitage’s Vancouver-raised abbot, stopped to admire a rare chocolate lily. Daily walks through the forest give him time to notice small changes, to observe nature’s cycle of birth and death in real time. Ajahn Kassapo walked quietly behind him. They carried stainless steel alms bowls wrapped in crochet.

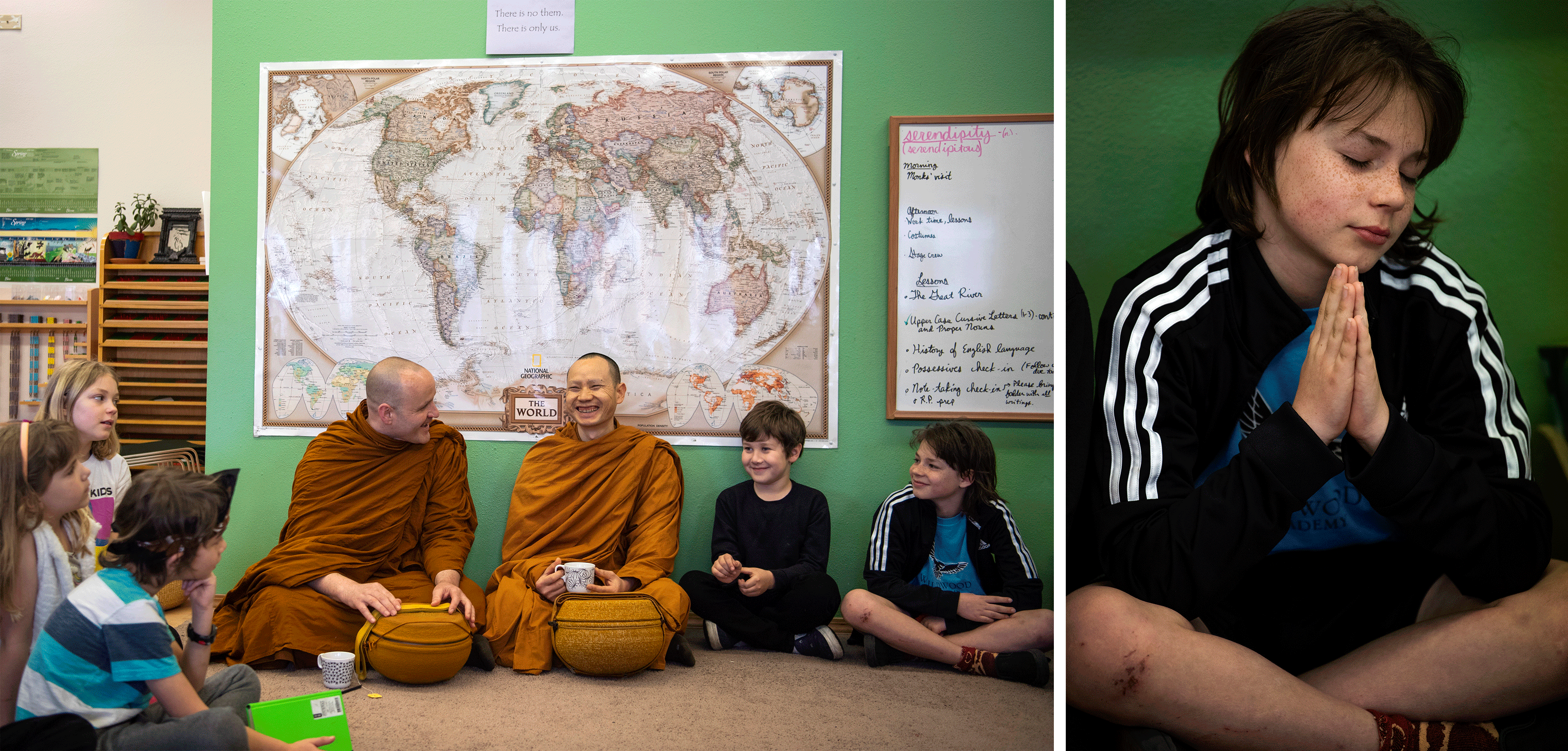

On Fridays, they visit Little Oak Montessori School.

