Efforts underway, but more money needed to make real inroads, experts say

Monica Stonier will never forget the day she learned why diversity among teachers matters.

About 20 years ago, as a new teacher at Evergreen Public Schools, a kindergartner approached her and looked her over.

“You’re brown, just like me,” Stonier recalls the little girl saying. Stonier is Latina and also has Japanese heritage.

Stonier was stunned. She spent the whole day looking around, noticing her fellow teachers — and how few of them are people of color.

“This cute little babe just stated this thing that was so different for her in such plain terms,” she said. “It wasn’t front-of-mind for me until I recognized how important it was to that little girl.”

Enlarge

(Amanda Cowan/The Columbian)

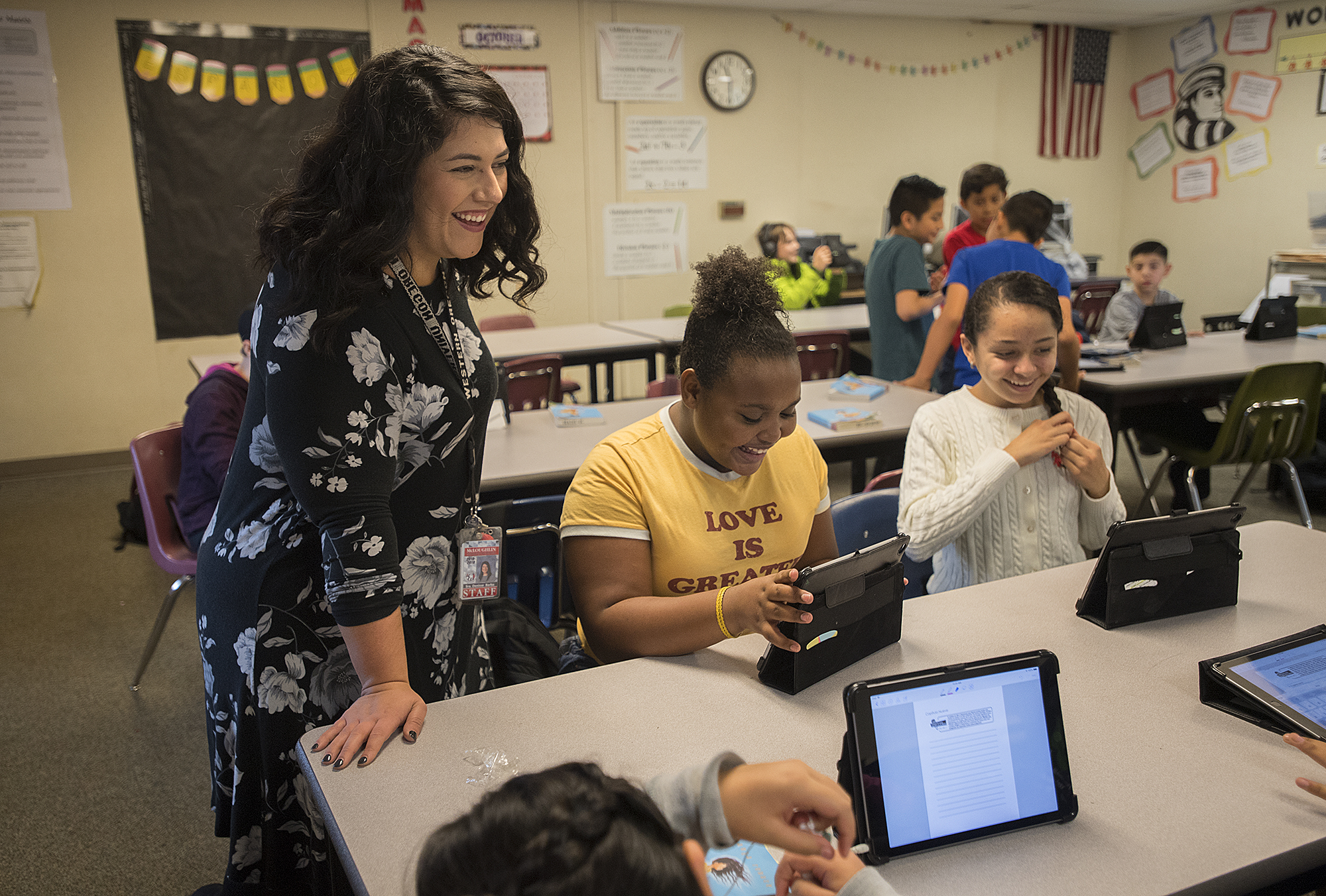

In Clark County, the disparities between the number teachers of color and students of color are steep. Our teaching body looks much the same as it has for years, with only 7.9 percent of the county’s 4,750 teachers identifying as people of color, up from 7.2 percent in the 2012-2013 school year. Of about 550 teachers added locally in the past six years, about 70 identify as people of color.

By contrast, 33.7 percent of Clark County’s 80,323 students identified as a race other than white in the 2017-2018 school year.

But there’s some potential that Washington is poised to increase teacher diversity. In recent years, the state has expanded its Alternative Routes to Teacher Certification, nontraditional teacher training programs targeted at paraeducators or people with bachelor’s degrees pursuing new careers. Three of those programs are based in Southwest Washington.

