The memories of teenagers who died by suicide are closely guarded by those left behind.

The smiles and laughter, the shared experiences, the first days at school and the last hours spent together are beacons for families of children whose lives were cut short after ongoing struggles with mental illnesses including depression, anxiety or eating disorders.

There’s Heidi Bucklin, who died at 18, a competitive athlete whose seriousness on the field afterward melted into goofy grins with her friends.

There’s Zayne Shomler, who died at 17. He loved little things — watching ants march back to their colony, his turtle and the tiny stuffed lamb he kept close even until his death.

There’s Heather Brooker-Higgins, who died at 13. She loved to learn so much, she would spend hours studying Spanish on her school-issued tablet.

These are some of the teenagers who have died by suicide in Clark County, as long ago as six years and as recently as two months. It’s a constant and apparently escalating problem.

While teen suicides appeared to stay steady in recent years — ranging from six in 2011 to nine in 2015, according to the state Department of Health — early data suggests deaths could be rising this year. As of July, the Clark County Medical Examiner reported seven teenage deaths this year where suicide was confirmed as the cause. And the incidence may even be greater.

The Trauma Intervention Program, a nonprofit organization that works with local law enforcement to send volunteers to the scene of traumatic events to support families, has responded to 30 apparent teen suicides in Clark County this year, some of which are still officially under investigation.

TIP Executive Director June Vining isn’t surprised to hear about an apparent sharp uptick in deaths.

“We need to give these kids hope and coping skills and validate their feelings instead of telling them ‘Don’t feel,’” Vining said. “Feelings aren’t right or wrong, they just are.”

But why this year? Pointing to reasons is a more difficult task. Some suggest media consumption, including depictions of suicide on social media and television, could be a factor. Matthew Butte, development director for the Children’s Center, a family mental health organization, acknowledges teenagers appear to be experiencing more trauma, higher rates of anxiety and more depression at younger ages.

But, he notes, recovery through early mental health intervention and support is the norm for most teenagers, and not the exception.

“That piece makes a life-saving difference” for most families, he said.

Here are three stories of parents whose children have died by suicide, and their journeys of grief and acceptance in the wake of their loss.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

