It wasn’t the broken neck from a skydiving accident in 2011 that sent Timberly Eyssen’s life into a downward spiral. Instead, it was the prescription painkillers that would cost Eyssen her successful career in public relations and marketing, her apartment, many friends, and the life she once had.

After the accident, Eyssen was prescribed OxyContin, Vicodin and Percocet — addictive opioids — for her chronic pain. She said the medications left her foggy, depressed and lethargic. She found herself nodding off or zoning out in the middle of conversations. She lost jobs. Friends stopped calling.

But some days the pain in her neck was so bad she couldn’t get out of bed. She’d take 30 Vicodin to ease the pain. Any mental energy she had left was devoted to chasing pills. She found herself riddled with anxiety about how sick she’d be from withdrawals.

Enlarge

“The pain always made me drive right back to the opiates even though it was destroying my life,” said Eyssen. She became so desperate, she decided to “check out” and jumped off a bridge last year.

Police found her in a marina and pulled her out of the water. She woke up in a hospital under lockdown, wearing the green scrubs given to psych ward patients. While in outpatient treatment, she attended a therapy group where a man suggested she try Suboxone, a medication that would stop her cravings. Now Eyssen, 48, who has turquoise-dyed hair and talks in a Texas drawl, takes Suboxone daily. It’s given her a lot of hope. She’s off opioids. She’s renting a room. She’s alert and functional and preparing for a new career.

In Washington, and nationally, addiction treatment providers are turning toward medication-assisted treatments, such as Suboxone, to fight the country’s opioid crisis that claimed 116 lives every day in 2016 alone, according to federal numbers.

For about a year, there’s been an effort underway in Washington state to increase the availability of medication-assisted treatments. That effort has extended to Clark County, where social services, addiction treatment providers and even the county jail are turning to it in hopes of saving lives.

Enlarge

Unlike previous approaches, which have viewed addiction as a moral failing to be overcome, medication-assisted treatment recognizes the physiological realities of opioid dependence. Drugs like Suboxone cap the user’s opioid receptors. In turn, that prevents the patient from going into withdrawal while they undergo counseling and behavioral therapies to address their addiction. The user also won’t get high if they use opioids.

“It’s philosophical,” said Jared Sanford, CEO of Lifeline Connections, a Vancouver-based nonprofit that treats people with substance abuse issues. “You can compare (opioid addiction) to diabetes or heart disease. We should treat this as a chronic disease with medication.”

But despite the promise of this treatment, it’s in some ways more regulated than the addictive medications that caused the problem. Having it more widely adopted will require physicians and institutions to overcome a lingering stigma over addictions and mental health.

‘If you see a demand’

After learning about Suboxone, Eyssen checked herself into a rehab clinic in Oregon where the first stop was the detox facility. She spent 24 hours mired in pain and nausea as she underwent withdrawal.

Enlarge

She recalled some patients in the facility who were coming off of alcohol having hallucinations. Others moaned loudly in agony. Everyone was mean and miserable.

“It is the worst place I’ve ever been,” she said.

After detoxing, she was given Suboxone for the first time. She said the pain went away and the other withdrawal symptoms subsided. She didn’t feel the euphoria she felt from opioids, but instead felt alert and productive.

For most of the past year, Eyssen has gotten her medication from Columbia River Mental Health Services, a nonprofit that serves Medicaid patients. Craig Pridemore, CEO of the organization, said that since 2006 his organization has been offering methadone, a form of medication-assisted treatment that’s been used for decades in the United States.

Enlarge

Patients who use methadone to treat opioid addiction have to make a daily trip to a clinic to receive their dose. Drugs like Suboxone have less potential for abuse and can be prescribed and taken home by patients. Approved for use in 1981, the drug has been increasingly embraced and is recommended by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s also sold in the billions. It’s even outsold popular drugs such as Adderall and Viagra.

Pridemore said that Columbia River Mental Health has been offering buprenorphine, an active ingredient in Suboxone, since 2016 and about 40 clients are prescribed it.

“If you see a demand, you want to provide that service,” said Pridemore. “But there is a lot more need out there than is currently being met.”

Pridemore attributes the increased use of medication-assisted treatments to a recent public policy push. Near the end of the Obama administration, the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services received $11.7 million to respond to the opioid crisis.