Organizers say, however, that those programs remain underfunded, and Stonier, who is now a Democratic state legislator representing Vancouver, worries her peers in Olympia may not see teacher diversity as a priority.

Still, because these programs tend to trend more diverse than traditional teacher training pathways, area districts hope the population of teachers of color will grow.

“If (teachers of color) aren’t available and they aren’t out there looking, that’s a barrier,” said Gail Spolar, spokeswoman for Evergreen Public Schools. “That’s why we have to get creative with some of these pipeline programs.”

Enlarge

(Amanda Cowan/The Columbian)

Chipping away at the issue

Alternative teacher certification programs, sometimes called “Grow Your Own” programs, are typically shorter and less costly than traditional routes, while allowing people to pursue their certification without uprooting their lives. In this region, about 60 students are pursuing new teaching certifications through an alternative route, an estimated 17 of whom are people of color.

That echoes state trends in alternative route programs, which tend to be more diverse than the teaching body as a whole. About a quarter of teaching candidates enrolled in alternative route programs across the state are people of color, according to the Professional Educator Standards Board. Meanwhile, 11 percent of teachers in the field are people of color.

Enlarge

(Amanda Cowan/The Columbian)

Amaya Garcia, the deputy director of English learner education for New America, a public policy think tank that receives steady funding from Google and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, pointed to these programs as an example of the state being ahead of the curve on diversifying its teacher workforce.

“It’s an exciting development,” Garcia said. “Washington’s taken a lead on it in attempts to diversify the workforce.”

