Teaching corps doesn’t reflect increasingly diverse student body

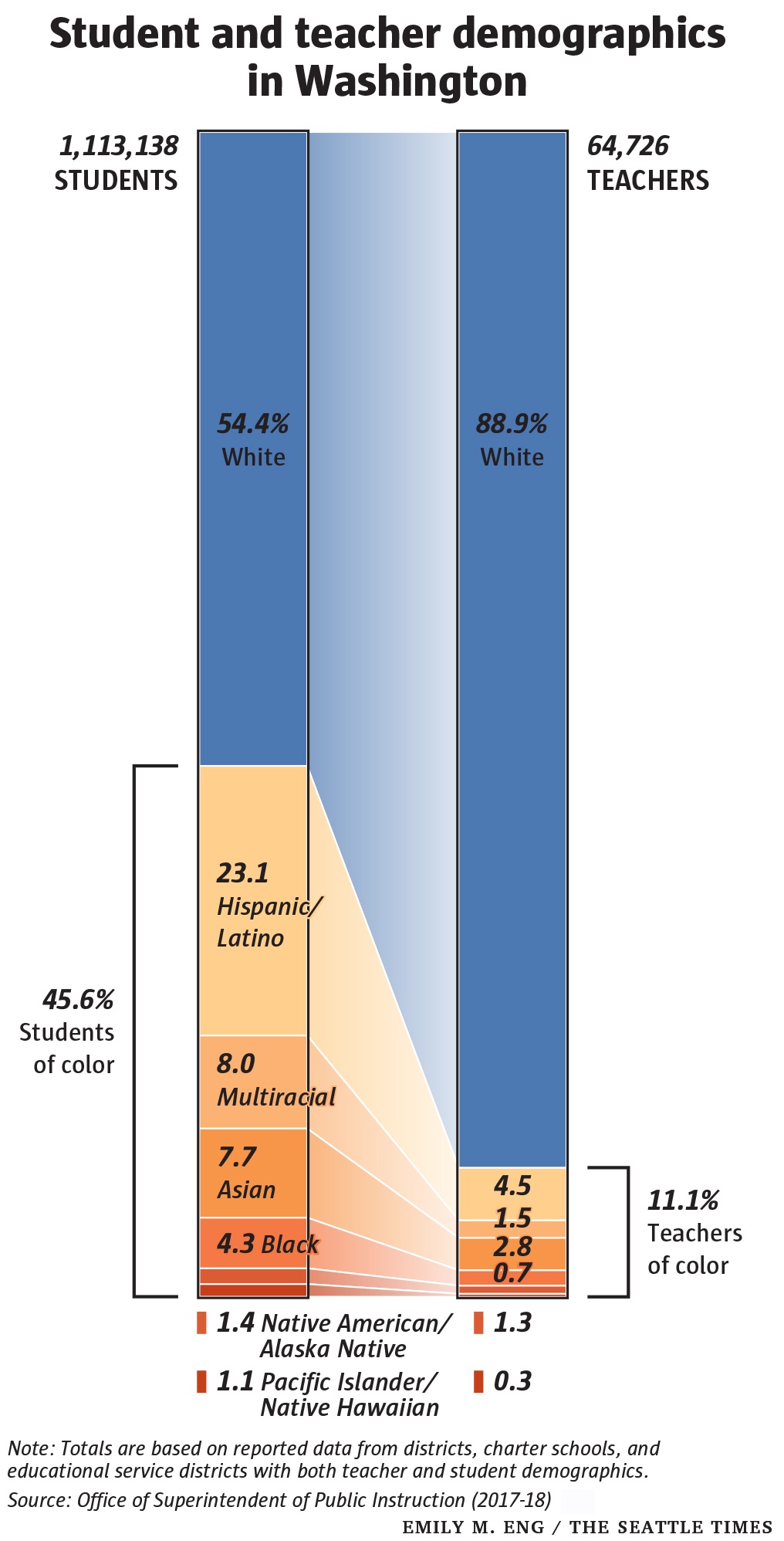

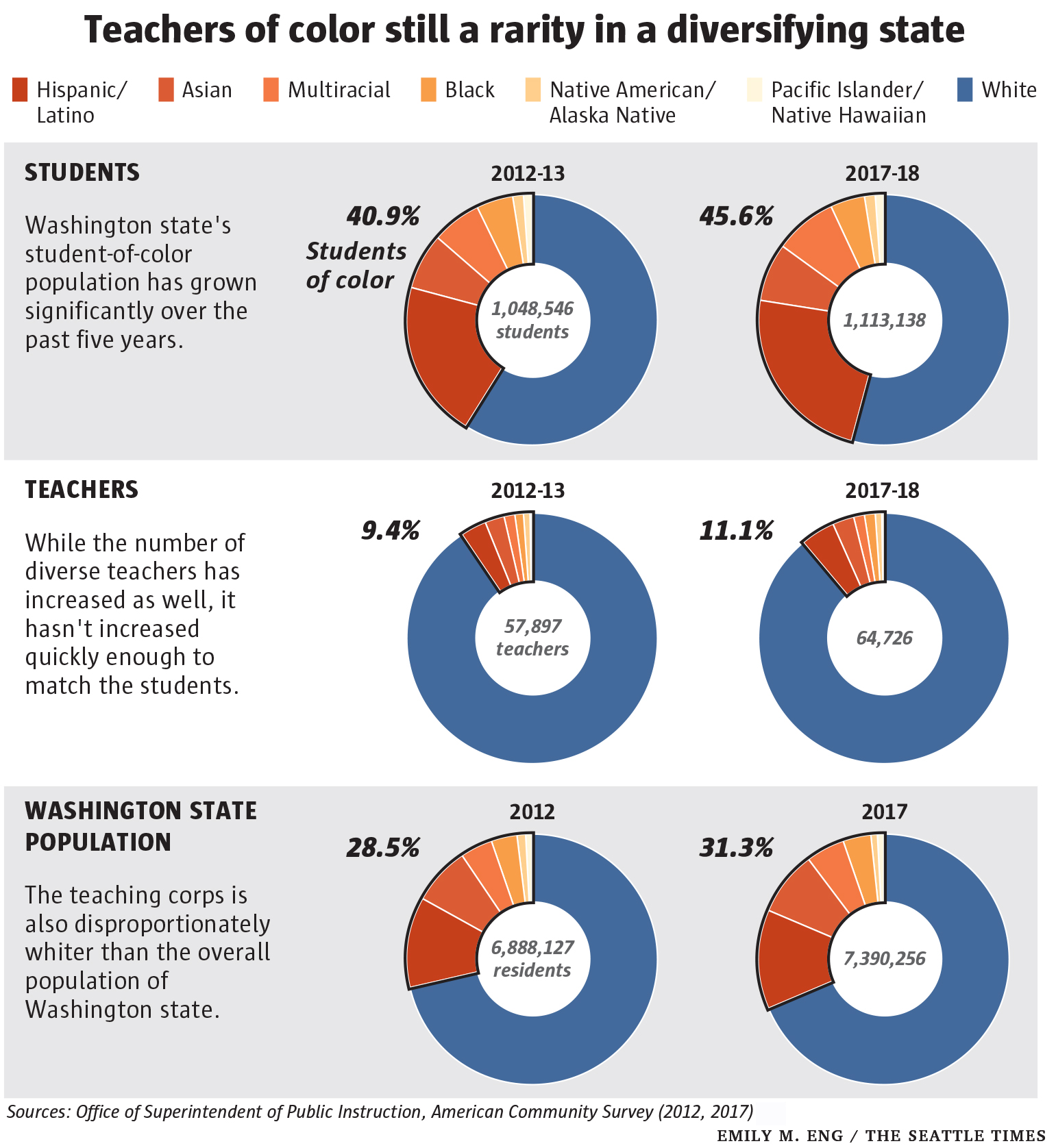

As students in Washington classrooms have become more diverse, the teachers who stand before them have remained almost always white.

It’s a chasm that has remained stubbornly wide for decades, worsened by barriers to higher education, teacher credential tests and limited funding to diversify teacher training programs.

A joint analysis by The Seattle Times and The Columbian newspapers found that even though the number of teachers of color is growing at a faster rate than that of white teachers, there are still few of them in classrooms. The newspapers looked at all 313 school districts, charter schools and educational service districts that sent teacher and student demographic information to the state. Last school year, nearly a quarter of Washington’s school districts had no teachers of color.

To Washington’s students, that lack of diversity matters — researchers say it can have lasting impacts on high-school completion, discipline rates and test scores for students of color.

Students like 17-year-old Lindsey Luis, a senior at Fort Vancouver High School, can spend nearly the entirety of their time in school without having a single teacher who looks like them or shares their background.

“There’s nothing like that one person you can speak Spanish with,” said Lindsey, who is Latina. “I’ve never had someone to relate to on a personal level.”

Achieving parity

Over the last five years, Washington’s schools have seen an 18 percent increase in the number of students of color — and a 2 percent decrease of white students. The growth of teachers of color, an increase of 32 percent, also outpaced the number of new white teachers, which was about 10 percent.

Still, three out of every four teachers the state has gained in the past six years were white.

For students who identified as Latino or Hispanic, the state’s second-largest demographic group, the difference is particularly stark. For every 88 Hispanic/Latino students last school year, there was only one Hispanic/Latino teacher.

By contrast, there is one white teacher for every 11 white students, on average.