Heidi Bucklin, 18

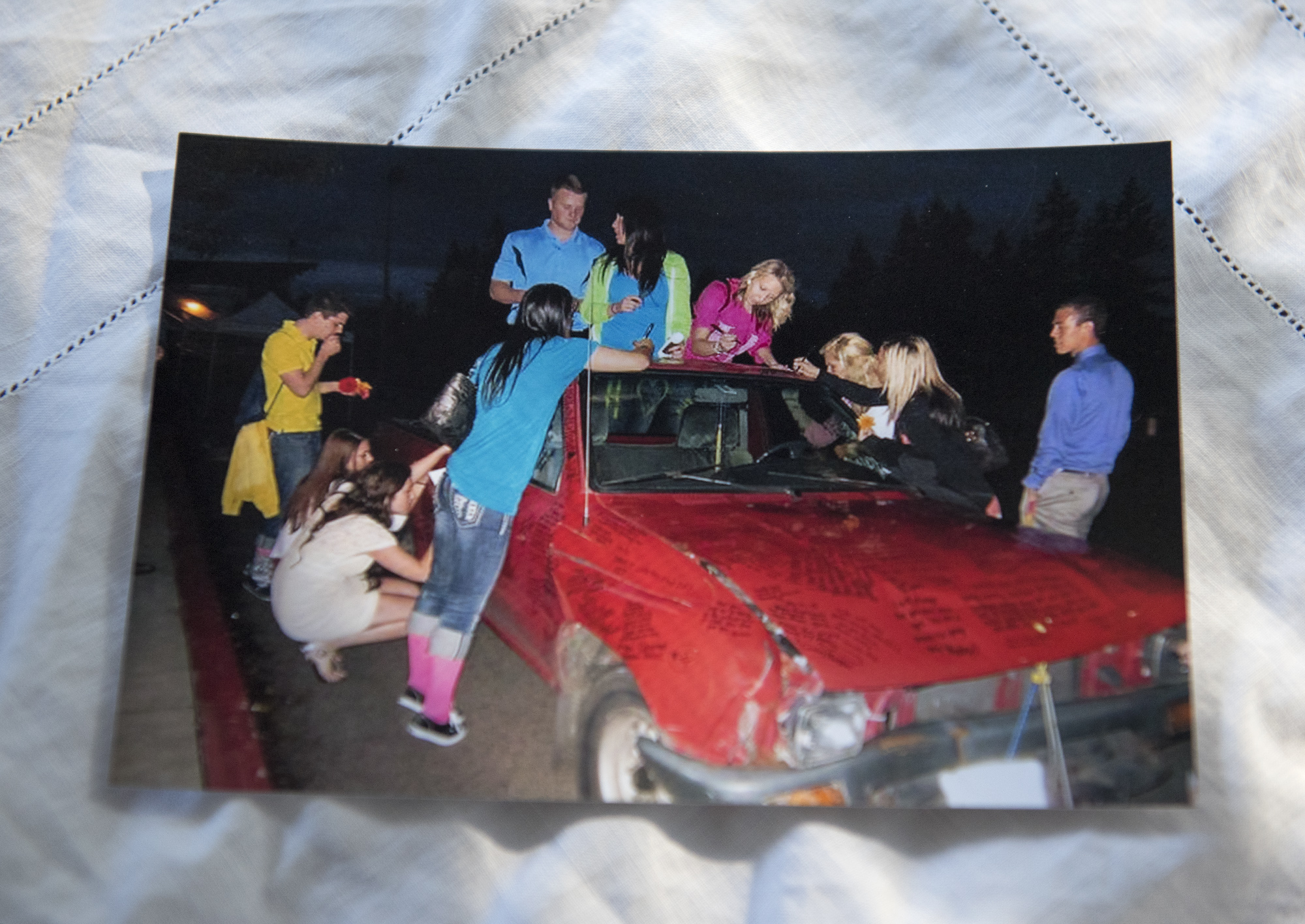

From a box of keepsakes, Ann Bucklin draws photo after photo of her daughter, Heidi.

In one, the 18-year-old high school senior flashes thumbs up as she sits in a box at Jamba Juice, where she worked. In another, she shows off brightly striped socks hiked up over her pants.

There’s one that makes Bucklin snort, where Heidi, dressed only in slippers and wrapped in a towel, picks out a Slurpee at 7-Eleven. Her friends had come to pick her up right after a shower, and the program “Teen Mom” was going to be on soon. There wasn’t time to get dressed.

“That’s who she was,” Bucklin said.

Heidi had 18 amazing years, Bucklin said. She had one terrible day.

May 23, 2011. The day Heidi took her own life.

Heidi was a senior at Columbia River High School. She loved to laugh. She loved competing in sports. She loved being with friends. She dreamed of working with disabled children, and would have attended Central Washington University. Her death shocked classmates and friends, who could not see the mental health challenges that lay behind her smiling face.

“It was really hard for people to comprehend,” Bucklin said.

But Heidi did struggle, Bucklin said. She had bulimia and anorexia, as well as anxiety, and had been hospitalized. She would hide her medicine in the potted plants at the breakfast table. Bucklin stopped working for a time so she could visit Heidi at school to make sure she ate lunch. Butte, with the Children’s Center, notes that one in five children have some kind of diagnosable mental health issue.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

“Here’s this kid who was happy and joyful and loves life,” Bucklin said. “But she still hurt. And she didn’t know what to do with it.”

There’s a sign hanging on Bucklin’s wall as visitors walk in that reads “Leave your mark.” It was a gift from one of Bucklin’s older daughters in memory of the one she lost.

“Leave your mark” is the mission statement for the locally owned Jamba Juice franchises. The message always resonated with Heidi, who loved her job. But she feared she hadn’t done enough to leave her mark, Bucklin said.

