Lorraine Dunn said she feels like an airplane circling that needs to land. Her doctor told her she needs a home, so she can rest.

In her younger years, Dunn traveled a lot doing church ministry work, but now she has diabetes and other health issues and is feeling her 74 years. Lugging her black rolling backpack from apartment to apartment in search of a “rental miracle,” a safe and affordable place to live, she tires easily.

A circling plane eventually runs out of gas.

“I don’t even care if I have a bed or anything. I just want my own floor,” said Dunn, who is homeless.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

An increasing number of Clark County seniors face plights similar to Dunn’s. They’re homeless or on the brink of it — struggling to keep up with rising housing costs.

Did You Know?

• Outreach workers and volunteers found nine seniors living outside and 11 living in shelters during a single-day census of the homeless population in January.

• 38 percent of Meals on Wheels People participants in Clark County live at or below the poverty line.

• In 2012, 20 people age 65 and older participated in Share’s shelters, hot meals and ASPIRE (housing) programs. Last year, 76 seniors participated in those programs. Box type: n Council for the Homeless has seen a 23 percent increase in the number of homeless seniors calling for assistance. The call volume from those same seniors has increased 26 percent, meaning they’re calling more often.

• One in 10 seniors use food stamps.

Dunn recently visited her old stomping grounds, Parklane Apartments, where she said she lived in the early ’80s. She took the No. 71 bus from downtown to the Hazel Dell apartment complex because she heard it had three vacancies.

It turned out that all three apartments had applications, so she decided to keep looking and walked to another complex across the street.

Dunn says she gets by on Social Security income and widow benefits. After her husband died, she moved from Tennessee to Vancouver and began staying in a women’s shelter.

“I can’t find housing because it’s so expensive,” Dunn said. “Senior people by and large don’t have a lot of money.”

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

Those poor seniors are seeking help in several ways, evidence of a growing problem.

The Society of St. Vincent de Paul in Vancouver has gotten calls from more and more seniors needing help paying utility bills and rent. Meals on Wheels People started tracking the number of homeless seniors visiting its cafeterias. A handful of senior women living out of their cars in an east Vancouver church parking lot say they can’t afford rent. An increasing number of seniors stay at local shelters.

Car campers

The Council for the Homeless’ Housing Hotline is often the first place people call if they’re facing homelessness. The hotline saw more people age 62 and older calling for assistance last year. (Some agencies define “senior” as 62 or older while others consider someone who’s 65 or older a senior.)

Kate Budd, executive director of the council, said the common scenario is that a senior on a fixed income has been renting the same place for a long time when their rent goes up. They can’t afford the increase and can’t afford the $2,500 to $3,000 needed to move into a new place.

“The math just doesn’t get them to where they need to be,” Budd said.

It puts an already vulnerable population in a precarious situation. Most often, especially if they’re disabled, seniors don’t have the option to get a second job or go back to school to learn a well-paying trade and catch up with the cost of housing. Unless some safety net program catches them, they may find themselves without a place to live.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

“We’re hearing from seniors that they’re moving into their car most often,” Budd said.

By the numbers

• Baby boomers began turning 65 in 2011. The youngest boomers will have turned 65 by 2030.

• Every day in the U.S. about 10,000 people turn 65.

• By 2030, nearly one in five people will be 65 or older.

• About one in five seniors is widowed.

• Almost 16 percent of seniors are employed.

• About 90 percent of seniors have Social Security income averaging $19,826.

• Median household income for householders 65 and older: $46,082.

• Almost half of seniors have retirement income averaging $25,237.

SOURCES: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 5-year estimates

Jerry Lyle is one of those car-campers. He’s turning 67 soon and says he became homeless about three years ago while working in Ridgefield. The house he was staying at in Portland sold, and he didn’t earn enough to rent somewhere else. So, he decided to stay in his small white Chevrolet, a car he’s had since 1990.

Lyle’s days are defined by routine. He wakes up early and visits Starbucks to use the restroom and get coffee. Then he drives to the Vancouver waterfront and makes breakfast on a two-burner propane camping stove set on the hood of his car. He knows where to fill his water jug and which parking spots stay shaded throughout the day, and he knows many of the other people who car-camp along the waterfront — most younger but some older than him.

