High school graduation season has begun. At high schools across Clark County, seniors are preparing to cross the stage to collect their diplomas and begin their next chapter. To mark this milestone, The Columbian is profiling six outstanding seniors from the Class of 2016 who have scaled significant obstacles, as recommended by their teachers, counselors and principals. On Monday, we’ll publish our annual list of high school commencement and baccalaureate ceremonies.

Dustin Zimmerly

For Dustin Zimmerly, running isn’t a time to think. It’s a time to zone out.

“You just go off in your own world,” said Zimmerly, 18. “You just go blank. You don’t have to think.”

That came in handy for Zimmerly a few years ago, when his father, Donald Zimmerly, died in a motorcycle accident.

Dustin Zimmerly was close to his father, who made sure to attend all of his son’s track meets and motocross events. Zimmerly’s mother was in and out of his life at that time and the two didn’t have the best relationship, so after Donald Zimmerly died, Dustin stayed in the house with his brother, who is about four years older.

Dustin Zimmerly

- Extracurricular/interests: Running and motocross.

- Future plans: Attending Eastern Oregon University.

- Career aspirations: Own a running apparel store.

- Role model: Father.

Just the two of them were home on the night of Aug. 1, 2014, when they got a knock on the door and were told of the accident. Once Zimmerly composed himself, he had to start making calls to let people know his father died, including calling his mom.

“It was the worst night of my life,” he said. “I couldn’t sleep for a week. I couldn’t think straight. I couldn’t talk.”

Looking to live in a more controlled environment, he moved in with his paternal grandparents in Ridgefield, where he’s lived since. He got a boundary exception to stay at Camas High School, and wakes up every day at 5 a.m. so he can leave by 6 to make it in time for his 6:40 a.m. zero period weight training class.

He also stays late most days for track practice. Before every race, Zimmerly writes “in memory of dad” on his wrist. It keeps his dad with him while he runs, and it will allow his dad to go to college with him, as Zimmerly earned a track scholarship from Eastern Oregon University in La Grande, Ore.

Zimmerly said he’s learned to surround himself with positive people and never think about doing bad things to yourself or other people. He also learned the benefit of zoning out.

“It was a really big part of why I stayed sane,” he said.

— Adam Littman

Kyla DeGrandpre

Kyla DeGrandpre has gone to bed hungry plenty of nights.

Although she and her two brothers ate free breakfast and lunch at school, her family routinely went hungry at home.

Throughout her middle and high school years, Kyla’s family “moved around a lot” between Vancouver, Washougal, where her grandmother lived, and Stevenson, where rent was cheaper.

Kyla DeGrandpre

- Extracurricular: Varsity softball, four years; varsity junior captain and varsity senior captain.

- Future plans: Clark College for two years, then transfer to WSU Vancouver.

- Career aspirations: Elementary school teacher.

- Role models: Rodena Cadiz, her mother’s friend who took her in; Natalie Sangalli, her health teacher at Hudson’s Bay High School.

To keep some stability in her life, she stayed at Hudson’s Bay High School. She awoke at 4 a.m. to ride two buses from Stevenson to school. She learned to live without enough — enough food; enough love.

She reached a breaking point her freshman year and left home.

“I called it quits. I knew how I wanted to be treated,” she said.

Her friend’s mom, Rodena Cadiz, invited her to live with her family even though money was tight. “Rodena taught me how to be a better person,” Kyla said.

When Kyla heard her two younger brothers were in foster care, she tried moving home. She said she remembers thinking, “Maybe there’s a chance to get my family back together.”

But the family’s dysfunction had escalated, and her relationship with her parents was more strained. “They sucked everything out of me,” she said.

Softball provides stability in Kyla’s life. She started playing in fifth grade. As a freshman, she made varsity. She was junior captain last year and senior captain this year. That meant extra responsibility. It also meant she didn’t have time to get a job. Playing high school sports was tough without money. She broke her bat and couldn’t afford a new one. She had to borrow a glove from the school.