According to Michael Langer, deputy director of the Washington State Health Care Authority Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery, nearly 3,000 new patients are on medication-assisted treatment as a result of the initial effort, double its target.

“That’s huge,” said Langer. The Trump administration has authorized a second year of funding and Washington is applying for a $21.2 million grant to expand the program.

Hubs and spokes

The state’s approach is modeled after a hub-and-spoke model used in Vermont to make medication-assisted treatment more available. Using the model, Washington set up six “hubs,” each a local organization versed in medication-assisted treatment and with a physician licensed to prescribe drugs like Suboxone. The hubs work with “spokes,” organizations that someone with opioid dependency might encounter, such as needle exchanges, hospitals and others.

Langer said Clark County’s Lifeline Connections received a $789,825 grant to serve as a hub for the program that’s brought in 255 new medication-assisted treatment patients.

Describing it as a “tool in the toolbox,” Sanford said that there are “many roads to recovery” and it depends on each patient’s circumstances if they’ll be prescribed a drug like Suboxone, Vivitrol or methadone. Those who are prescribed the treatment by Lifeline’s physician are expected to undergo counseling to resolve underlying behavioral or psychological issues.

“The research shows it works and we see that every day with our folks,” he said.

For the hub-and-spoke effort, he said Lifeline has partnered with both local hospitals, the needle exchange program and other social service nonprofits, as well as the Clark County Jail.

Chief Corrections Deputy Ric Bishop and his staff began offering re-entry programs to jail inmates wanting to break the cycle of recidivism. Bishop said medication-assisted treatment fits in with that effort.

Enlarge

He said the jail began offering the treatment in December and currently averages about 2.5 inmates per day who receive the treatment. He said that the treatment will help keep inmates from relapsing or overdosing after they are released. He said that the jail could expand the program, but first wants to partner with a local provider so inmates can continue on it after their release.

“This is just our first step,” he said. “Our next step is to help people who want to break the cycle in jail.”

Call the doctor

At PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center, rehabilitation specialist Dr. John Hart said he’s spent much of his 13 years there prescribing oxycodone and other opioid painkillers to his patients.

“The literature at the time said to increase dosage if the condition got worse,” he said. “What we didn’t know was we were causing cellular brain damage.”

He said that when he first heard of medication-assisted treatment, he dismissed it, thinking it was for “borderline criminal types.”

He now says he was wrong. His change of heart began around 2008 after attending a conference in San Francisco where he dipped into a talk on the treatment. He said he began to realize the treatment could help clean up the mess he had inadvertently helped to create.

“These are not addicts; these are pain patients,” he said. “They were put on narcotics by physicians.”

Afterward, Hart got a special license through the federal government to begin prescribing drugs like Suboxone. He says he has 200 patients, and has become an evangelist for the treatment by working on an initiative to train more providers.

To prescribe medication-assisted treatment, a physician or nurse needs to get a license from the federal government. According to Langer, there aren’t complete numbers on how many physicians are licensed in Washington because many choose not to be listed on a federal website. But he said the best estimate is about 2,000, an increase of 219 since last fall. In Clark County there are 28 licensed medical professionals.

Enlarge

“Stigma is a huge problem,” said Eric McNair Scott, vice president of the Southwest Washington Accountable Community of Health, of why more doctors don’t get a license to prescribe the treatment. “There is a stereotypical picture of someone who can’t control their behavior because of substance abuse.”

According to McNair Scott, numbers on opioid addiction and treatment aren’t exact. But he said that the number of Medicaid recipients in Clark and Skamania counties who’ve had at least one claim of prescription opioids is 14,066. Of those, 2,288 have been diagnosed with opioid abuse and 416 are being treated with medication-assisted treatment, primarily methadone. He said that those numbers are likely an undercount.

He said there are obstacles to expanding the treatment. He said that it makes no sense that doctors licensed to prescribe medication-assisted treatment are capped at 30 patients their first year, which gradually is lifted to 275. He also said it also makes no sense that a doctor needs extra training to prescribe a life-saving medication but can “dole out OxyContin to as many people” as they want.

But Sanford said that for medication-assisted treatment to become more available, there needs to be “physician champions” like Hart who can normalize its use. Sanford said that it’s especially important for more primary care physicians to be trained in its application because they can quickly spot and treat a patient with an opioid disorder.

Hart said there are still doctors wary of treating drug addicts, such as family doctors worried about “those people” in their lobby.