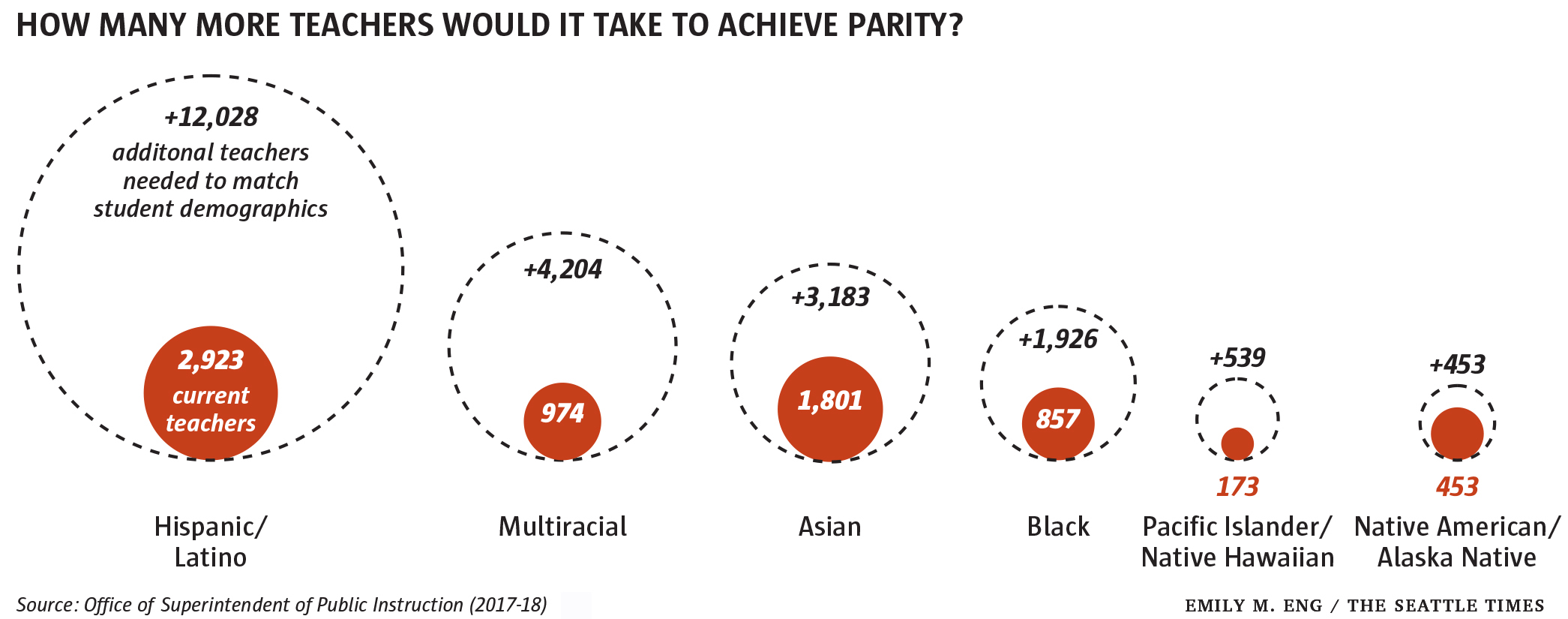

To fully represent today’s student body, about 29,500 of Washington’s 64,700 teachers would have to be people of color. That’s about 22,300 more people of color than those who currently teach here. Closing those disparities would require hiring:

• 12,028 more Latino/Hispanic teachers

• 4,204 more multiracial teachers

• 3,183 more Asian teachers

• 1,926 more black teachers

• 539 more Pacific Islander/Hawaiian Native teachers

• 453 more American Indian/Native Alaskan teachers.

If the number and racial makeup of students and teachers in Washington change at the same rate as they are now, it will be more than a century before the state reaches parity.

To get there, a lot needs to happen, said Chris Reykdal, Washington’s top education official. “We have to diversify our pathways,” he said. “If it’s not an environment they can be successful in, then it’s really exacerbating the pipeline.”