“It’s not that bad out here, but it isn’t that good, either,” Lyle said.

Winters are dreary and life can get lonely. Still, he’s lost his initial fear of living outside, and people are often “amazed that I maintain myself so well,” he said.

Lyle said he just started receiving Social Security income, along with a small pension, and hopes to save up enough money for a place to live before winter.

Housing competition

If Lyle tries to get a place that is subsidized, with an assistance program alleviating the cost burden for low-income people, he’ll face steep competition — particularly at complexes designated for seniors.

Vancouver Housing Authority and its affiliate, Columbia Non-Profit Housing, own or manage about a dozen independent living properties, all with waiting lists. Highland Park, a 55-unit property in the Van Mall neighborhood for people 62 and older, has 289 people on its waiting list. (People can be on multiple waiting lists for different properties.)

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

Turnover among these properties is low. Highland Park, for instance, had just one unit turn over in 2017. Once people secure a spot in one of the housing authority’s coveted properties, they stay there for a long time.

“In most instances, this is their last place,” said Leah Greenwood, director of property and asset management at VHA and executive director of Columbia Non-Profit.

She sees the problem as several factors working together: Seniors are the fastest growing age group in America. Many are on fixed incomes and can’t make more money, and when rents rise, they can no longer afford housing in the private market. Many work later in life to try to keep up with costs. Even as the rental market stabilizes, rents are often well above what seniors can afford, so they turn to VHA and other organizations with income-based properties. Hence, the long wait lists.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

The housing authority and other low-income housing developers use money from the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program and the state Department of Commerce to build projects. Neither currently prioritizes senior-based projects, Greenwood said. Homeless families and people with behavioral health issues have been big focuses in recent years.

“It’s influenced which new projects we take on,” Greenwood said.

REACH Community Development, for instance, shifted the focus of its second phase of Isabella Court in central Vancouver from seniors to extremely low-income families because federal funding priorities shifted.

Incomes pinched

An estimated 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day in the U.S.

“When you stop and think about that, that’s a whole boatload of people,” said David Kelly, executive director of the Area Agency on Aging & Disabilities of Southwest Washington.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

His agency, among its many roles, is the local government contractor for Meals on Wheels People and connects about 3,200 senior clients with services to alleviate the effects of poverty.

Low-income seniors don’t have money for a variety of reasons. Kelly said many haven’t done much retirement planning and rely solely on Social Security for income. According to the Social Security Administration, 23 percent of married couples and about 43 percent of unmarried persons rely on Social Security for at least 90 percent of their income.

“America is the lowest nation of the industrialized world on the principle of saving,” Kelly said.