“The monks are here!” several children exclaimed as they entered the school recently. Two girls swiftly assembled a tea tray.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Everyone sat in a circle on the carpet as Sudanto, 50, told them about his recent trip to Japan.

“All the cherry trees are in blossom and there seems to be this whole culture of just appreciating them,” Sudanto said. “People are going up and smelling them on these days. They’re taking pictures of themselves, doing selfies in front of the cherry blossom trees.”

Lead teacher Allison Lide suggested the class commemorate the monks’ return by going in a circle reciting a virtue.

“Maybe it’s the virtue that you like to see most in other people,” she said.

The kids rattled off the virtues they value: joy, responsibility, love, compassion, equanimity, peace, kindness, creativity, respect, hope, gratitude, fairness, happiness.

“Do I get to have one?” Sudanto asked. “I’m going to pick goodwill. Sometimes we translate that virtue as love and kindness or love and friendliness. It’s just this absence of any kind of ill will.”

Besides goodwill, the virtues of the Thai Forest tradition, a branch of Theravada Buddhism, include discipline, renunciation, inner truth and peace and living a life of simplicity. Monks cannot possess or use money. They cannot ask for food or store leftovers.

“The Buddha talks about the monks not being hermits in the sense of totally withdrawing and not being visible in the community,” Sudanto said. “You are in relationship with — preferably daily contact with — the rest of the community.”

