On an early November morning, light seeps into the gymnasium. The fluorescent lights are humming, slowly warming up as Donna Pinaula tries to get her 7-year-old son dressed.

Johnny Pinaula doesn’t want to get up and go to school. Neither does his sister, 16-year-old Shyanne Tanguileg. They’re snuggled next to each other on green mats about 3 inches thick with a mess of blankets piled on top of them. Johnny lies limp, shielding his eyes from the lights, as Donna pushes his shoes on.

Other families are stirring in their similar makeshift beds spread across the gym. Donna, 38, and her children are among the many families who’ve spent nights on the floor at St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the host of the Winter Hospitality Overflow shelter. Last year, the family shelter served 506 people, including 157 children.

“I’m not going to school,” Johnny says.

“There’s no life without education, Son,” Donna says.

She wants her children to go to college and vows that they will never be homeless again. She tells them not to feel bad for themselves.

“If you stay with the negativity, you get tired,” Donna says.

Donna and her two sleepy children walk across the grass, as cars rumble along Gher Road, to catch the No. 72 bus. It’s dark and raining. It’s the kind of weather where the rain builds up, forming mini lakes along the roads.

Donna, though, is used to walking outside. She keeps her head up, letting the rain splatter her weathered skin. When she smiles — which is often — a freckle crinkles under her left eye.

They take the bus to an Orchards apartment complex, where three of Donna’s other children live with her father and stepmother. This is the brief time she sees the rest of her children. They hang out on weekends and spent Thanksgiving together.

Ozzy Pinaula, 9, screams at Donna to leave him alone and locks himself in a bedroom. They all miss the bus to Orchards Elementary School. Eventually, Ozzy and her other son, Robert, 10, get a ride to school from a relative. Family tensions are high, and Johnny doesn’t get to ride in the car with them. Donna walks him the half-mile to school.

The pair detour through a well-worn dirt path in a field that leads to Fred Meyer, where they pick up drinks and a sandwich for Johnny. In the summer, the family lived in a tent in that field. Donna slept with a hammer and a BB gun. They had a floppy-eared bunny named Thumper and a rug underneath their mattresses. It was homey, Donna says.

At Orchards Elementary school, Johnny is quickly ushered to class. Donna plops down on a chair in Jennifer Beeks’ office. Beeks, outreach coordinator at Orchards Elementary School, sees lots of families in transition. The Winter Hospitality Overflow shelter and the Share Orchards Inn are both within Orchards’ school boundaries, she says.

Beeks asks Donna how the house hunt is going. Donna has a housing voucher through the Vancouver Housing Authority, but it’s tough to find a landlord that will rent to her and accommodate all of her children. She told the Salvation Army she would drop her résumé off at 9:30 a.m. She’s late for that and holds off on visiting Clearview Employment Services, a nonprofit serving those with barriers to employment.

I don’t think my youngest son understands the homelessness. All he knows is that he’s safe, happy, fed, cared for. Donna Pinaula

During the day, there are a lot of places for Donna to go. She’ll take the bus to Clearview Employment Services, Goodwill, the library or to drop off résumés at places around town.

The family reconvenes at St. Andrew, which reopens to clients at 6:30 p.m. Johnny makes a beeline for the foosball table, where he joins a game with his friends.

“I don’t think my youngest son understands the homelessness. All he knows is that he’s safe, happy, fed, cared for,” Donna says.

Traci Johnson has been a WHO volunteer for five years, and she’s a teacher at Shahala Middle School.