Yet in hundreds of letters written to Heidi, pulled from that box of memories, fellow students described their love for their friend, sharing goofy stories and times they’d laughed together. Some who barely knew her recalled times the bubbly teenager had talked to them when others wouldn’t. One friend wrote about the time Heidi dragged her into the rain and made her shout “I’m beautiful and I believe it” to the sky when her self-esteem was low.

In the aftermath of her daughter’s death, Bucklin is working to leave her own mark — and to ensure Heidi’s continues.

Bucklin is a regular visitor to forums and events on the subject of teen suicide, sharing her story of recovering from the loss of her own child. She volunteers for the Trauma Intervention Program, responding to crises, including suicides, to provide support for families. She organized a Facebook group for mothers who have lost children to suicide, “A Moms Heart,” and visits with those women for coffee or drinks when they need the comfort. She established a college scholarship fund in Heidi’s name through the sales of T-shirts and pink bracelets reading “Leave your mark,” giving $5,100 each to three students.

Two months after Heidi died, Bucklin organized a hike up Angel’s Rest in the Columbia River Gorge. The two-mile uphill hike bursts out into a rock outcropping with sweeping views of the Columbia River. There, Bucklin and a small group of Heidi’s friends scattered her ashes – which they’d carried in a Jamba Juice cup.

“I wanted something positive and healthy,” she said.

Bucklin does that hike at least once a year, on the anniversary of the day Heidi died and sometimes on other days when she feels the need. On a visit to Angel’s Rest last month, almost six years exactly since the first trip, Bucklin said it’s the time she lets herself think of what might have been. Would Heidi have thrived in college, away from the high school stress? Would she be working with children like she’d dreamed? Would she be married and starting a family of her own?

“It never gets easier,” Bucklin said of mourning her daughter. “It never gets better. It gets different.”

Zayne Shomler, 17

The center of 17-year-old Zayne Shomler’s life was his 50-gallon turtle tank, and the creatures that lived inside and nearby.

Clark, a red-eared slider, swims surrounded by goldfish, as Pajamas, Zayne’s cat, perches on the edge of the tank and watches.

This scene remains as the centerpiece of Gayla Shomler’s living room, but Zayne, her son, no longer sees it. The 17-year-old Skyview High School junior took his own life 1½ years ago after a private struggle.

Zayne was a smart, active child, Shomler said, and that continued into high school. He was a straight-A student, on the football team and involved in the school’s leadership class.

Enlarge

(Provided Photo)

“One of the things he did was write a personal note to every kid in the class telling them what was good about them,” Shomler said.

Shomler began to notice strange behavior in the months before Zayne died, though she never thought it could indicate a struggle with mental illness. Zayne had recently broken up with a girlfriend and his parents were separating, among other typical teenage stressors.

Once, when they were about to clean the turtle tank together, a regular ritual, he suggested giving the turtle away – a shock since he’d begged for a turtle for years.

“I said, ‘Zayne, no!’” Shomler said.

On another night, she found Zayne, asleep in bed with the light on, fully dressed from the day before.

Christina Padden, a nurse practitioner with The Vancouver Clinic who specializes in children’s mental health, noted that any changes in behavior can be a sign of depression or mental health issues.

“If they’re struggling more in school, seeming to withdraw, not being with friends, having risky behaviors, drugs or alcohol, expressing feeling sad, crying, feelings of guilt and worthlessness,” she said. “Those are all things that would indicate there might be something else going on.”

It’s safe to ask teenagers if they’re thinking of hurting themselves or killing themselves, she said.

“That does not make kids suicidal,” she said, adding that it’s too easy for teens to respond superficially if asked, “Are you OK?”

The day Zayne died — Feb. 8, 2016 — he left behind a note suggesting his struggles with mental illness were rooted far deeper than his mother realized. He described having suicidal inclinations since he was in fifth grade, and pointed to questions about his own identity that she had been otherwise unaware of.

“It was really very, very shocking that he did what he did,” Shomler said.

Shomler wondered what she could have done differently, what signs she could have noticed that might have saved Zayne’s life. But in her conversations with other people who lost loved ones to suicide, she realized his death was not her fault.