“This is a community problem,” he said. “We need to have the community (involved) in this problem.”

One drug for another

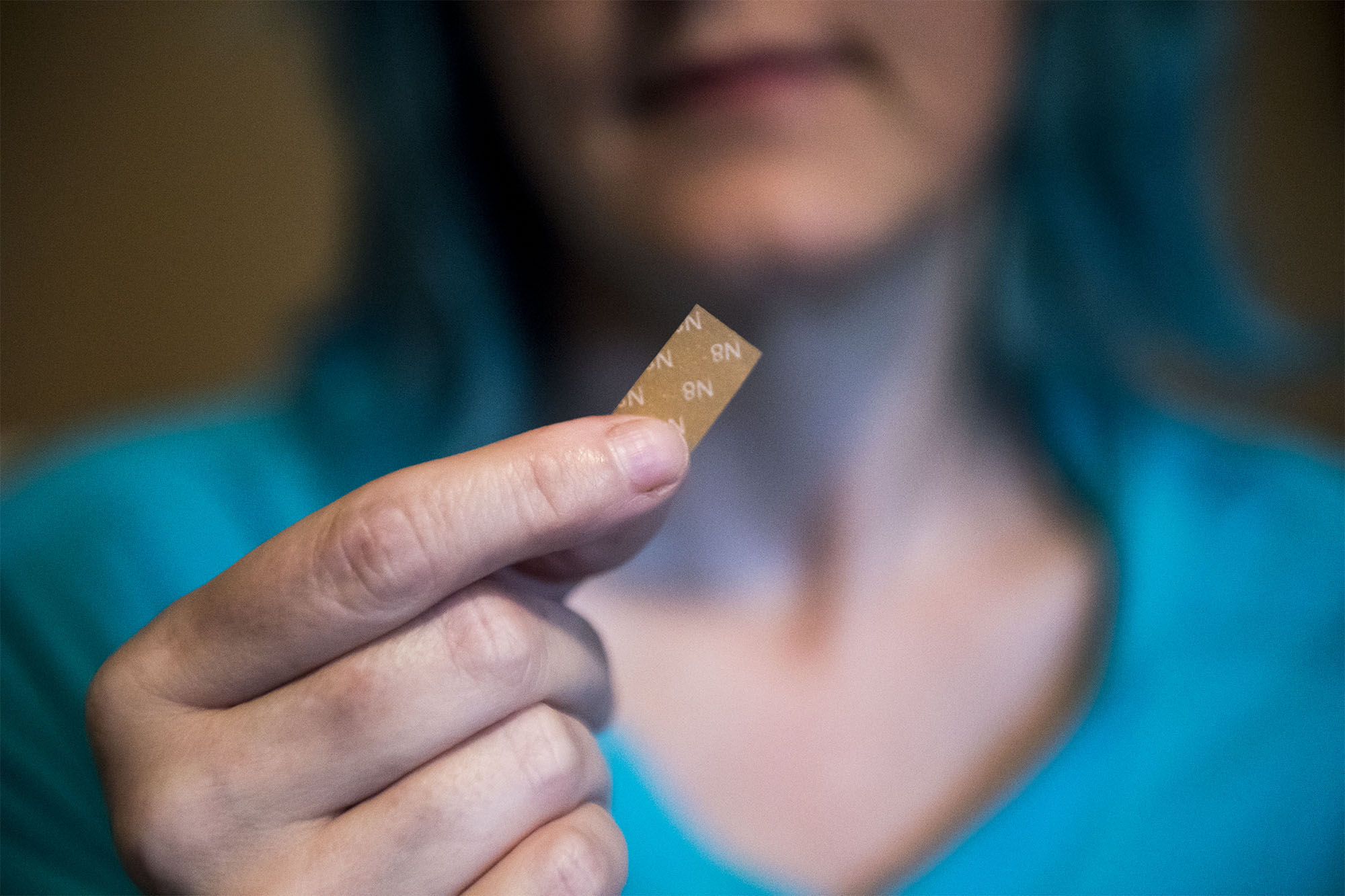

Once in the morning and again at night, Eyssen performs a ritual that keeps her life together. In the room she rents in the Salmon Creek area, she opens a thin plastic package labeled “Suboxone” and removes a film that she places in her mouth. It’s colored bright orange, like candy.

