BATTLE GROUND — Dan Biscoe couldn’t help but cry.

Rain poured down outside as he sat on the $6 couch he’d bought at Goodwill two days after moving into his new apartment at Alder Pointe. He opened his blinds and stared at a spot across the street, a line of evergreen trees behind Walmart.

“That’s where I lived,” he said. “I never thought I would get in here. This place wasn’t even a thought.”

When Biscoe, 50, found himself without somewhere to stay last summer, he set up camp in the woods behind the store on private property belonging to a then-vacant house. He felt safe and secluded there. While he worried about returning from work to see all of his things taken, he felt like it was somewhere he could exist without being seen. It was, until he returned from work one day to find a business card on his lawn chair.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

The card belonged to Amanda Clark, a housing coordinator for Vancouver-based Council for the Homeless. She heard about people camping in the area, and she had gone around handing out her cards and introducing herself to those in need of help in Battle Ground.

While homelessness continues to be one of Vancouver’s most contentious issues, the number of people without homes in Clark County’s small cities is increasing and becoming more visible. The Council for the Homeless and other agencies are looking to expand their limited services to meet the growing need in the county’s far-off underserved areas.

“We need to go out and meet them where they are, and increasingly they are outside the city of Vancouver,” said Kate Budd, the nonprofit’s executive director. “It’s something that, for these smaller communities, is new.”

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

Importance of outreach

Biscoe was two classes away from finishing his land surveyor courses at Clark College, but a back problem forced him to get surgery. Because of the surgery, he couldn’t maintain 3.5 acres of farmland belonging to an elderly woman who allowed him to stay in a trailer on her property. She kicked him out.

“I was trying to be as normal as you can be when nothing is normal in your life,” Biscoe said.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

He worked in the produce section of the Walmart he lived behind and bathed with wet wipes or a garden hose at his church when he could. Biscoe would sometimes ask one of the few co-workers who knew his situation to walk by and do a “smell test” before he’d start his workday.

Biscoe did not know about Council for the Homeless until he got Clark’s card.

“It was such a blessing, though, the way they reached out and helped me without judgment,” he said. “When you’re homeless, you’re judged.”

When people call the council seeking help, they’re asked where they last lived. Last year, 253 homeless people claimed a small city as their last permanent address. While the number of callers has remained about the same for the last five years, the number of homeless students in these areas has shot up. By comparison, 1,613 homeless people said their last permanent address was in Vancouver city limits.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