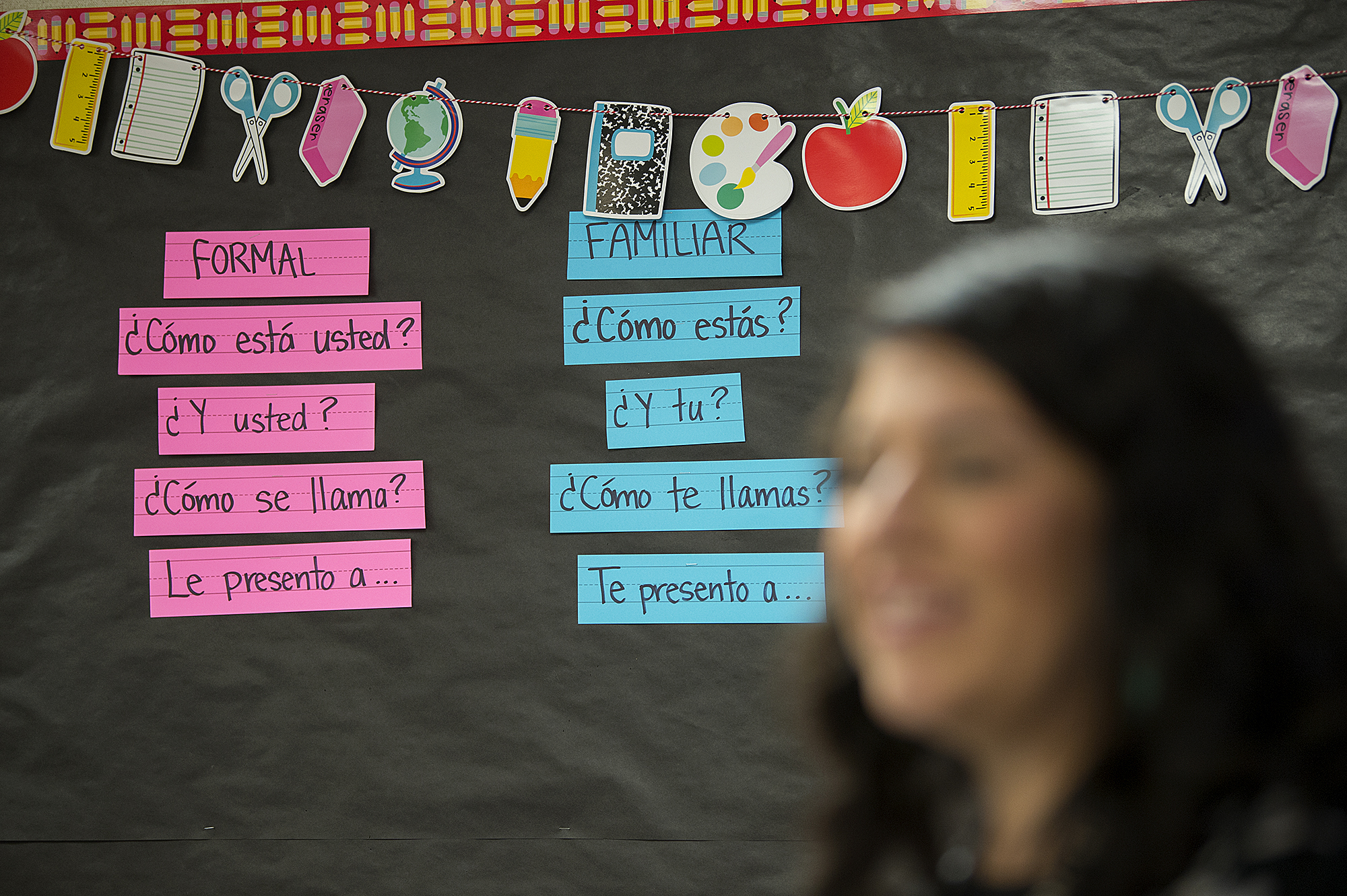

At Washington State University Vancouver, a cohort of predominantly Latino and Hispanic paraeducators from Evergreen Public Schools are pursuing their teaching degrees.

Enlarge

(Nathan Howard/The Columbian)

The university recently won a five-year, $2.2 million grant to provide bilingual paraprofessionals in Vancouver and the Tri-Cities with scholarships to complete their bachelor’s degrees in education with English-learners endorsements. The program is called the Equity for Language Learners-Improving Practices and Acquisition of Culturally Responsive Teaching, or ELL-IMPACT. Those teachers are expected to enter classrooms next fall.

That’s key for the Evergreen district, where 22.7 percent of the district’s 25,704 students were Latino or Hispanic last school year but only 2.9 percent of its 1,534 teachers were. For every Latino teacher in the district, there are about 130 Latino students. For every white teacher, there are about 11 white students.

Students of color overall made up 42.4 percent of Evergreen’s enrollment. Teachers of color, meanwhile, made up 8.1 percent of the teaching staff.

Neighboring Vancouver Public Schools has slightly more representation, with 26.6 percent of the district’s 23,744 students identifying as Latino or Hispanic compared with 4.4 of its teachers. For every Latino teacher in Vancouver there are 105 Latino students, compared with 11 white students for every white teacher.