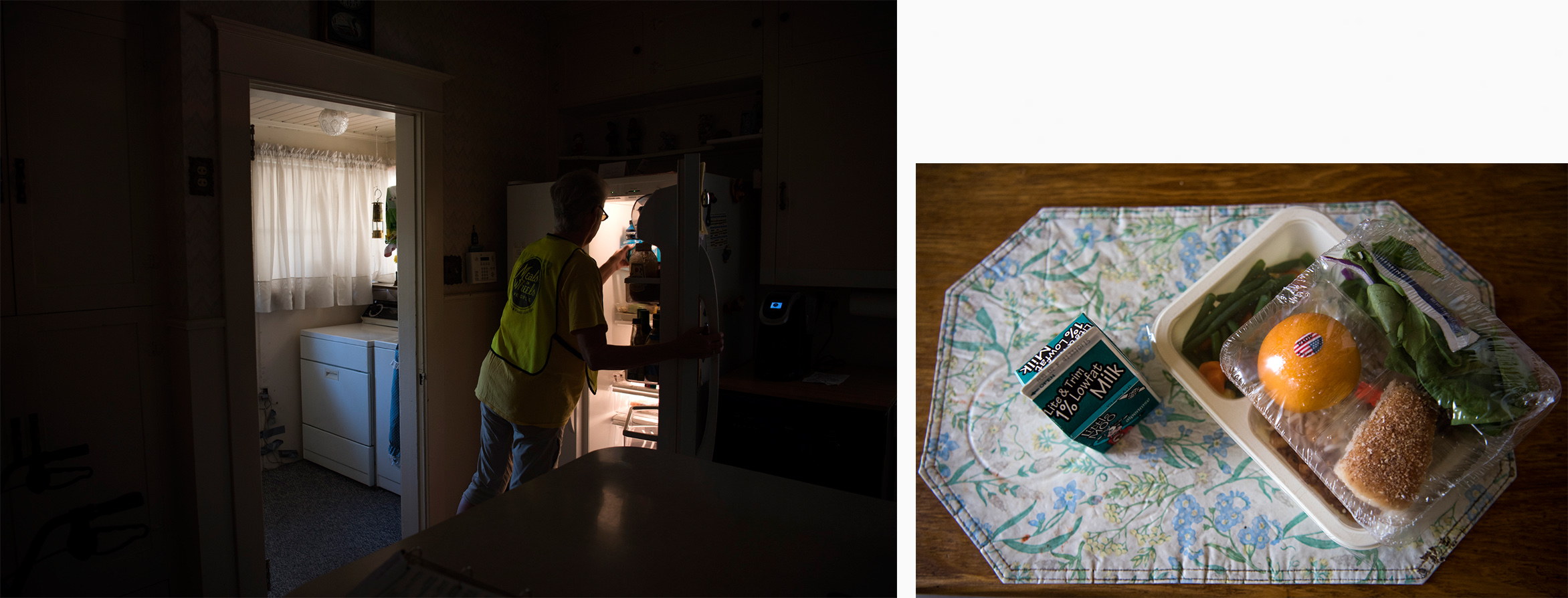

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

According to the U.S. Census, the percentage of seniors with retirement income has declined; about half of Clark County residents age 65 and older have retirement income. Meanwhile, the number of local senior-headed households living below the federal poverty level increased by about 32 percent between 2009 and 2016. (The poverty level is $12,140 annually for a single person and $16,460 for a couple.) And, the percentage of seniors using safety net programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, and Supplemental Security Income has risen.

Older single women — who, perhaps, are widows and get a portion of their spouse’s Social Security — struggle more often than older men.

Difficult transitions

Meals on Wheels has a well-known mission to prevent social isolation, but it also helps people remain in their homes as long as possible; having somebody deliver prepared meals and check on seniors means they may not be displaced from their home or need to go to assisted living.

On a recent Meals on Wheels driving route, volunteers John and Joyce Gentry visited 87-year-old Ted Cusic, who cannot afford to stay in his home.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

He never thought he would outlive his wife, Virginia. She died at age 77 on Memorial Day from cancer that she didn’t know she had. Without her and her income — her pension and Social Security — Cusic has to leave his home in Vancouver that he’s owned for about 30 years.

Cusic gets Social Security and benefits as an Army veteran, but he said he wasn’t able to save much for retirement. He worked various jobs, was a custodian at a middle school, did wood carving on the side and was a beloved security guard in Vancouver known for making passers-by smile with his goofy getups and cheerful greetings. He spent about a decade caring for his granddaughter.

Now, he’s navigating life on a limited income and trying to find a place to move.

“I’m kind of looking forward to it, but I’m not real happy about it,” Cusic said. “I lived here a long time. It’s going to be a whole new life for me.”

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

Reaching out

Greenwood said the community’s “big challenge” is to help a growing population of seniors who are going to rely more and more on subsidy. That means building more affordable places for seniors to live or providing more rental assistance. Recently, $1.2 million from Vancouver’s Affordable Housing Fund went to the Council for the Homeless to prevent seniors and other people from becoming homeless.

Get help

Are you a senior who …

• Needs help with housing? Call the Housing Hotline at 360-695-9677.

• Needs to get connected to supportive services? Call the Area Agency on Aging & Disabilities at 360-694-8144.

But, Kelly said, solutions also include making seniors aware of what resources and services they may be eligible for; it’s helping seniors help themselves. The Council for the Homeless recently formed a partnership where the Area Agency on Aging & Disabilities has a staff member working at the Housing Solutions Center to do just that, guide people toward options.

“You don’t leave opportunities unknown,” Kelly said.

Patty Hastings: 360-735-4513; twitter.com/pattyhastings; patty.hastings@columbian.com