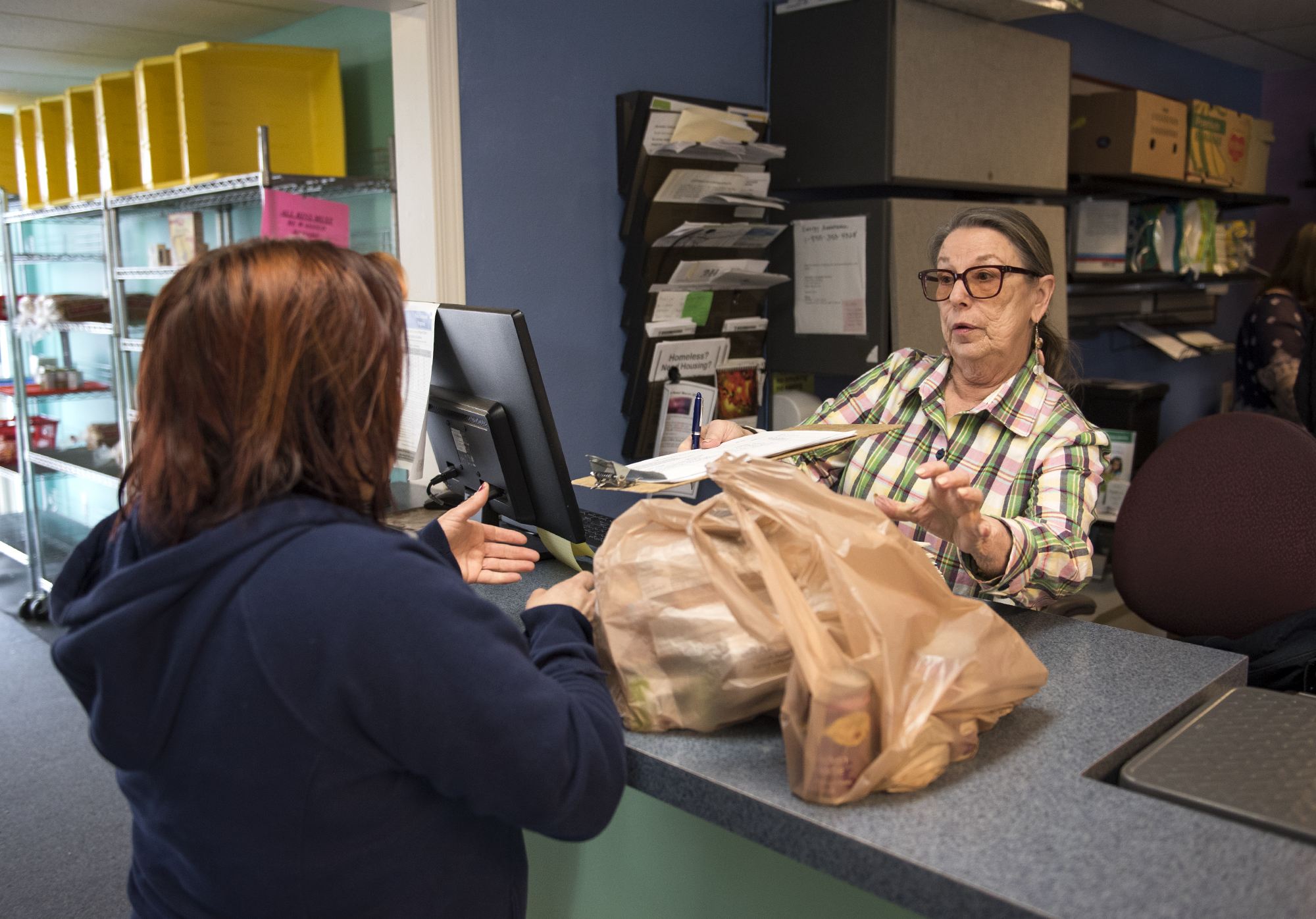

Clark meets with people at North County Community Food Bank off Main Street in Battle Ground. Another housing coordinator meets with people at St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Washougal.

“There’s a perception that it doesn’t occur out here,” Clark said from her makeshift office at the food bank. “It’s less visible, but just because it’s less visible doesn’t mean it’s not happening.”

The food bank’s executive director agreed.

“Homelessness is growing throughout Clark County,” said Elizabeth Cerveny, who is also a city councilor in La Center. “North county is no different.”