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Connection

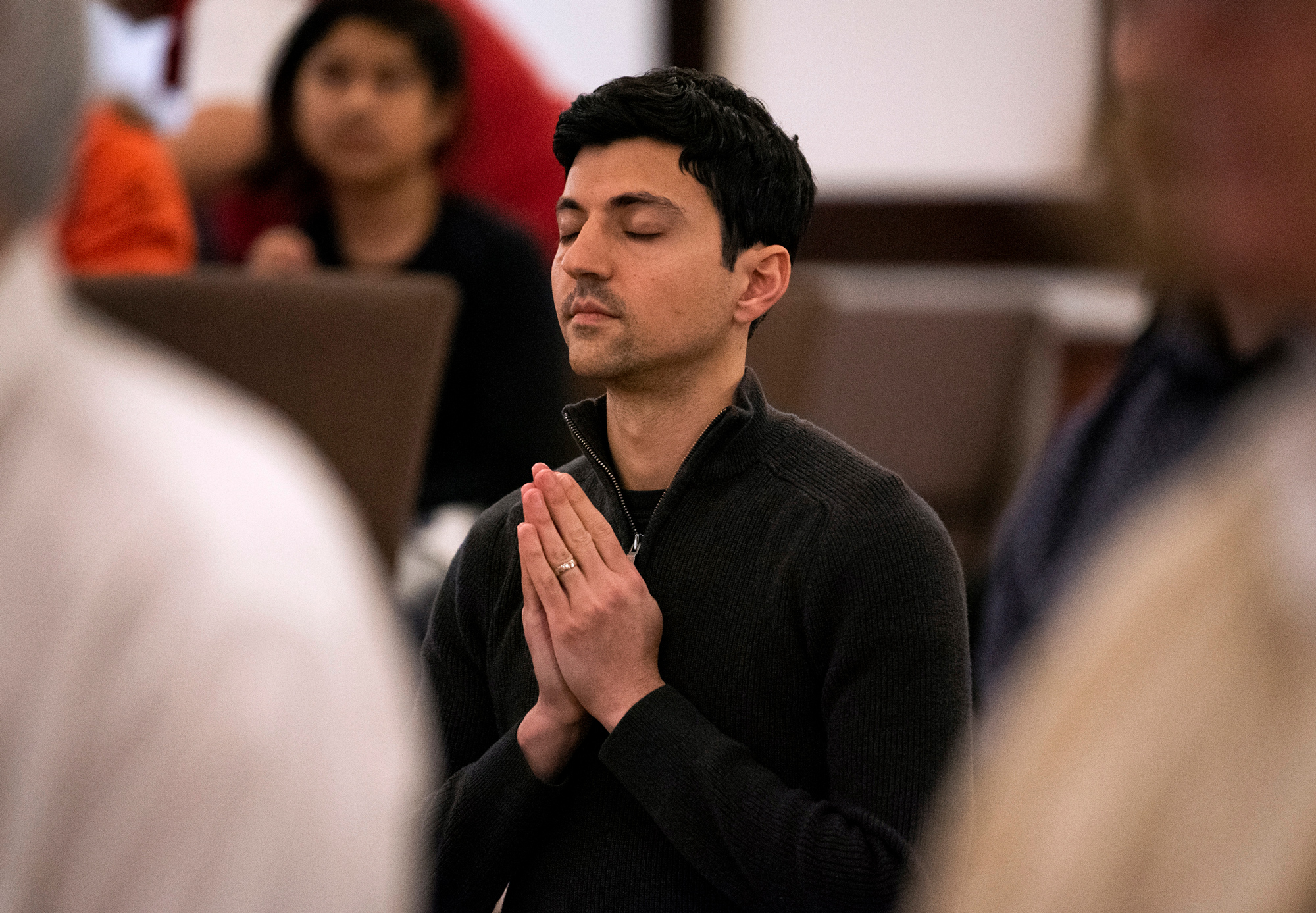

Portland psychotherapist Wes Harris said he got connected to the hermitage through Portland Friends of the Dhamma, the group that helped get the Gorge monastery started.

Harris meditates daily and tries to practice what he preaches, encouraging mindfulness among his clients. Mindfulness has become a buzzword, the concept having been brought to the mainstream and to the attention of the medical community.

“There’s an interesting crossover between Buddhist psychology and secular psychology,” said Harris, 38.

He said he used to visit the monastery in White Salmon monthly, but that got more difficult after having a daughter, now 3.

“What naughty things do the monks do? That was her question of the day,” he said. (Sudanto later answered that monks aren’t supposed to be separated from their robes for more than a night, but that can get difficult if they’re on a long-distance flight and changing time zones.)

Harris recently made the trek to offer food for the monks’ daily meal, which must be eaten before noon. He heated an egg dish and set out kale salad, along with sliced fruit and cheese and food offered by the Montessori school students: sandwiches, muffins, apples and a can of refried beans. When the smorgasbord was ready, Harris picked up each item and offered them to Kassapo.

“Anything we eat has to be formally given to us,” Sudanto explained. “You never eat without acknowledging the generosity of the donors.”

The monks ate in silence, mindfully enjoying what’s been provided.

Visiting the hermitage is a valuable experience, Harris said; it offers a chance to be of service to the monks and to ask questions or get guidance on life’s challenges. It’s why people from the greater Portland-Vancouver area make the 70-mile drive. The monks also visit Portland monthly to lead meditations and teachings.

“If there’s something of concern going on in their life that they’re suffering with, they oftentimes want to talk about it and want to understand what I think, what the Buddha would think, what the right course of action is,” Sudanto said. “I’m not a licensed counselor or family counselor or something like that. And I try to sort of stick to speaking about how the Buddhist teachings might relate to what it is that they’re going through.”

Often, the lay community wants to talk with the monks about issues of aging, illness and death.

“No matter how well off you are, you’re not immune to those tragedies of life. And, even when we’re not in the immediate grip of that, part of us lives under the shadow. And it creates a certain level of emotional, spiritual suffering,” Sudanto said. “People seem to be flourishing and in many dimensions are better off than ever, but there are studies and other forms of evidence that people are not happier, actually.”

It’s true. The 2019 World Happiness Report found that happiness is declining in the United States. For the third year in a row the U.S. dropped in the ranking, and is now the 19th happiest country.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Journey