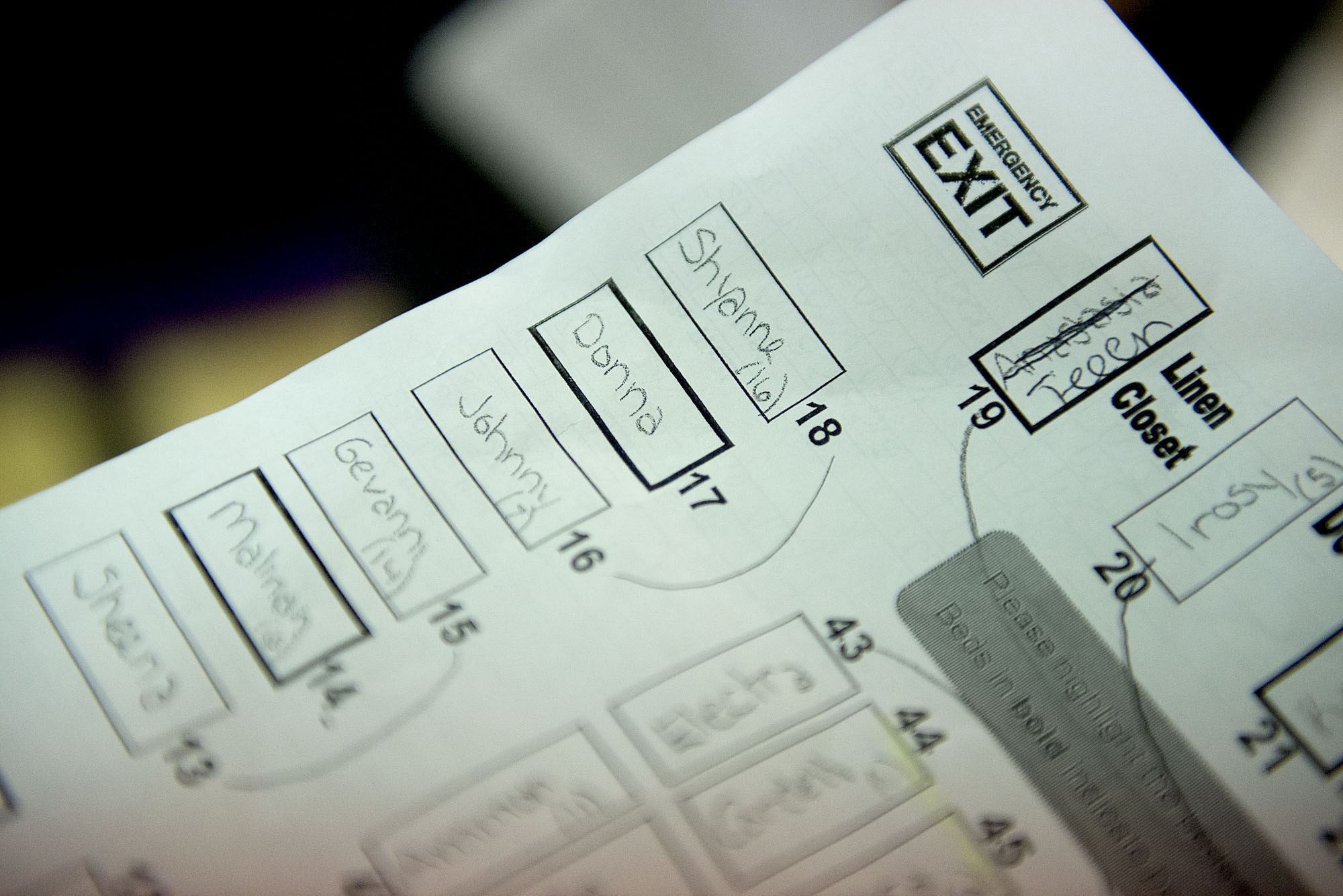

“Until they’re about 10 or 11, it’s a big slumber party, and it doesn’t bother them,” Johnson says. She holds a clipboard that shows where everybody is going to sleep in the gym.

Donna dreams about having a house with a backyard for her boys to run around in.

“You can’t be picky, Mom,” Shyanne says.

Donna’s housing voucher through the housing authority’s Shared Homes program expired this week, but she believes she’ll get a 30-day extension. She’s also checking with the YWCA on housing leads.

To get ready for the night, the families collect plastic bags full of linens and drag them across the gym floor to their assigned spot. There are nine families staying tonight.

Even though we’re homeless, we don’t stop living. We don’t stop learning. We don’t stop laughing. We don’t stop helping others. Donna Pinaula

“Of this nine, two have fathers present,” Johnson says.

Donna has a no-contact order out against Johnny’s father, her husband. The fathers of her other children are out of the picture.

“I’m working on a divorce and starting my life over with my kids,” Donna says. She uses a domestic violence grant through the Clark County YWCA.

Having her own criminal record, it’s tough to move forward. With a history of fourth-degree assault and DUI, Donna believes employers see her as an angry drunk.

After setting up the bed, Donna gets Johnny to stop running in circles around the gym with the other kids. They snuggle on the mats and play games on their phones.

“Even though we’re homeless, we don’t stop living. We don’t stop learning. We don’t stop laughing. We don’t stop helping others. It’s just not having a roof and not having a vehicle and an income,” Donna says.

At 9:30 p.m., the lights go off.

Patty Hastings: 360-735-4513; twitter.com/pattyhastings; patty.hastings@columbian.com