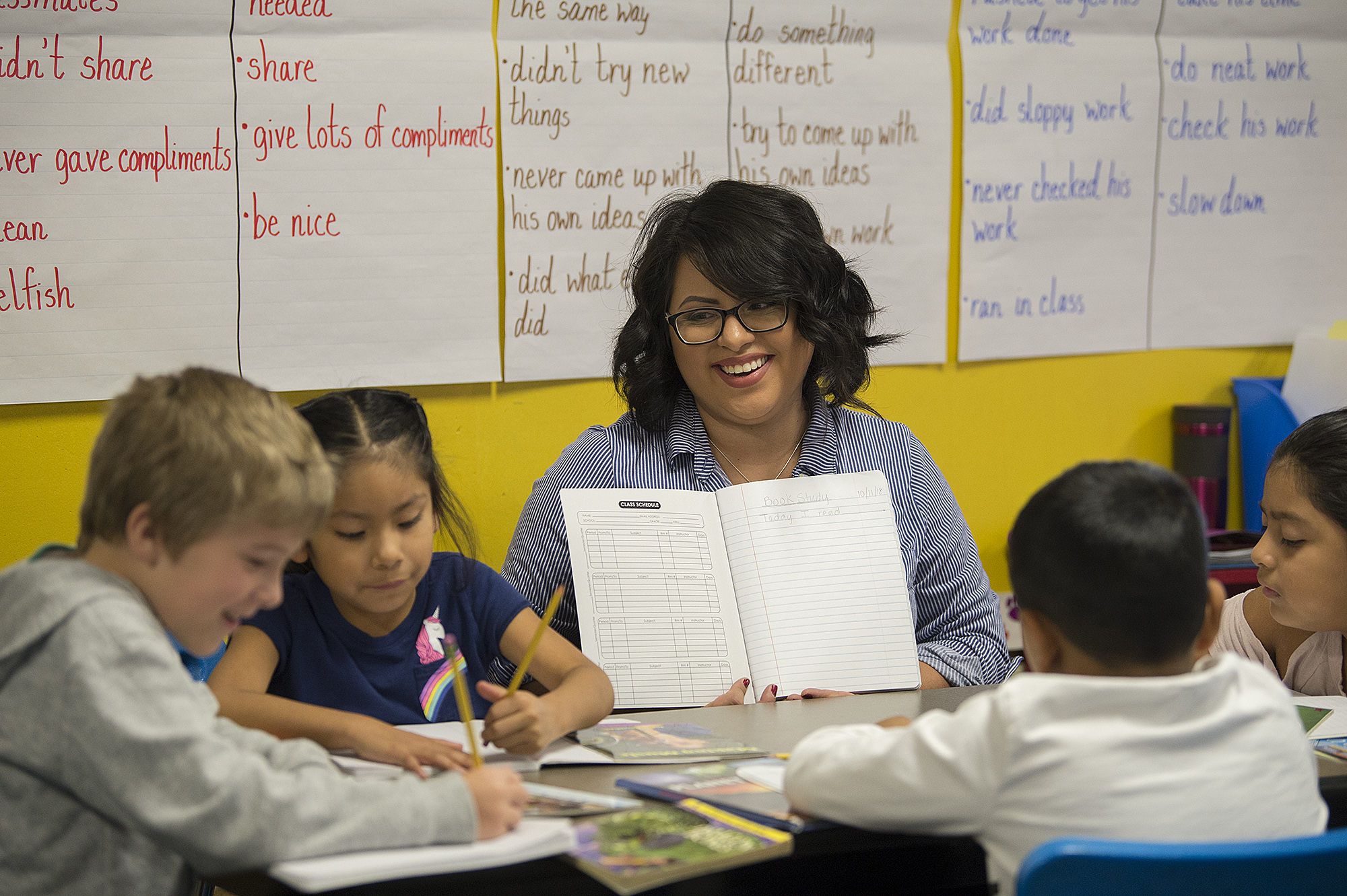

Gisela Ernst-Slavit, a WSU Vancouver education professor, is the lead instructor on the ELL-IMPACT program. She touted her students’ intimate knowledge of the school communities, their existing relationships with families and their familiarity with district bureaucracies.