Scoring representation

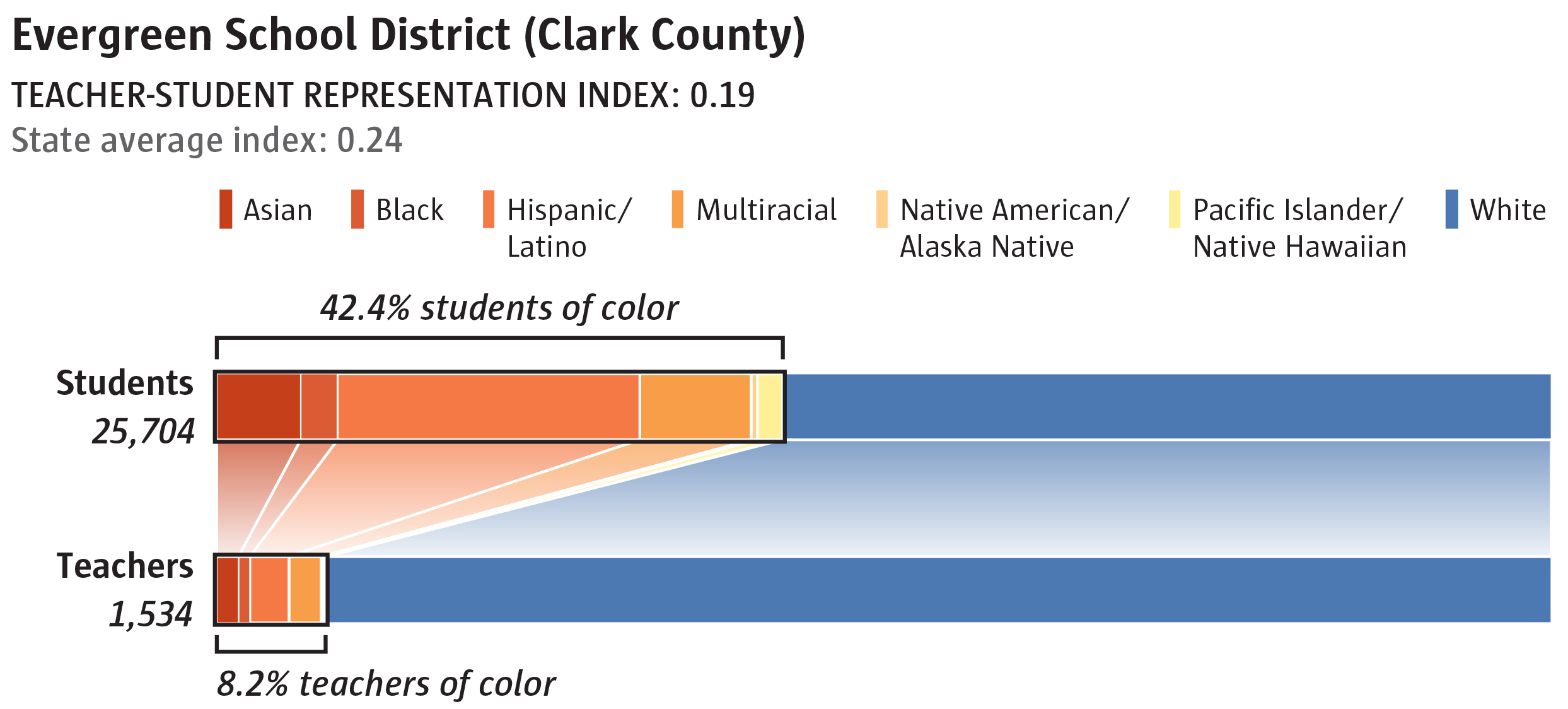

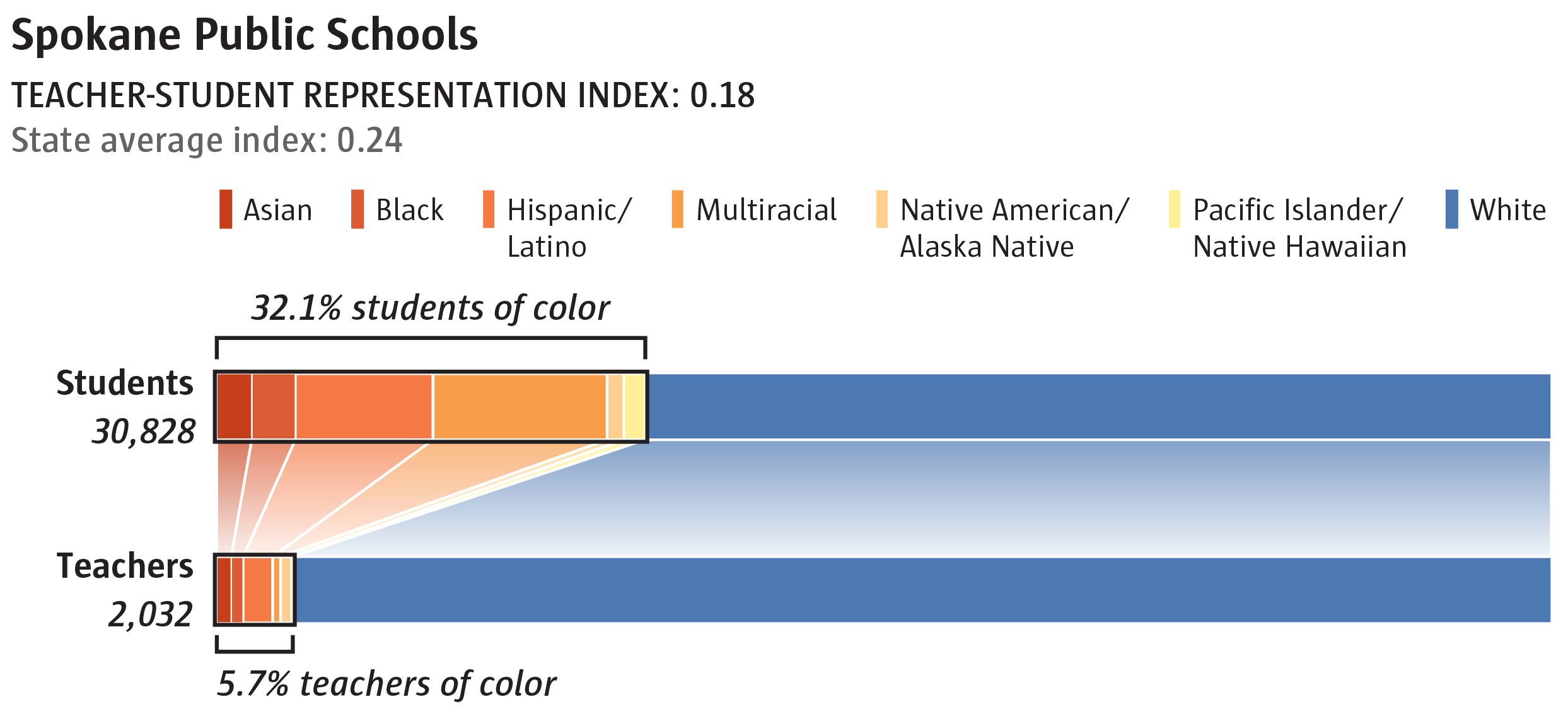

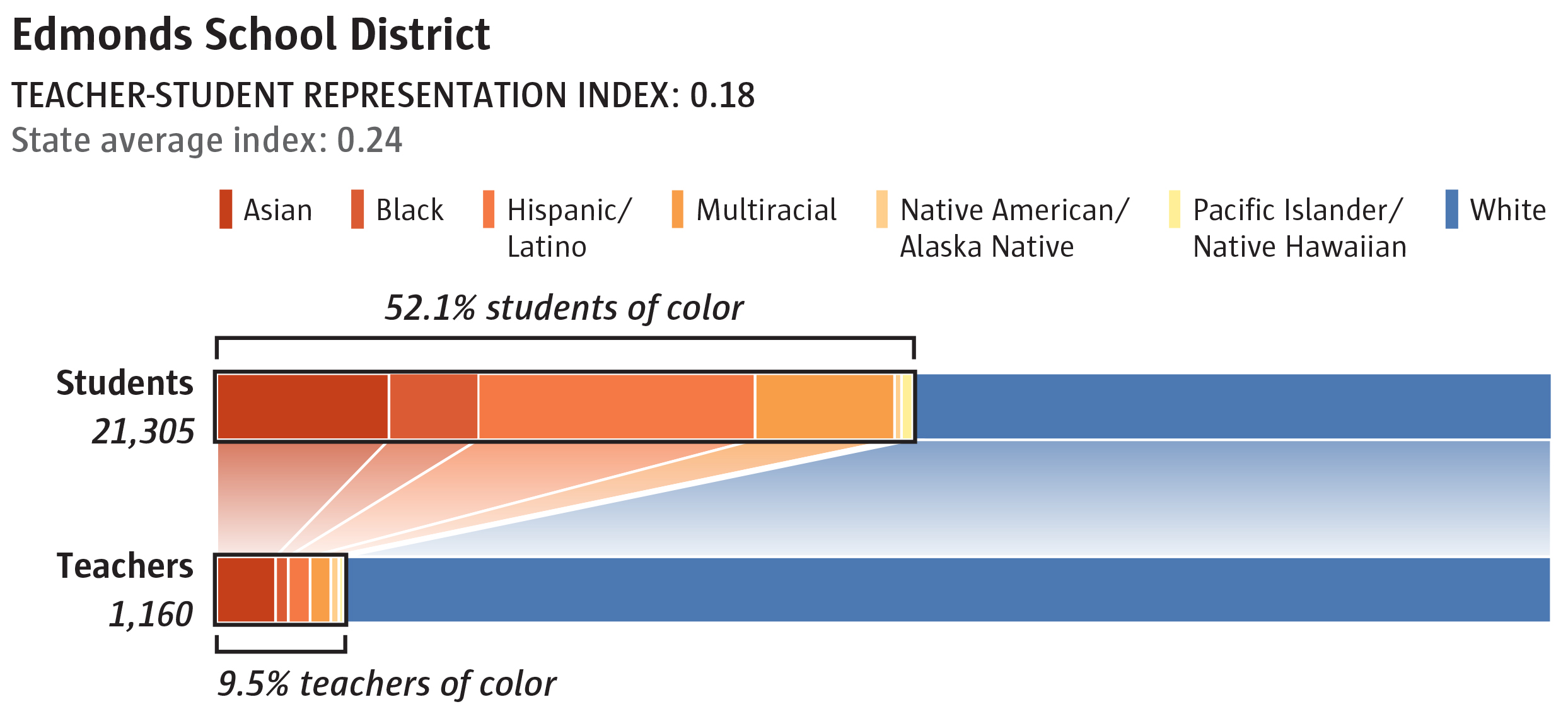

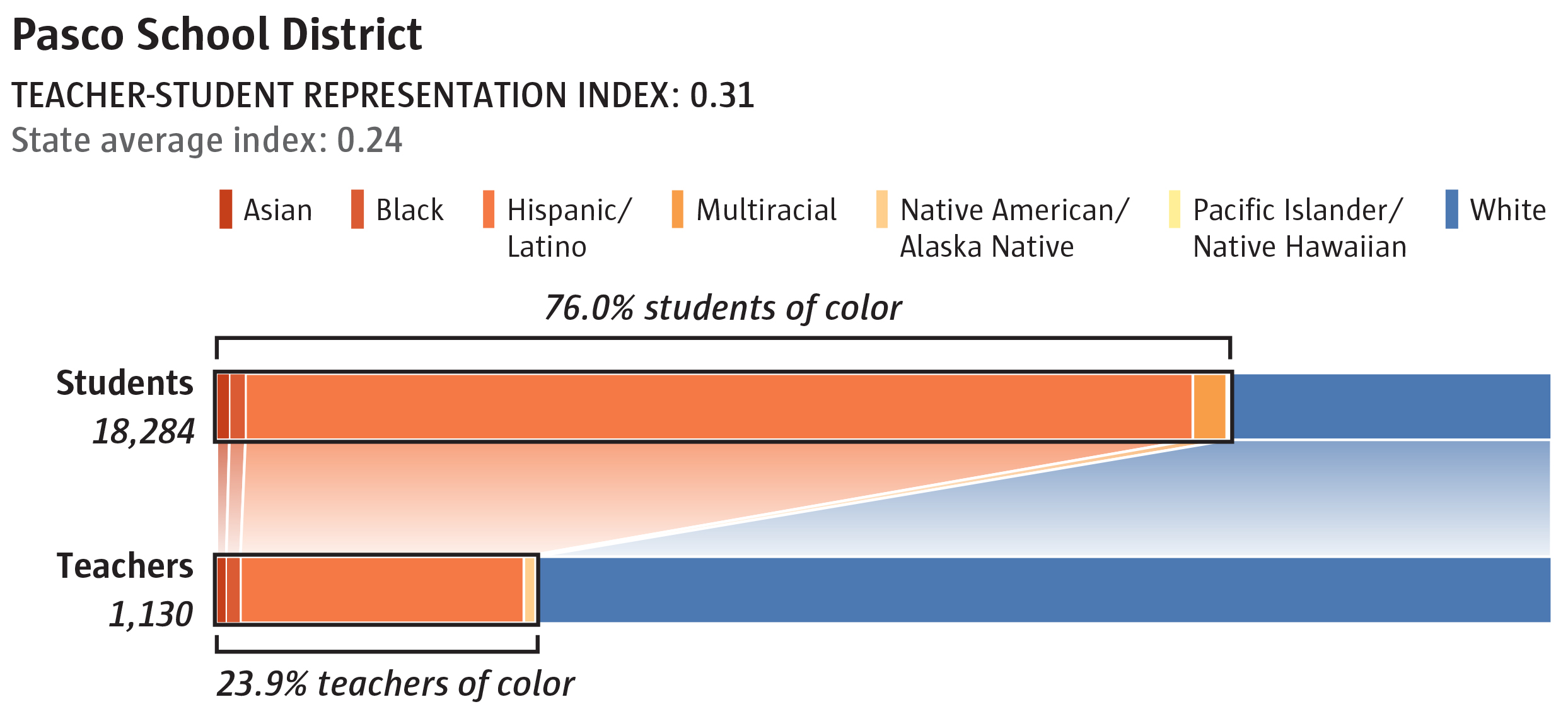

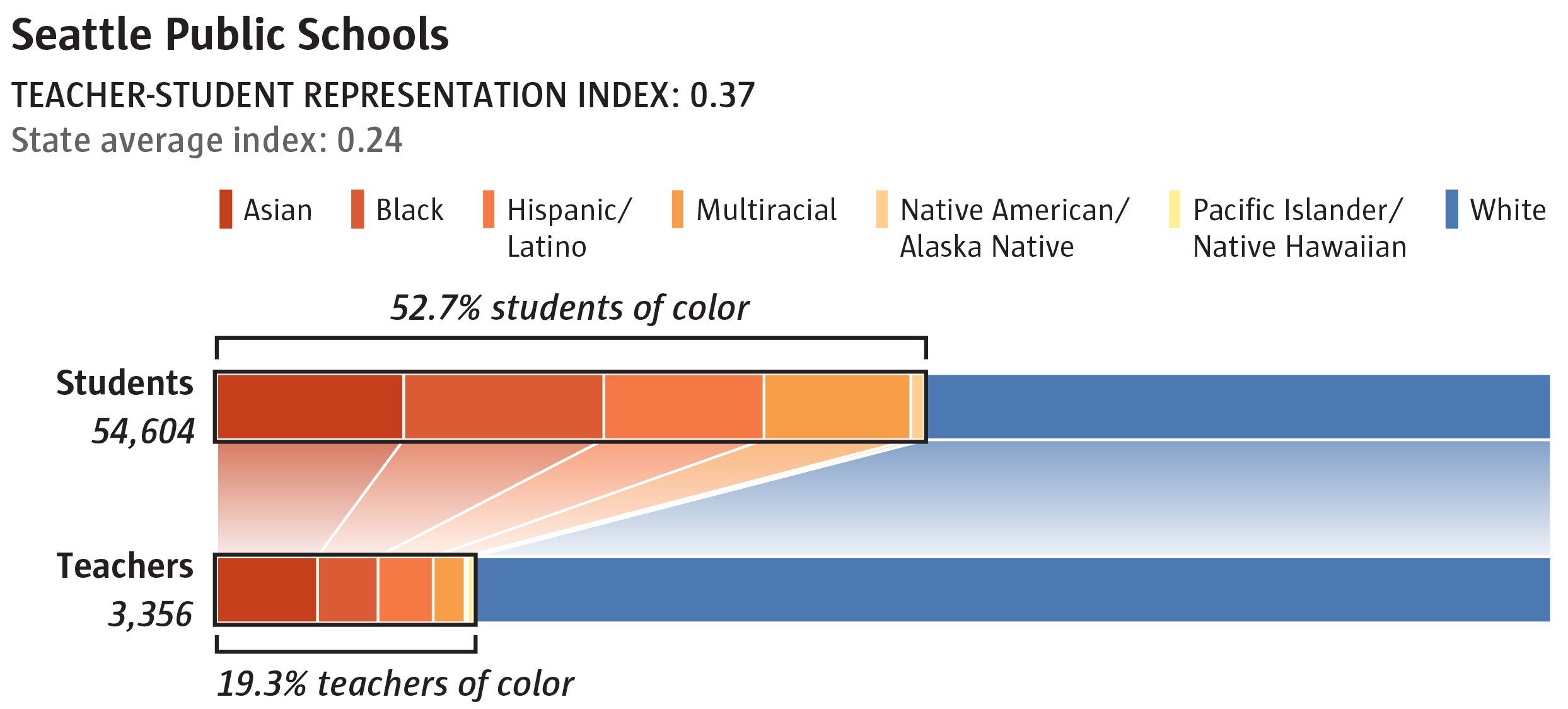

The two newspapers developed a ratio to score districts based on how closely their teaching staffs represent the racial demographics of their students. The higher a district’s score, the more representative its teaching staff is of its students. A score of one means exact representation.

Across the state, white students and teachers had the highest average index, coming in at 1.6, indicating a higher percentage of white teachers than white students. For Latino and Hispanic students, meanwhile, the average ratio was 0.2.

The accompanying map shows how districts fared under the calculation, which divides the percentage of teachers of color by the percentage of students of color.