“I didn’t like to ask for things,” Kyla said. “I didn’t come to school much in freshman year. I didn’t care.”

Kyla’s health and fitness teacher, Natalie Sangalli, encouraged her to keep up her grades.

“Sometimes, it’s been hard to stay in school. Now, I don’t let myself fail. I don’t have time for this.”

After failing two classes freshman year, she had to make up those credits in summer school.

Kyla found stable housing by moving in with her boyfriend’s family about a year ago. There is always enough food. The school’s family resource center gives her Goodwill vouchers for clothing.

She’s graduating in four days. She completed the financial aid forms and applied for college without her parents’ help. Because she gained independent student status in her freshman year, she qualifies for free tuition from the state’s College Bound program.

Kyla plans to become an elementary school teacher who can influence children facing enormous obstacles, like she did. She wants to stay in Vancouver. She dreams of a stable life: owning a home, having a reliable car. She wants to be a mom someday.

“I want those basic necessities — like a family. I know how I want my life to be,” Kyla said. “I think helping kids will make me a better person. I’ve always been the person being helped. I’d like to be the person helping someone. I’m not going to settle for the life I’ve had.”

— Susan Parrish

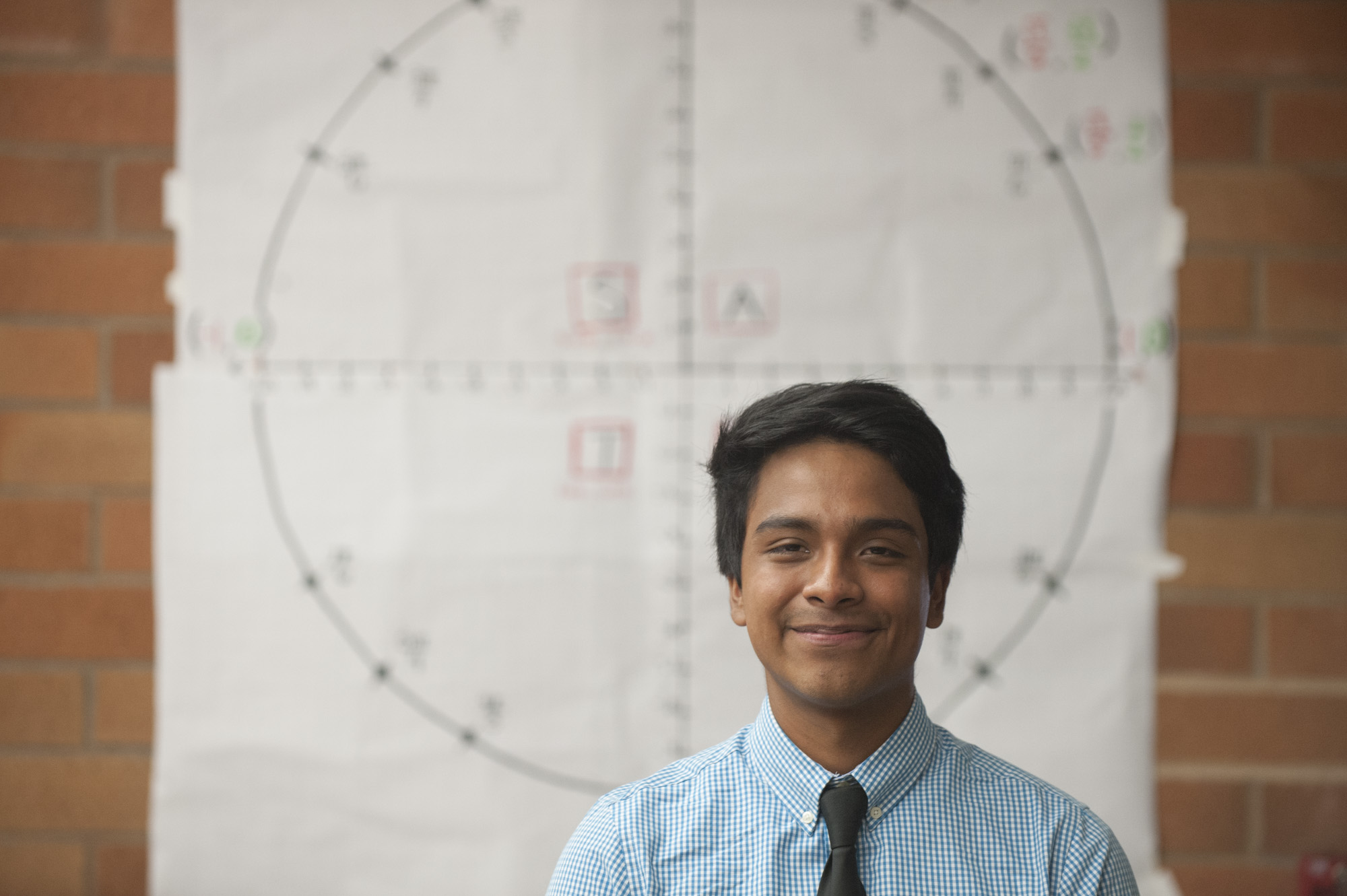

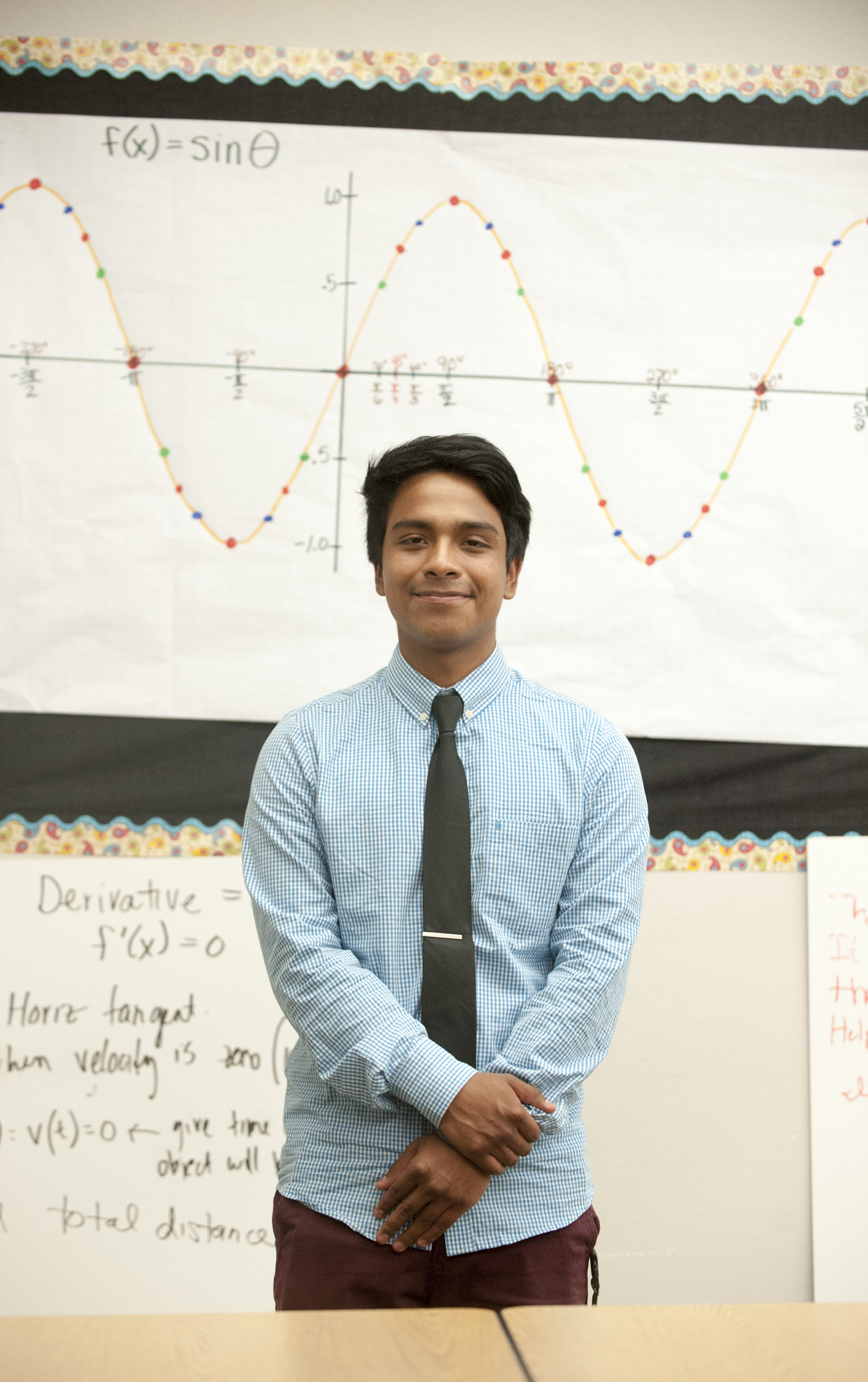

Benny Giron

Benny Giron wants to be an entrepreneur in the renewable energy field.