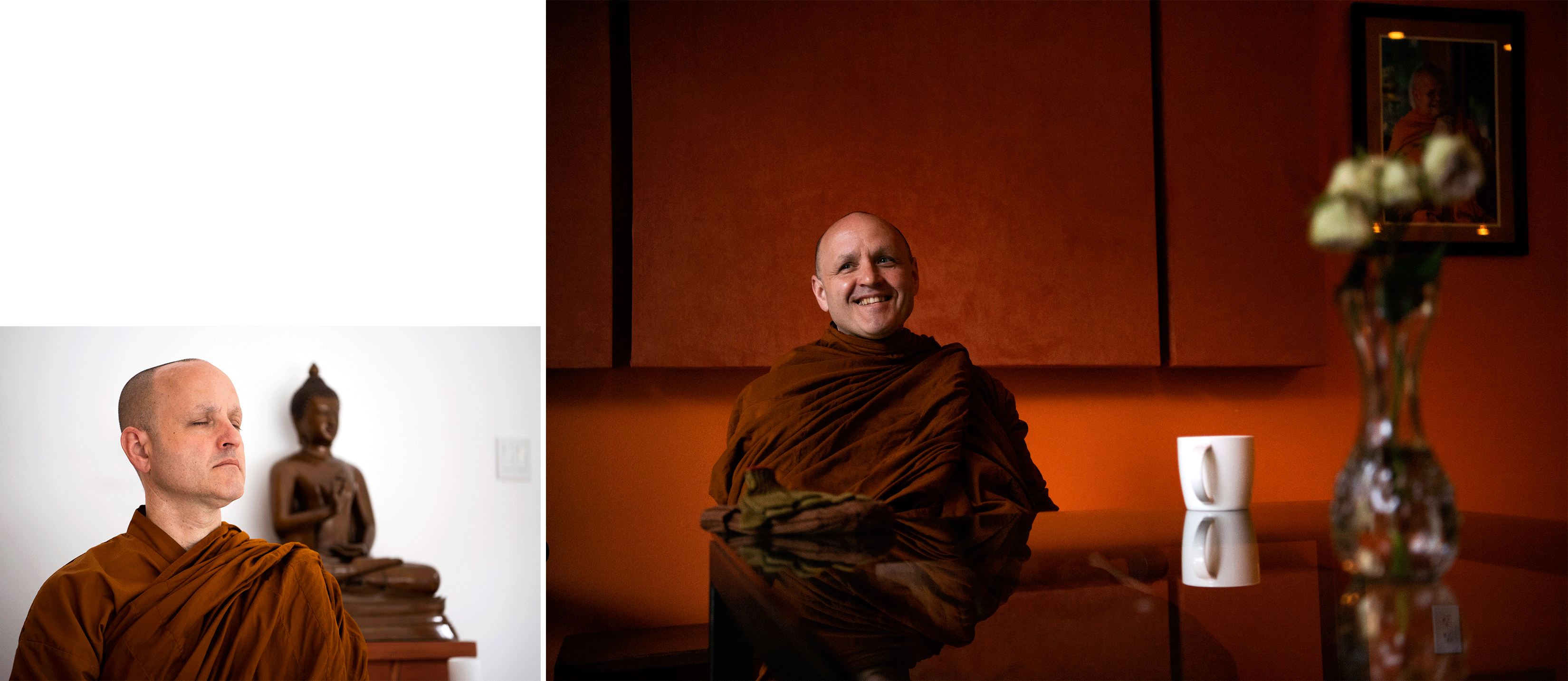

Sudanto sought happiness in his own journey to becoming a Buddhist about 25 years ago. He was born Mark Steel, grew up in Vancouver and attended St. Joseph Catholic School. He delivered newspapers for The Columbian and attended Clark College and the University of Oregon.

“I think I got a D in yoga at the University of Oregon and I was an atrocious meditator,” Sudanto said. “I didn’t think of myself as religious at this time.”

When he left Eugene to study yoga and meditation in Asia, his life had never been better. He had a job, friends, had studied exactly what he wanted to study and had avoided student debt. But something was missing.

“I remember sort of thinking broadly about my life at the time and just thinking ‘I don’t think any one of these things, or even having all these things, will ever kind of address that subtle feeling of lack that always seems to kind of creep into our experience of life,’ ” he said. “Somehow it never feels perfect. It feels good, it feels interesting, it feels exciting, it feels happy in the good times, but that’s different than feeling perfect. Like, when things are perfect you feel like you don’t want any more. You feel content, you feel satisfied.”

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Sudanto ordained at a monastery in Thailand and joined a newly established monastery, Abhayagiri in Redwood Valley, Calif. People in Portland expressed interested in having monks located closer.

Having grown up in Vancouver, Sudanto said he knew at any time of the year it would be difficult to meditate in the forest without getting a wet butt. The coast would be even wetter.

“I was quite keen to focus on finding something out here because of its proximity to Portland, the better weather,” Sudanto said.

White Salmon’s motto is the land where the sun meets the rain.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Home

The hermitage consists of a two-story house surrounded by trees and rocks. The house is used for group meditation and meals. The monks sleep in kudis, or small huts, flanked by wooden walking meditation paths.