Luis has her first and only teacher of color — her Spanish teacher, whom she said is Cuban — at Fort Vancouver High School this year. State data from last year shows about 10 percent of the 79 teachers there identified with a race other than white — while students of color made up about 62 percent of enrollment.

“There are those teachers who do try and try their hardest, but there’s never been one who wouldn’t have to try,” the 17-year-old said.

The frustrations of students like Luis are backed by a growing body of research suggesting greater teacher diversity can improve outcomes for students of color.

There are many theories as to why. Among them: Teachers of color may be more likely to set higher expectations for students of color, as a paper published by the Economics of Education Review found.

A 2017 study of more than 100,000 black students in North Carolina found that low-income boys who had at least one black teacher in grades three to five were almost 40 percent less likely to drop out of high school and had a stronger interest in attending college.

Dan Goldhaber, director of the University of Washington’s Center for Education Data and Research, has studied the demographic mismatch of students and teachers in Washington, but he and his colleagues haven’t tried to research the impacts on students. He suspects it would be difficult because of the pool of diverse teachers here is small.

The absence of representation in classrooms could create cyclical recruitment challenges. Gisela Ernst-Slavit, a professor of education and English-language learning at Washington State University Vancouver, said it could engender the sense that school is not a space for students of color, and ultimately discourage them from pursuing careers in education themselves.

Ernst-Slavit said, “When students only see janitors and cooks in the school, but they don’t see teachers or principals who look like them, that is a problem.”

Hurdles start early

There isn’t a single state where the teacher workforce perfectly mirrors its student body. Washington falls in the middle of the pack.

Despite efforts to address the problem, barriers that could hinder aspiring teachers of color begin to mount from the time they graduate from high school.

Take, for example, access to higher education in the first place. The costs of college and poor academic preparation in earlier years have kept students of color from entering Washington’s colleges and universities, according to a report from the Washington Student Achievement Council. That contributes to keeping most university-based teacher training programs predominantly white.

When a student of color makes it to higher education, there is yet another obstacle.