He got an early start at age 7, when he picked up an empty bottle and realized he could redeem it for a nickel to help his mom buy food. His family lived in Oregon at the time.

“We got into the recycling business,” he said. “We picked up any bottles with ‘5 cents’ on it.”

Benny Giron

- Extracurricular: varsity soccer, team captain, cross-country, photography.

- Future plans: Study engineering at WSU Vancouver.

- Career aspirations: Entrepreneur in renewable energy field.

- Role model: His brothers, Theo and Jimmy.

Giron is the youngest of nine children. His dad left when Benny was 6.

“Throughout that time, I was so ashamed. I learned to get past that.”

Although money was scarce, his family had enough.

“My mom would always provide for us, no matter what,” Giron said. “There’s always food on the table, clothes on our back, a roof over our heads.”

He’s good at math and working with his hands. He thrived in the Geometry in Construction program at Evergreen High School, where he helped build a house for a Habitat for Humanity family.

For the past two years, he’s worked for his oldest brother, Theo Giron, who owns a roofing business.

“I begged my brother: ‘Let me work for you,’ ” Benny laughed.

During the school year, Giron works about 20 hours a week. His aptitude for computers and ease with people make him a valuable employee in the office. He modernized the company’s inventory by creating QR codes and recommended his brother buy scanners to read the codes and simplify inventory. In the summers, Giron works full time, dons a hard hat and joins his brothers on scorching rooftops.