There are plans to build more kudis, but the hermitage won’t get much bigger than five monks, Sudanto said. After all, the city supporting them has only about 2,500 residents.

White Salmon is growing, though.

Jean-Marc Lenoir, 50, moved to the area in 2010 for the extreme sports scene; White Salmon boasts easy access to windsurfing, kiteboarding, mountain biking and kayaking. (No, the monks don’t partake, though that hasn’t stopped friends from asking if they would like to give windsurfing a go. “I’m sure I would like it. But there’s just a whole sense of what’s appropriate for a monk to do. I’m pretty sure that’s not appropriate,” Sudanto said.)

A mechanical engineer with Boeing, Lenoir said meditation has brought him more peace, less stress and less anxiety, but it was something he struggled to learn by just reading about it. He finds the monks’ teachings practical and regularly attends Tuesday night meditation at Yoga Samadhi.

“The monks give the studio an authenticity,” said owner Kathy Kacena, 69. “There are people who are just drawn to that.”

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

She’s seen new, younger faces show up at her studio. She even came across people debating between relocating to White Salmon or Bend, Ore., and choosing the former for its closeness to the monastery.

“I do know it’s influenced my spiritual life beyond what I can even appreciate,” she said. “Having Buddhist monks living in your town and teaching is so rare. It’s just mind-boggling, really.”

Sudanto said he’s only had a few negative interactions in White Salmon. A couple of high school kids flipped him off one morning.

“They both had huge smiles on their faces and they were laughing. And I just started laughing, too,” Sudanto said.

When asked what he thinks the monks contribute to the community, Sudanto replied that they demonstrate there are options other than the hustle and bustle of mainstream cultural life.

“Sometimes we’re representative of that, and maybe a representative of peace and serenity.

“I think there are so few people who are dressed and recognizable as somebody who’s made a lifetime commitment to spiritual practice,” he added.

The monks don’t proselytize. There are clear rules against engaging in missionary practices. They’re not in White Salmon to spread the word of the Buddha.

“We’re only allowed to talk and teach to people who have asked for it, who’ve given a clear sign, if not an explicit sign ‘Please, can you tell me about Buddhism?’ ” Sudanto said.

Evidently, there are enough people in White Salmon and beyond who have given Pacific Hermitage that sign.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Meet the monks of Pacific Hermitage

• Meditate with the monks Tuesdays at Yoga Samadhi, 177 W. Jewett Blvd., White Salmon: 5:15 to 6:15 p.m. for experienced meditators; 6:30 to 8 p.m. for all levels (includes Dhamma talk).

• The monks visit Portland Friends of the Dhamma, 1404 S.E. 25th Ave., Portland, third Fridays and Saturdays, April through November: 5:30 p.m. Friday is tea/questions and 7 p.m. Friday meditation and Dhamma talk; 10:30 a.m. Saturday is their alms round.

• Garden parties are held on the first Saturday of every month between April and November at the hermitage, 65 Barnedt Road, White Salmon: 11 a.m. potluck, 1 to 3 p.m. yard work and projects.

• More information at pacifichermitage.org

Ask a monk

How does Theravada Buddhism differ from other forms of Buddhism?

Theravada Buddhism is most prevalent in South and Southeast Asia. It is rooted in the earliest and most complete collection of the teachings of the historical Buddha. It places those teachings at the center of how followers understand Buddhism and how they apply it and practice Buddhism as a lived religion.

How many forms of Zen Buddhism are there?

It’s hard to count because they’ve come and gone and evolved. The more nuanced answer would be “who knows?” There are two main Zen schools in Japan. Zen Buddhism is a Japanese adoption of the Chinese Chan tradition; the core practice of Chan is zazen, which is just sitting.

Are there nuns (female monks) at Pacific Hermitage in White Salmon?

No, Pacific Hermitage is a satellite of Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery in Redwood Valley, Calif., where 15 to 20 monks live at any given time. It’s intended for monks from that monastery to live in a smaller, simpler environment for a period of time. In England, nuns and monks live in a dual community. There is a recent movement to revive more ancient forms of bhikkhunis, or fully ordained female monastics.

— Ajahn Sudanto