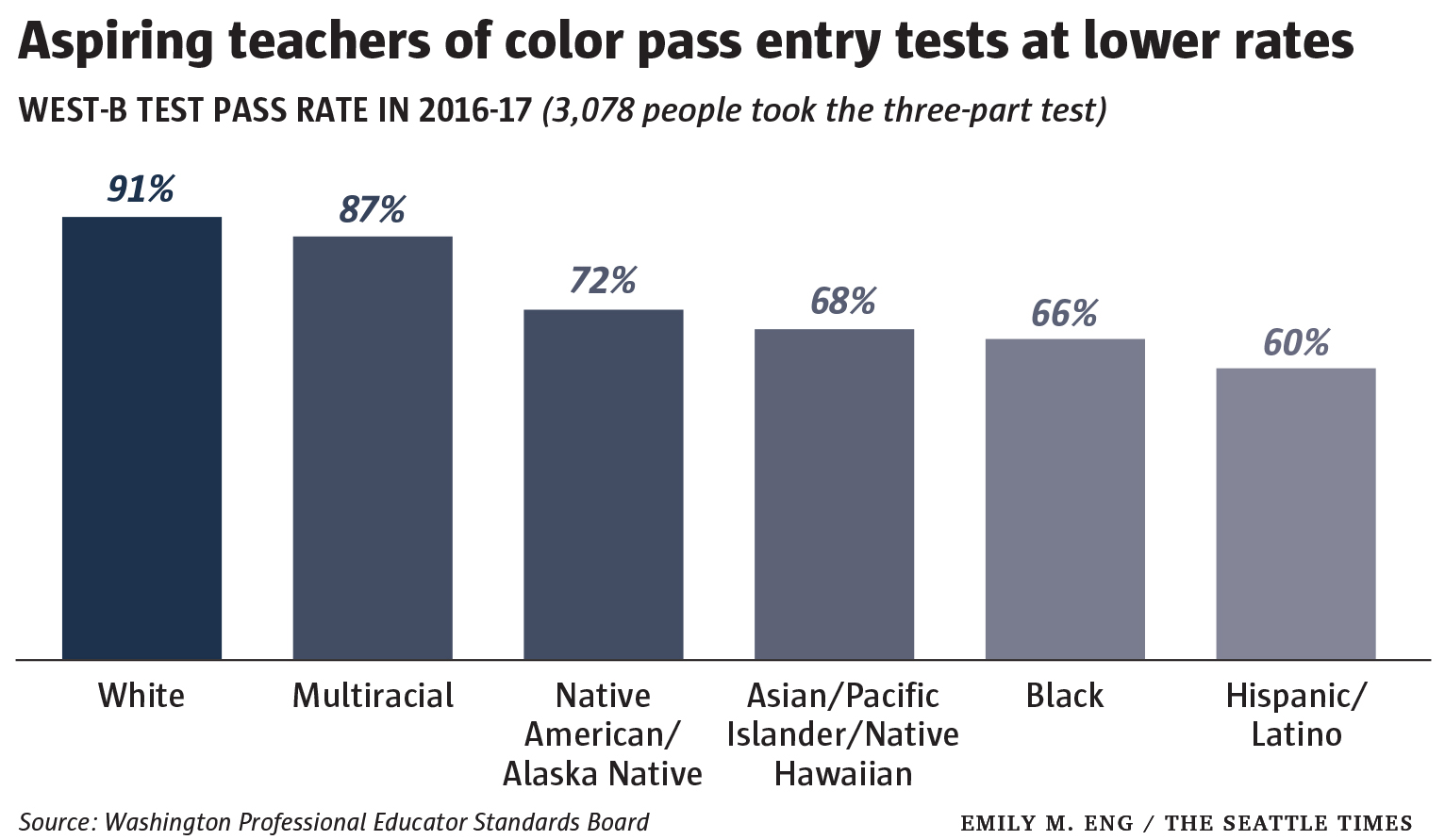

People of color fail the WEST-B — a three-part, mandatory test required for teacher preparation program applicants — at greater rates than their white peers, according to the state’s Professional Educator Standards Board.

While candidates can attempt the test multiple times — and many do so successfully — each test session can cost up to $225, creating yet another potential barrier.

Similar to concerns about the SAT, the tests may carry an “inherent cultural and linguistic bias,” especially for bilingual candidates, the PESB suggested in a recent report. And there are questions as to how well the test predicts classroom success. The board is asking the Legislature to eliminate the requirement that teacher preparation program applicants must reach a certain score for admission. The group is also asking for more funding for so-called “grow your own” programs, alternatives to the traditional certification route that often produce more diverse teachers.

Can Washington turn the tide? Stay tuned for stories Monday and Wednesday on how districts in Southwest Washington and Puget Sound are trying to chip away at the problem.

Katie Gillespie: 360-735-4517; katie.gillespie@columbian.com; twitter.com/newsladykatie

Dahlia Bazzaz: 206-464-8522; dbazzaz@seattletimes.com; twitter.com/dahliabazzaz

This story was produced in partnership with the Education Lab, a Seattle Times project that spotlights promising approaches to persistent challenges in public education. It is produced in partnership with the Solutions Journalism Network and is funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and City University of Seattle.

This story was produced in partnership with the Education Lab, a Seattle Times project that spotlights promising approaches to persistent challenges in public education. It is produced in partnership with the Solutions Journalism Network and is funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and City University of Seattle.