Giron’s family is adamant about his future.

“My brothers don’t want me around the roofing industry. They tell me, ‘You can go to college.’ ”

When Giron receives his Evergreen diploma, he’ll be the fourth sibling to graduate from high school.

Next fall, he will become the first person in his family to attend college when he starts classes at Washington State University Vancouver. He plans to pursue manufacturing engineering to develop his own products in the renewable energy field.

He’s already earned some college credits from passing rigorous Advanced Placement exams. He also completed a STEM internship at SEH America earlier this year.

“I know education is the key.”

— Susan Parrish

Alexann Tureman

Alexann Tureman has been legally blind all of her life, but her visual impairment hasn’t stopped her from pursuing her dreams.

She took second in state in the 50-meter freestyle as a swimmer at Hudson’s Bay High School. She is a powerlifter who competed in the International Blind Sports Federation World Bench Press and Powerlifting Championships.

To earn pocket change, she works as a barista two afternoons a week in the Lion’s Den Coffee Shop on the campus at Washington State School for the Blind.

Alexann Tureman

- Extracurricular: Powerlifting, swimming.

- Future plans: Walla Walla Community College, then transfer to Spokane Falls Community College for its PTA program.

- Career aspirations: Physical therapy assistant.

Now Tureman is focused on her next goal: becoming a physical therapy assistant.

“I’m really excited to go to the next chapter of my life,” she said.