“Even if I had been more aware, would it have changed things? I don’t know,” she said. “I don’t want to give the message that there’s no hope, that you can’t change anything because certainly there are lots of kids that if you see it, there are things you can do. There’s no guarantee, and it’s not your fault if they make that choice.”

Earlier this year, Shomler tried to organize a party in honor of what would have been Zayne’s graduation. She shared a photo of his graduation cap, complete with a turtle charm, on Facebook.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

But how do you gather families celebrating their own children’s accomplishment to honor what could have been? She never managed to organize a party, but a few days after graduation, the Shomler family had the celebration they needed: a family game night around Zayne’s favorite board game, Settlers of Catan.

“I’d get these one-word texts from Zayne. ‘Catan?’” she said. “That was a signal we were going to have a family evening playing Catan.”

Zayne was tough when he played, and nearly always won. Shomler feared what might happen if she won in Zayne’s absence. It would be a reminder that he was missing.

“There was a time when I couldn’t conceive of ever playing it again,” she said. “It was just too much.”

But as Shomler’s oldest son prepared to move to California, and in the aftermath of graduation, her youngest asked if it was time for a family game night. Sure, Shomler said, finally ready after more than a year away from the game Zayne loved.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

They created the “Zayne Rule” in his honor, she wrote on Facebook: Play as cutthroat as you want, but remember, it’s just a game. Just like he played.

“Eventually it kind of settles into, yes he’s missing in a physical sense, but he’s never gone,” she said. “It brings him close to play the game.”