“They know the system very well, so they can function as advocates for the students they are teaching,” she said.

Enlarge

(Nathan Howard/The Columbian)

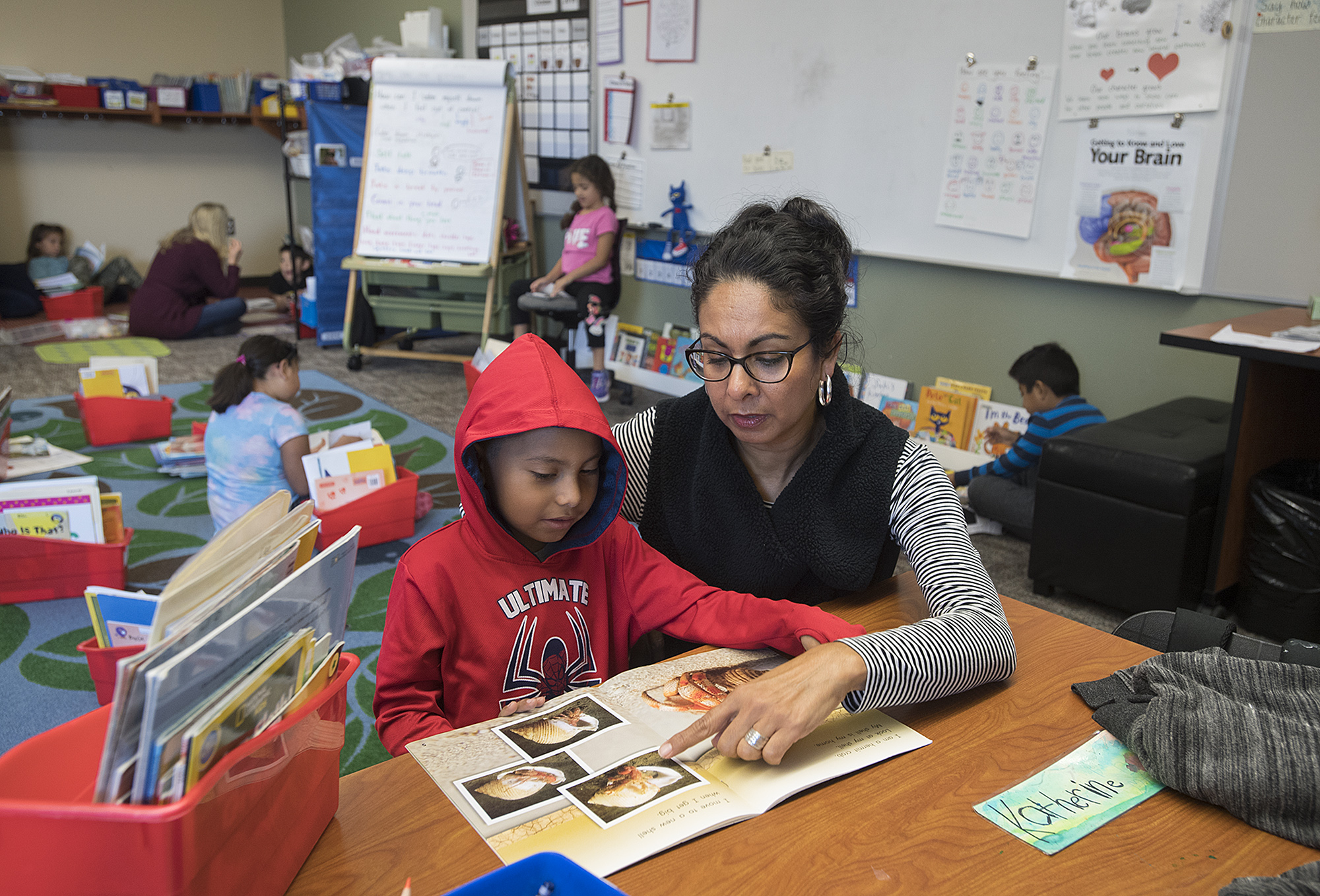

Melissa Sifuentes Phillips, an English-language learning paraeducator, is a member of that class. She’s a paraeducator at Crestline Elementary School, where she’s helped establish a network of Latino parent volunteers. Her passion for those families is what drew her to teaching, she said.