“It’s the most disgusting thing you’ve ever put in your mouth,” said Eyssen. She said she can’t talk for the 15 minutes it takes to dissolve the film; she uses the time to draw or write in her journal.

Enlarge

Although she’s on the right path, she worries about the perceptions of others.

“It’s really a big barrier when I go to a new doctor and I have to disclose (my condition),” she said, describing how a wall seems to come up and their demeanor changes. “There’s more of us out there than people really think.”

Sanford said that the research about opioid addiction and medication-assisted treatment should help to remove the stigma, but there are still those who continue to treat addiction as a moral failing. Many 12-step programs still won’t accept patients on medication-assisted treatment. Last year, former U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price came under criticism from researchers and practitioners for questioning the treatment.

“If we’re just substituting one opioid for another, we’re not moving the dial much,” Price said.

But Sanford said you’d never tell a diabetic to taper off insulin, and argues that medication-assisted treatment should be treated the same way.

Sanford said that some patients may try to abuse Suboxone. But the drug doesn’t produce euphoric effects, and it blocks other opioids that give users a high.

They could barter it or sell it on the street to opioid abusers to prevent withdrawals when they can’t get drugs. But he said that the potential of Suboxone, and other similar drugs, to save lives outweighs its minimal potential for abuse.

“What’s the alternative?” he said. “Should they just use heroin or OxyContin?”

Enlarge

Vicky Smith, a pastor and program director at faith-based Xchange Recovery Service, said her organization banned Suboxone from its several recovery houses because it was triggering to other clients. She also said some clients would get more on the street and would clog the septic system at its recovery houses with wrappers.

Xchange Recovery leaders changed their minds after they heard more success stories about Suboxone. Now they are better managing distribution of the medication.

“If it’s saving lives, that’s what matters,” she said.

McNair Scott said there are other barriers to the treatment being used more, like long wait times for appointments and a lack of coordination between service providers.

But he said the treatment is being embraced. He said in the spring his organization held a large conference on opioid dependence that was attended by service providers as well as local elected representatives.

“The shift that’s needed is starting to happen,” he said.

A reason to be hopeful

Earlier this year, Eyssen underwent foot surgery that required her to take Oxycodone, an opioid pain medication. She was riddled with worry that the opioids would even work or that once again she would get hooked on the medications she was on her way to kicking.

Enlarge

Reluctantly she tapered off Suboxone. As she prepared for the surgery, she felt the familiar rush of pleasure as the opioid painkillers were administered. She kept taking opioids during recovery, which tugged at her. But after again detoxing, she went back on Suboxone with no cravings and no problems.

“To me, it’s like an insurance program,” she said of Suboxone. “You could put a bottle of Oxy in front of me. It would do nothing. So why bother?”