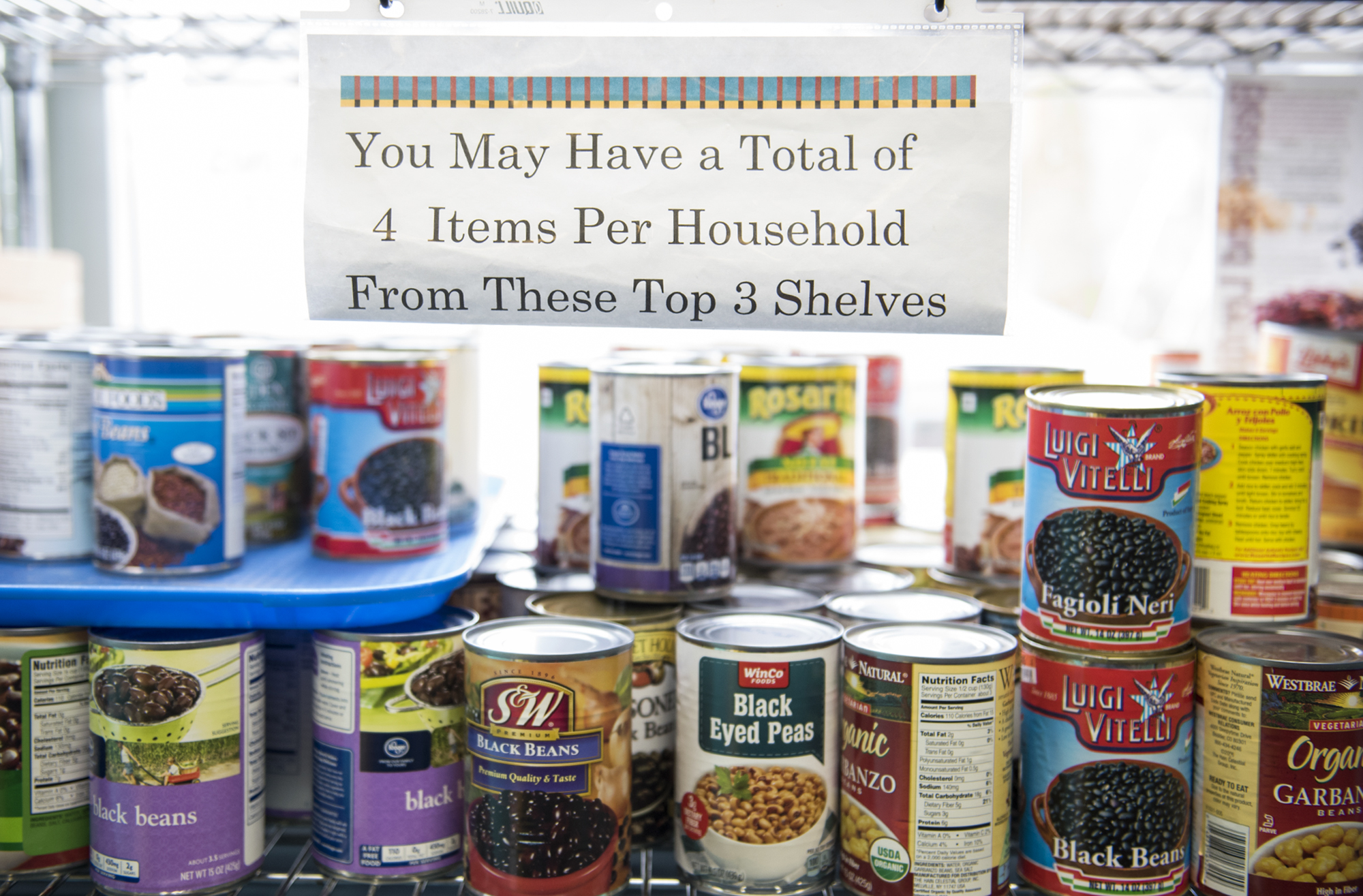

Cerveny said she has 220 homeless clients from Battle Ground and beyond. The food bank is one of the few resources this far north. It stocks supplies, blankets and gloves, along with waterproof totes full of ready-to-eat foods, for its homeless clients.

“Even though we’re small we try to make the best of the limited square footage,” Cerveny said.

Need for services

Before Clark started doing housing assessments about a year ago, the food bank would let people use the computer and phone to contact Council for the Homeless. There wasn’t much more they could do.

On a recent Wednesday, Clark spoke with a man at the food bank who said he needed time to think about whether he wanted help. People often say they’re either not interested in going to the council’s central Vancouver offices on Andresen Road or can’t make the trek. For those in the small cities, Council for the Homeless is still an unfamiliar, irregular presence.

Budd said that the number of homeless people who call the Housing Solutions Center claiming they last resided in one of the small cities is one of several metrics used to measure homelessness. It’s considered an undercount because not everyone who’s homeless engages with the Housing Solutions Center.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

However, more solutions could be coming. House Bill 1570, which increases document recording fees to generate more money for homeless services, awaits Gov. Jay Inslee’s signature. Advocates say the extra funds could be used to expand services to outer areas and create more satellite offices.

Jamie Spinelli is a case manager with Community Services Northwest, and when her hours increased, she decided to use that extra time to reach out to people in Clark County’s outlying areas. Spinelli was with Clark that day she left the business card on Biscoe’s lawn chair. They often pair up to do outreach work.

She gets referrals and combs local Facebook threads where people talk about homeless people or encampments. Many assume that people go where there are services, but “most people stay where they’re comfortable,” she said, adding that it’s disheartening to see people talking online about how they should stop serving homeless people to make them go away.

“People will just stay there and not be served,” she said.

Placing people into housing in the small cities is more difficult because there are fewer options. She said Vancouver has had more time to absorb the fact that there is a housing and homelessness crisis and to do something about it.

“The hype about it is newer for the outlying areas,” she said, adding that people lack education about what homelessness is and what it looks like.

Spinelli also volunteers with Food With Friends, a grass-roots nonprofit whose mission is to fill gaps in services and which runs a shower trailer. She’s eying places that could host the trailer in the small cities.

‘Feels like home’

Biscoe feels tied to Battle Ground, where he’s lived off and on since 1987. His children and grandchildren live here, and his job is here, so remaining in the city was important.