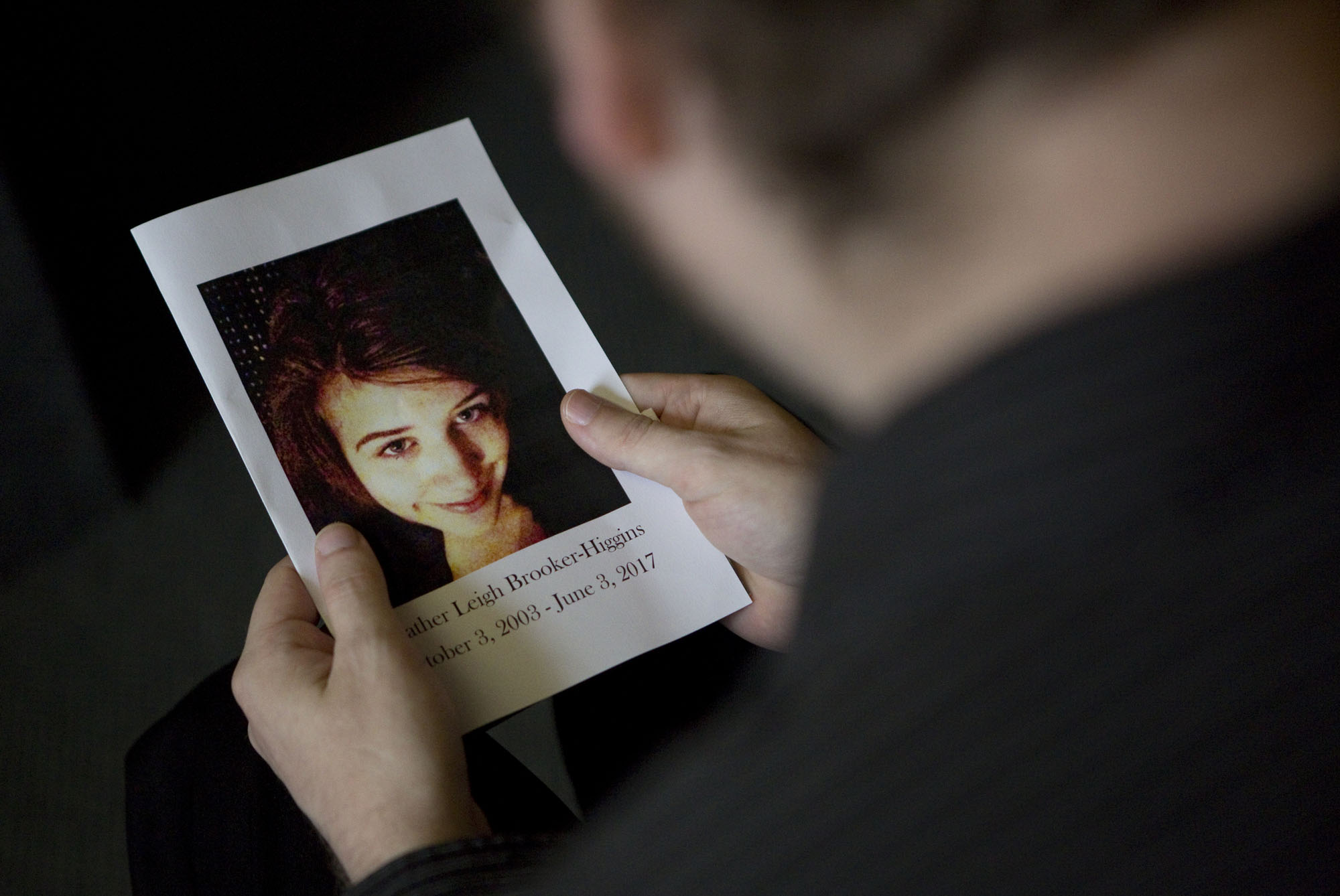

Heather Brooker-Higgins, 13

Butterfly stickers adorn nearly every surface of Vickie Higgins’ and Eric Franklin’s apartment, an homage to one of 13-year-old Heather Brooker-Higgins’ favorite creatures. Flowers and sympathy cards cover tables. Heather’s drawings burst from shelves.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

“There’s so many things I would like to say to Heather,” Higgins said, looking around the room as she grasped for words. “I want to give her a big hug and never want to let her go.”

Heather died a little more than two months ago, on June 3. Her mother and stepfather are still in the immediate aftermath of trying to make sense of the loss of their child. Most of the flowers and cards scattered are from Heather’s memorial service, and the family is in the process of going through her belongings as they prepare to move to a new home.

Enlarge

Alisha Jucevic/The Columbian

“We see it every day,” Franklin said. “The missing chair. The empty spot in our lives.”

Heather had anxiety and was bullied at school, her parents said. She was receiving counseling and medication, but began showing signs of suicidal inclinations earlier this year.

Higgins and Franklin said they struggled to get the professional help Heather needed. Counseling appointments required weeks of waiting. After a suicide attempt earlier this year, Heather graduated from a mental health treatment program. She was better for a time, then appeared to slip back into depression.

Padden, with The Vancouver Clinic, acknowledged that the wait for services can be long.

“I think there’s more awareness and less stigma,” she said of mental illness. “I think that is getting better so more people are seeking help, which is good, but we need to keep up with the demand.”

At Heather’s memorial service, former teachers described the Gaiser Middle School student as a curious soul who loved to be challenged. She’d pore over her Spanish-language learning application on her iPad, excitedly sharing with her stepfather her progress and planning conversations with her Hispanic relatives. She was many new students’ first friend, teachers and her family alike said, welcoming them and showing them around campus. She volunteered at the child care center at Walnut Grove Church, and her eyes would light up every time she taught a child something new.

“It gave her a sense of purpose,” Franklin said.

Since she died, the stories have been overwhelming.

“You just don’t realize how many people that your child touches,” Franklin said. “How many hearts and doors and lives that they’ve opened by having that child in theirs. When that flood of support comes it is overwhelming. Not to mention you’re already in a critical time. You’re already a heaping mess. But it helps to make a little bit of sense of it.”

In the wake of Heather’s death, the couple have drawn strength from each other. Higgins is taking time away from work, and the pair are trying to take their younger daughter on more outings while they have the time together.

“We have to stay strong,” Franklin said.

He paused.

“There were a lot of good times,” he said.

The family is raising money to cover moving expenses and other costs associated with Heather’s death. Visit gf.me/u/bk4th4 to donate.

Behind the story: Families, friends illustrate suicide’s devastation

A few weeks ago, I arrived at my desk to see my phone voicemail blinking.