“I want to be an ambassador for students of color,” she said. “Our classrooms are way diverse, but we don’t see that in their teachers.”

Sifuentes Phillips is already seeing the impact those connections have on her students. She recalled a recent conversation in Spanish with a little girl in her classroom. When the student walked away, she heard the smiling girl tell her friends, “she talks like me.”

“They need to feel like they belong,” Sifuentes Phillips said of her students and their families.

Underfunding

But alternative certification programs remain chronically underfunded, says Alexandra Manuel, executive director of PESB. The Legislature budgeted about $1.8 million toward a block grant to fund “Grow Your Own” programs, but Manuel said the agency plans to request $5.2 million to expand them.

“Providers are interested in this group, but we have to be able to provide funding and incentives to make this stick,” she said.

Take Vancouver-based Educational Service District 112, for example. Last year it became the first non-college to offer an alternative pathways program. ESD-U offers certification training for people who already have their bachelor’s degrees, or additional certification for teachers looking to teach a different subject.

But the program is funded through tuition dollars or school district investments, and has not received funding from PESB to provide scholarships to new teaching candidates.

Enlarge

(Amanda Cowan/The Columbian)

That’s limited the district’s ability to recruit diverse candidates, said Mike Esping, director of educator effectiveness and early career development for ESD 112.

Currently, five of the 25 candidates pursuing new teaching certifications identify as people of color. That means the ESD-U program is still more diverse than the county’s existing teaching staff, but Esping said the program’s not been successful in recruiting people of color.

“I don’t think in any way we’re making gains,” he said.

Stonier was among those who advocated for that funding to improve access to the program during the last legislative session. The bill would have provided $8,000 in scholarships to 30 ESD-U candidates during the 2018-2019 school year, but it died in committee.

Stonier hopes her peers will see the need to invest in programs like ESD 112’s as a platform for diversifying the workforce.

“It certainly isn’t true everywhere, but access to higher education and advanced degrees in communities, especially if they’re communities of color, just often aren’t as attainable,” Stonier said.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