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

Biscoe recently got his lease renewed for his one-bedroom apartment at Alder Pointe. He got a job with more hours at Andersen Dairy and is making ends meet, enough to pay his $1,000 monthly rent. When he saves up enough money, he wants to go back to school and finish those land surveyor classes. This summer he’s looking forward to going to church camp in Turner, Ore., and camping for fun, not survival.

“All those people who were kind to me … they didn’t have to,” he said. “This feels like home.”

City offers growing number of services to those in need

By PATTY HASTINGS and ADAM LITTMAN

Columbian staff writers

WASHOUGAL — For a portion of Alex Ortiz’s junior year at Camas High School, he’d wake up his younger brother and sister at around 3:30 a.m. and catch MAX light rail from Gresham, Ore., to Portland, where they’d take buses the rest of the way to Camas.

Ortiz, now 18, and his family were living in a shelter then, the third time they had been homeless. After three years on a wait list, Ortiz’s family moved into a home in Washougal before this school year.

They primarily got help from Vancouver Housing Authority and Share, which are the largest local providers of subsidized housing and homeless services. The Ortizes also took advantage of free weekly meals at Refuel Washougal, one of a growing number of resources in the city. Washougal has been proactive in bringing in services and showing empathy for homeless people.

Rose Jewell, assistant to the city administrator and mayor, said that Washougal feels a responsibility to address homelessness. The city collaborates with churches, businesses and other groups to provide resources that a city of its size wouldn’t normally have. The community is small and intimate enough that people who want to help often just call or drop things off at City Hall.

“Everybody is starting to raise up their hand and say, ‘this is what I have,’ ” said Jewell, who is also a Refuel board member. “It’s a matter of knowing your community and knowing where to send people. … There’s a lot of people who want to help.”

Washougal is working on a waterproof resource guide that lists all of the places where people can eat, take a shower or get rent assistance in the area. It would be an east county version of the Pocket Guide available around Vancouver. At Refuel’s free meal Fridays at the Washougal Community Center, people can get free clothing and hygiene products. Jewell said the nonprofit has led the charge in getting various groups to work together to provide solutions.

“One great aspect of rural communities, like Washougal and Camas, is their ability to get all the players at the table at one time to discuss a realistic solution for a community crisis,” Melissa Baker, Housing Solutions Center director for Council for the Homeless, wrote in an email.

This winter, the city and Refuel teamed up with St. Matthew Lutheran Church to establish the first emergency severe-weather shelter outside of Vancouver at the community center. When snow and severe weather hit in February, the center wasn’t ready, so St. Matthew stepped in and opened an emergency shelter.

“Washougal successfully demonstrated how rural communities can plan and implement a realistic solution to a community problem in an expedited manner,” Baker wrote. The Salvation Army at 1612 I St. hosted a grand opening for its expansion on Feb. 24. For about six months, the nonprofit has operated the facility, which features a shower, laundry room and food pantry. There is a room with clothes and household items for people to take, along with free breads and pastries. There’s space for people to just hang out. Volunteer Joyce Bjork said three people stayed all day on a recent Friday, using it as a kind of day center.

On Feb. 28, Washougal High School opened its Panther Den, a resource room where students can find clothing, hygiene products, school supplies and food. The room has business attire for students to use on loan for job interviews and senior project presentations, and a changing room for students to try on clothes to make sure they fit. Bob Barber, pastor at St. Matthew and chairman of Refuel Washougal, helped develop the Panther Den. The goal is to provide students, like Ortiz, with some basic items.

Ortiz said that while homeless and jumping between housing, his grades slipped to a point where he was a C-plus student. Since living in stable housing this year, while he’s a senior at Washougal High School, he’s been getting A’s. Ortiz is going to attend Central Washington University in the fall, where he’s considering studying to become a child psychologist to help out kids who are dealing with the same problems he’s faced.

He said he didn’t talk much about his living situation while he was homeless, except to a few friends in similar financial straits.

“It was not something talked about,” he said. “It’s not like people don’t care. They just don’t know the extent to which this is happening.”

Enlarge

(Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian)

Adam Littman: 360-735-4518; adam.littman@columbian.com; twitter.com/a_littman

Patty Hastings: 360-735-4513; twitter.com/pattyhastings; patty.hastings@columbian.com