After graduation next week, she’ll move home to Walla Walla and live with her family for a year while she attends Walla Walla Community College. She’s lived away from her family for seven years in order to attend the state school in Vancouver. She’s flown home every weekend, but she said those weekend visits are not the same as being home. She’s looking forward to hanging out with her parents and her sister, Sydney, 14.

When asked if being blind has placed difficult obstacles in her path, she shrugged: “I’ve been like this my whole life. This is all I know. Never give up. Keep at it, no matter what.”

Then, as she steamed milk for an Americano, she added: “If I could see, I’d be a surgeon.”

— Susan Parrish

Drew Beckley

Drew Beckley wasn’t always comfortable with attention, but he had to get used to it. That’s what happens when you show up to your sophomore year of high school riding a scooter.

Beckley, 18, found out he had osteoarthritis in both ankles while in seventh grade. He gave up more physically demanding sports such as basketball, soccer and baseball by his freshman year of high school, although he still didn’t want to tell a lot of people about the arthritis.

The week before his sophomore year, with his arthritis getting worse, his mom convinced him to use his scooter at school. It’s a scooter with a padded area to put up one leg while the other pushes. Beckley alternates which leg rests and which pushes throughout the day.

Drew Beckley

- Extracurricular/interests: Young Life, golf, swimming.

- Future plans: Attending California State Polytechnic University in the fall.

- Career aspirations: Research and development.

- Role models: Scientists John von Neumann, Albert Einstein and Michael Faraday.

“There were five questions from people every period,” he said. “That was hard.”

The questions continue out of school, too. Beckley said he’s used to dirty looks from strangers when they see his tall, slim frame park in a handicapped parking spot or use an electric scooter in the grocery store.

To fill his sports fix, Beckley took up swimming and golf, sports he didn’t have much interest in before because they are so individualized. He didn’t play golf in ninth grade because he was too embarrassed to ride around in a cart while everyone else walked. Beckley said that was a silly worry, and now he regrets missing out on an extra year with the golf team.

Beckley said while he’s disappointed he had to give up sports, he knows there are plenty of people worse off than he is. He’s even making the most out of riding his scooter around. While it doesn’t handle non-paved areas too well — and even on paved ground, riding over a pebble can send him tumbling — he recently rode it down a 10-foot drop into a foam pit at a skate park.

Friends have suggestions for the scooter, too, such as lighting it for Christmas and decorating it as the Mayflower when Beckley and his girlfriend dressed as pilgrims for homecoming. However, there’s one suggestion he gets more than any other.

“If I had a penny for every time someone told me to put a motor on it, I’d have enough money to put a motor on it,” he said.

— Adam Littman

Perla Mendez

When Perla Mendez was growing up, her father told her when she hands him her high school diploma, his job of raising her is half-over. When she hands him her college diploma, his job is done.

Mendez, 18, is almost halfway there.

She will walk in graduation this year, her fifth in high school, a year after she turned down the chance to do so. Mendez wasn’t on track to graduate last year — she said she had a rough freshman year and it took a while to rebound — but she was offered the chance to walk thanks to Kevin’s Law. The law was voted into the Revised Code of Washington in 2007, and it states that any student receiving special education or related services can walk in a graduation ceremony after four years with his or her age-appropriate peers and receive a certificate of attendance.

Perla Mendez

- Extracurricular/interests: Soccer.

- Future plans: Moving to California with family, and then college.

- Career aspirations: Teacher.

- Role model: Father.

“It would feel weird to be congratulated when I wasn’t done,” she said, adding that she wasn’t sure how she would have faced all her family and friends who came to graduation when she told them she walked but wasn’t graduating.

Mendez said she struggled in school for a long time.

“School has been fun, great and hard all at once,” she said. “I’m the kind of person who thinks the alphabet and numbers should never be mixed.”

Mendez said math story problems gave her a lot of trouble, but her test scores were too high to be sent to an easier class.

“I felt like I wasn’t smart enough, like I couldn’t be in a regular class,” she said.

She also said she has trouble asking for help, which led her to fall behind her classmates.

– Susan Parrish

Photo Gallery