Changing the face of educators

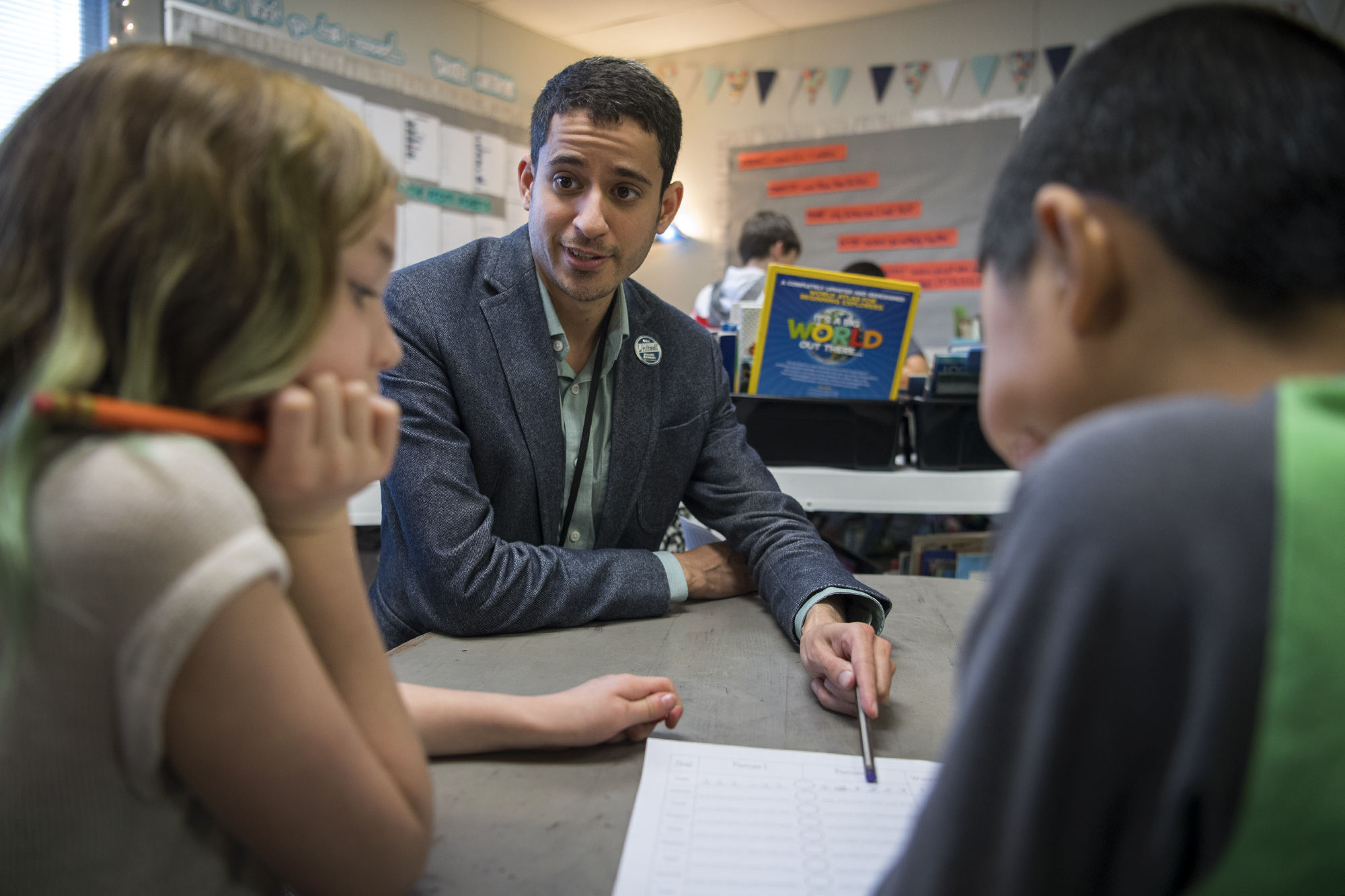

Adam Aguilera is among the few Latino teachers in the Evergreen school district, and a supporter of the “Grow Your Own” model. He also helps lead cultural responsiveness training for the district — meaning, he teaches teachers to respect all students’ backgrounds and identities, racial or otherwise.

“It’s basically sort of that subconscious bias that you may have against a student,” he said. “A well-meaning educator can actually make a student uncomfortable.”

Marla Morton is a speech language pathologist at Cascade Middle School who co-leads training with Aguilera. Though it’s critical that school employees have awareness of their own biases, that can only go so far. Morton said districts must also invest in recruitment and hiring of diverse teachers so students have role models who reflect their own backgrounds.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

“Our population is changing and our students need to see people who look like them,” Morton said.

Aguilera, an English teacher on special assignment this year, said he encourages his students to “speak their truth” in his classroom. He believes that, combined with his own heritage, is why his students of color, girls and LGBTQ students feel safe in his classroom.

“I really emphasize that we have a safe space where they’re respected, where their views and their voice is important,” he said.

Aguilera is optimistic that alternative route programs, like Evergreen’s, will create a class of teachers who reflect their students’ communities. He also said these programs eliminate barriers for people of color to access middle-class jobs and higher education.

“In a generation’s time, that would change the face of our educators,” he said.

Katie Gillespie: 360-735-4517; katie.gillespie@columbian.com; twitter.com/newsladykatie