RIDGEFIELD — The music is loud, filling the back bedroom and seeping into the otherwise quiet house. Jordan Jhaveri, 17, sits in front of the computer, searching for a song to play. She settles on a new Selena Gomez song. Then, she turns to her dad.

“You don’t like this song?” she asks.

Akhil blinks his eyes once — his signal for “no.”

“Too bad,” Jordan shoots back with a smile. “Learn to.”

Akhil smiles. Music has always been a way for him to connect with his daughters.

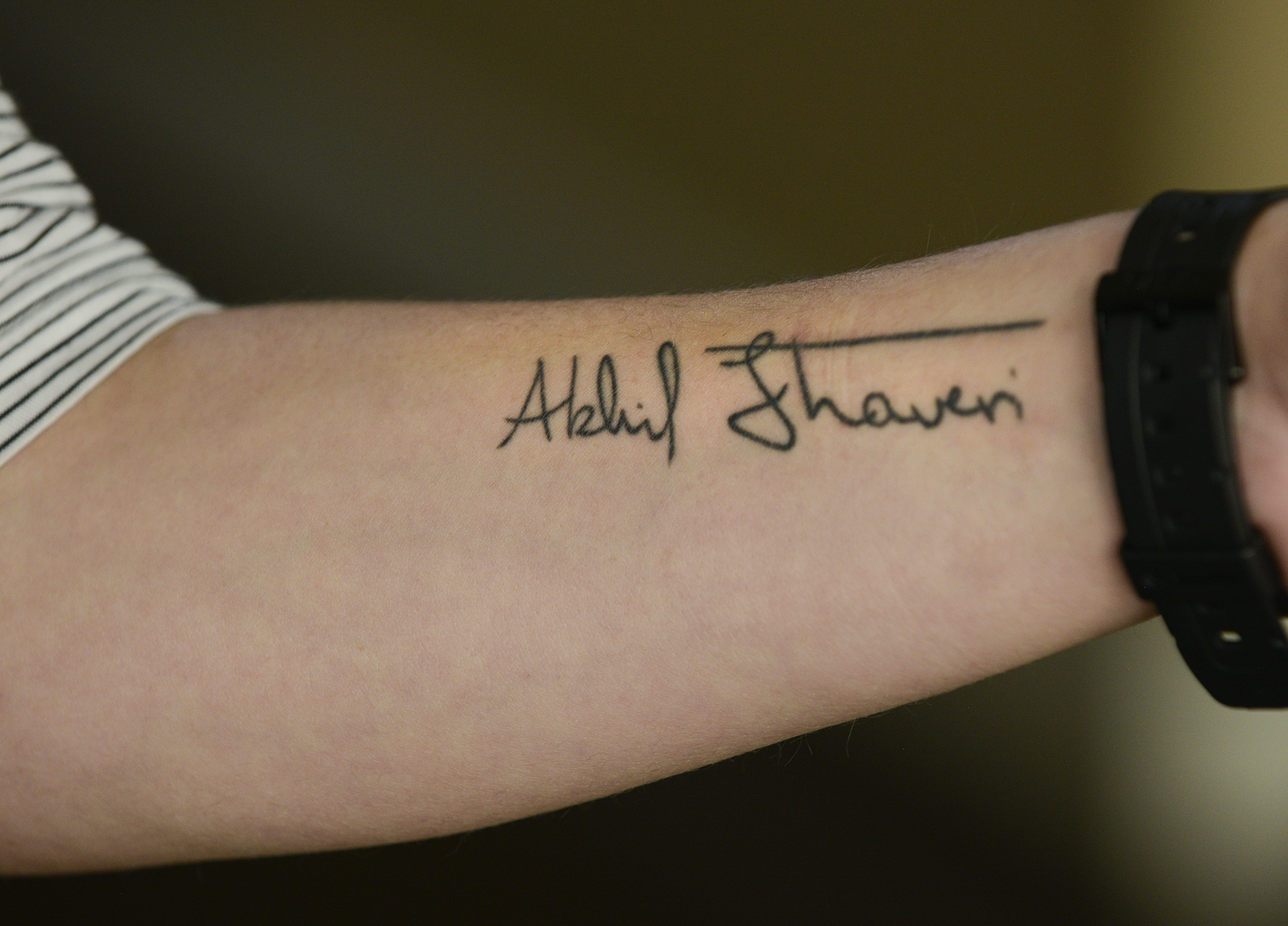

Akhil’s oldest, Ashley, 23, takes over at the computer. She picks a cover of a Taylor Swift song. She plops down on the hospital bed in her parents’ bedroom and begins to roll up the sleeves of the flannel shirt she took from her dad’s closet.

For the better part of an hour, the girls take turns choosing music and telling each other about things happening in their lives. They sing at the top of their lungs. They dance around the room.

All the while, Akhil sits in his wheelchair and watches. He smiles when the girls belt out the lyrics to “Bohemian Rhapsody.” He tears up when they play his favorite song, “Come Sail Away,” by Styx.

Speaking is impossible and communicating via his computer is tedious. So, for the most part, Akhil is quiet in the lively room.

When the girls turn off the music and prepare to head their separate ways, Akhil has a request. He uses his eyes to spell out the words on his computer and uses a trigger next to his leg to direct the computer to read the words out loud.

“Suction, please.”

No cure

Akhil, 51, was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in July 2011. ALS, commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. The disease causes nerve cells to gradually break down and die, leading people with ALS to lose the ability to control the muscles needed to move, speak, eat and breathe.

There is no cure. For most people, the disease is fatal within two to four years of the diagnosis.

In November 2015, The Columbian produced “A Strong Man,” a three-day series of stories, photos and videos about Akhil Jhaveri and his family as they navigate life with ALS.

At first, Akhil seemed OK physically. He would stumble from time to time, and his speech would sometimes be slurred. But, slowly, the disease progressed and the list of tasks Akhil needed help with grew longer and longer.