It’s an anxiety-inducing sight for any reporter. Was there something wrong in a story?

The message, as it turns out, hit me even harder: A caller, who didn’t leave a name, demanding to know why I wasn’t writing about teenage suicide.

The depth of this issue wasn’t clear to me until I saw state Department of Health data showing suicide rates for people 19 and younger were fairly steady from 2011 to 2015, followed by a call to June Vining, director of the Trauma Intervention Program of Portland/Vancouver. Vining shared that 30 teenagers, at latest count, have apparently died by suicide already this year.

If you need help

There are counselors and organizations in Clark County that focus on childhood and family mental illness. The Children’s Center provides mental health support for families and contracts with the Battle Ground, Evergreen, La Center and Vancouver school districts to provide services on campuses.

“We’d like to see more access to care, making it as easy as possible, removing some of those barriers and being where (children are),” Development Director Matthew Butte said.

Christina Padden, a mental health nurse practitioner at The Vancouver Clinic, advised parents who have children with a mental illness to seek counseling for themselves as well as their children. “This isn’t something that parents should deal with on their own,” Padden said. “Definitely come in and seek help if you need it. It can be hard to navigate the system, but there are lots of good therapists out there and people out there to help.”

If you are having suicidal thoughts, the following hotlines are available for confidential support.

• Southwest Washington Crisis Line: 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. 1-800-626-8137

• The Trevor Project Lifeline for LGBTQ young people: 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. 1-866-488-7386

• Teen Talk for Clark County youth: 4 to 9 p.m. Monday through Thursday, 4 to 7 p.m. Friday. 360-397-2428

• National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

In the process of writing about local reactions to “13 Reasons Why,” a Netflix drama detailing a high school girl’s struggle with mental illness followed by her suicide, I met Ann Bucklin. Bucklin, whose daughter Heidi died in 2011, and I had met at two youth suicide community forums. She shared her story briefly with me, then emailed me in June.

“I wanted to offer up my experience … if you were interested on what happens after a suicide to family and friends,” she said.

Bucklin didn’t know it at the time, but her story is exactly what I was looking for — a story that would illustrate the devastation a family suffers after losing a child to suicide.

It was from there the pieces began to fit together. Just days later, I received another phone call from a friend of Vickie Higgins, whose daughter, Heather Brooker-Higgins, died about two months ago. She asked if I could help share their story, and helped put me in touch with Higgins and her partner, Eric Franklin.

Bucklin, who manages a Facebook group for mothers of people who have died by suicide, “A Moms Heart,” connected us with Gayla Shomler, whose son Zayne died last year.

I was stunned and humbled by the openness and frankness of all three families, who spent hours visiting with myself and two of our photographers, Ariane Kunze and Alisha Jucevic. We wanted to tell the story in writing, photos and video of these families — the happy memories, the things that made their children who they were, the bits of joy these families pull from in times of sorrow — coupled with input from mental health providers about how mental illness manifests in teenagers.

You’ll notice a couple things in this story. We do not detail the way these children died. Bucklin said people jump to ask her that question when she tells them her daughter died by suicide. She put it best when she said it feeds a “morbid curiosity.” That information benefits no one, and we wanted to reduce the possibility this story might contribute to suicide contagion.

Also, we never say these children “committed suicide.” That language hearkens back to the time suicide was considered a criminal action and not a function of mental illness. People commit a robbery, commit fraud and commit a murder. They die from cancer, die in an accident, die from old age. They die, in some circumstances, by suicide.

I’d like, again, to iterate my gratefulness to Higgins and Franklin; Bucklin and her friends and family; and Shomler and her surviving sons for welcoming us into their homes and lives to share the stories of their children. We hope these stories help families who may be worried for their children and don’t know where to turn.

And, for that reader who called to point out my failure at not writing about this sooner: Thank you for lighting the fire.

Story by Katie Gillespie: katie.gillespie@columbian.com

Photos by Alisha Jucevic: alisha.jucevic@columbian.com

Video by Ariane Kunze: ariane.kunze@columbian.com