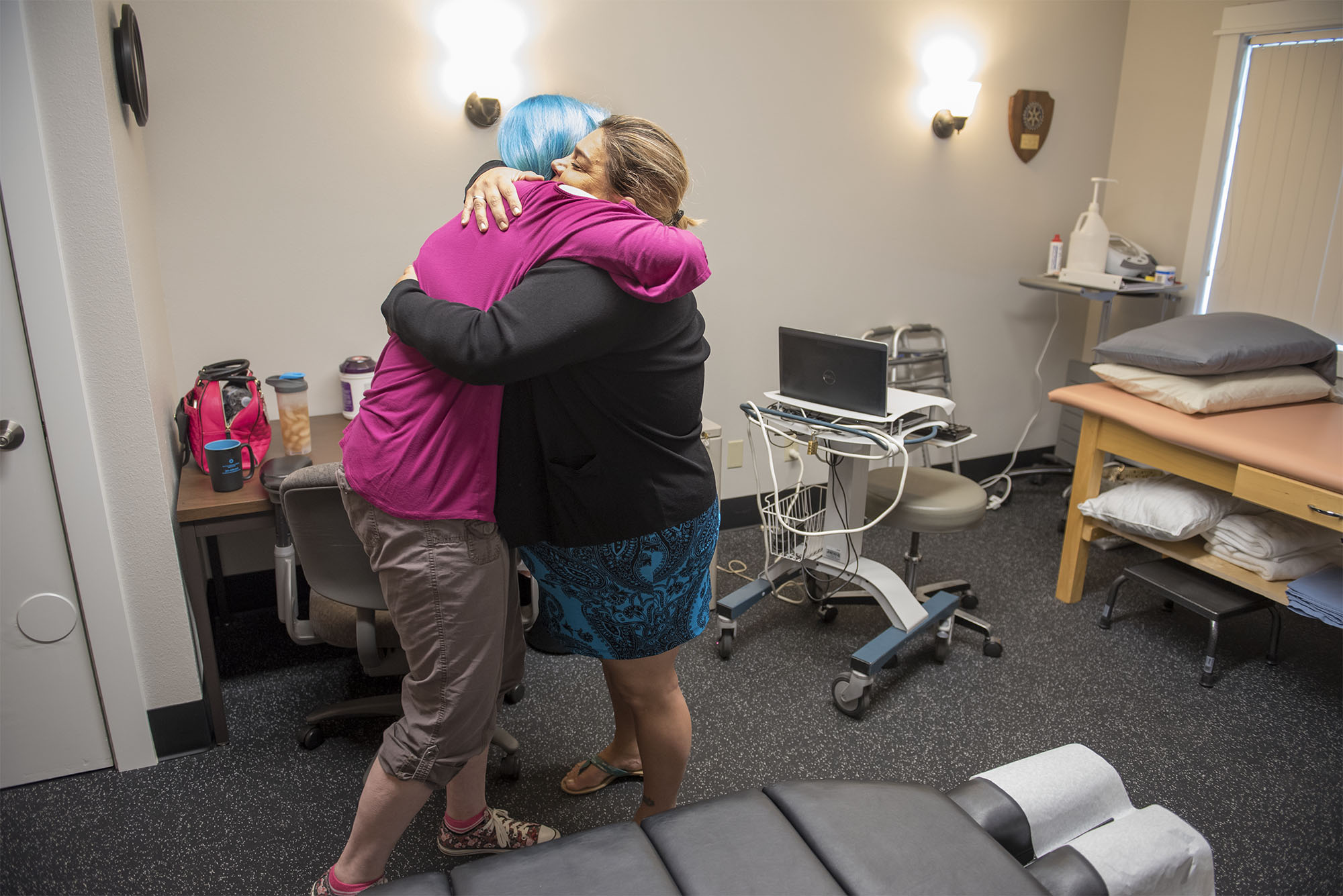

Enlarge

Steadily, Eyssen has put her life back together. She took a course at Battle Ground Health Care, where she learned how to better manage pain, which she does with meditation, chiropractic and massage. She volunteers there each week, goes to counseling, attends church, is making friends and is less anxious. Her room is decorated with memorabilia from the “Alien” movie series. Sometimes she does cosplay as Ellen Ripley, the film’s heroine, complete with a pulse rifle .

Recently, Eyssen passed her certification to work as a peer counselor and was offered a good paying-job. She now hopes to use her past struggles to show others what healthy recovery looks like.

“After eight years of spiraling down,” she said. “I’m 80 percent better and moving forward.”

Types of treatments

Medication-assisted treatment is predicated on the idea that drug dependency changes the physiology of the user and that medication, along with counseling and other therapies, should be used in their treatment. Such treatment is increasingly being turned to as a way to stem the nation’s opioid-addiction crisis. But not all treatments are the same.

Methadone: This medication has been used in the U.S. for decades. It’s a full agonist, meaning that it activates the brain’s opioid receptors, preventing the user from going into withdrawal. Because of its abuse potential, it’s dispensed in a regulated clinical setting.

Buprenorphine: A partial agonist, meaning that it doesn’t activate the user’s opioid receptors in a way methadone would. It also acts as an antagonist, meaning that it blocks other opioid receptors while reducing withdrawals. Because it has less of a potential for abuse, it can be prescribed.

Naloxone: An opioid antagonist that’s used to revive people overdosing on opioids. Often used under its brand name Narcan, it’s become commonly used by first-responders and law enforcement, including the Clark County Sheriff’s Office.

Naltrexone: An opioid antagonist that comes in a pill form or injection. It’s sold under the brand name Vivitrol, and is offered in some clinics in Clark County.

Suboxone: A brand-name drug that combines buprenorphine and naloxone.

If you are having suicidal thoughts, the following hotlines are available for free, confidential support.

• Southwest Washington Crisis Line: 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. 1-800-626-8137

• National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

Jake Thomas: 360-735-4515; jake.thomas@columbian.com; twitter.com/jakethomas2009