Akhil has lost the ability to move his limbs. His neck strength has dwindled, making it difficult for him to lift his head. His breathing has become more shallow and labored, particularly in the last year or so, and he’s constantly battling an overproduction of saliva that requires regular suctioning.

As his condition declined, Akhil managed to hold on to his ability to communicate. He spoke in fragmented, breathless sentences that were difficult for those who weren’t around him often to understand, but he could communicate.

Now, ALS has taken that, too.

Akhil relies almost entirely on his computer to communicate. His wife, Laura, and daughters can sometimes anticipate his needs and ask yes or no questions to pinpoint what he wants. Akhil blinks once for “no,” raises his eyebrows for “yes.”

Laura and Akhil have also memorized a chart of letters they can use to spell out words. Laura calls out row numbers — one through six — and each row has a corresponding set of letters. Akhil raises his eyebrows when Laura calls out the row he wants. She rattles off the letters of the alphabet in that row until Akhil signals she’s hit the right letter. Then, they move on to the next letter in the word.

“I equate it to how a person with one leg would fare in an ass-kicking contest.” Akhil Jhaveri

Spelling out words takes time, but it works well for times when the computer isn’t set up.

For Akhil, losing the ability to communicate means he’s gone from participating in conversations to observing.

“I equate it to how a person with one leg would fare in an ass-kicking contest,” Akhil said via his computer. “I try, but it is frustrating because by the time I respond, everyone has moved on to another topic and everything I’ve painstakingly typed is irrelevant.”

“The one-legged man and I are tired of trying to keep up,” he added. “So, we’ve resigned ourselves to being spectators.”

That’s not lost on any of the Jhaveri women.

“I can still tell him stories about me and my day and what makes me think of him, and it’s great because you can still see his face light up. But when it comes to hearing some witty banter back, that’s the one thing,” said daughter Corinne, 21, her voice trailing off.

Physically, the labored breathing and difficulty swallowing has made life more uncomfortable for Akhil. In addition to struggling to breathe, the buildup of saliva in his mouth and throat can, at times, make Akhil feel like he’s going to choke.

Ariane Kunze

And as Akhil’s digestive system slows down, he has a harder time tolerating formula and water without feeling bloated. And, Laura said, it’s important not to force it because the fluid could back up and cause Akhil to aspirate, drawing the liquid into his lungs. In most cases, the terminal aspect of ALS is tied to respiratory issues.

Jordan — a junior at Ridgefield High School who spends her days in the Running Start program at Clark College — is the only of Akhil and Laura’s three daughters who lives at home. She’s seen her dad’s decline firsthand. But, for that reason, she doesn’t notice the gradual changes, just realizes that things are different.

For Ashley, who recently graduated from Eastern Washington University and lives in Spokane, the decline is more obvious.

“Every time I leave, there’s a forgetting period,” Ashley said. “I always know my dad is sick, but I don’t think about it if I don’t have to.”

“So it’s always kind of jarring to see him because it’s like, ‘Oh, I forgot how bad it was,’ ” she said. “Every time I come home, it’s a new reminder of what’s going on.”

Time squeeze

In the last year, Laura has resumed her role as Akhil’s primary caregiver. Before, Akhil had a full-time caregiver who stayed overnight five days a week. Laura still has help from a couple of paid caregivers, but they only spend weekday mornings with Akhil. That allows Laura, 51, to have about 3½ hours each day to take care of errands and other work outside of the house.

Most often, that time is devoted to activities related to her expanding dessert business, Killa Bites.

“It’s a challenge to live my whole life outside of these walls within those hours,” Laura said.

Despite the stress and the often hectic days, Laura charges on.

“It’s important my girls see me stick it out and love their father the best I can,” Laura said. “I never, ever wish that he weren’t here. People may find that hard to believe because it’s a lot of work … but there’s not a moment I wish he weren’t here.”

Enlarge

Ariane Kunze

That’s not to say some days aren’t harder than others. Not only is the disease isolating for Akhil, it’s a source of loneliness for Laura. And the daily reminders of the life she once shared with her husband — and the dreams she had for their future — can be tough to face. Something as simple as walking into the closet in their bedroom can flood Laura with memories, with reminders of how things once were.

She can picture her husband wearing his favorite outfit, bouncing out of the closet to take her on a date. She can see him wearing a button-up shirt and tie, heading out for a day at the office. She can imagine him dressing up in a suit, ready for an evening out.

“I still cling to that hope that maybe he will, maybe there will be some breakthrough that helps people with ALS.” Laura Jhaveri

But the reality is Akhil hasn’t even worn pants in the last six months. As his ability to help move his body deteriorated, Laura found it too difficult to manipulate his limp body into pants. Instead, a sheet is draped over his lap.

So when it came time to start spring cleaning, Laura decided to tackle the walk-in closet. She wasn’t prepared for how difficult the simple task would be.

“I felt like I was conceding something to ALS,” she said. “I felt like when I got rid of some of his clothes, I was saying goodbye to a piece of Akhil.”

Realistically, Laura admits, she could have gotten rid of all of Akhil’s pants with zippers and shirts with buttons. He will probably never wear those again. But she couldn’t bring herself to do it.

“I still cling to that hope that maybe he will, maybe there will be some breakthrough that helps people with ALS,” Laura said. “Clinging to that hope is one of those things that allows me to get through yet another day dealing with this.”

For Akhil, knowing that he’s still making a difference in people’s lives — that he’s inspiring others and touching their lives in some way — is enough to keep him going.

“When I received the diagnosis, I just kept living,” Akhil said. “As things progress, I do the same thing. I just keep living.”

“As long as I get love and give love, life is good.”

Marissa Harshman: 360-735-4546; marissa.harshman@columbian.com; twitter.com/MarissaHarshman